The Mafia’s history in Las Vegas: From Bugsy Siegel to Anthony Spilotro

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel had been at the helm of the Flamingo for only six months in June 1947 when he was killed in a hail of gunfire at his girlfriend’s Beverly Hills, Calif., home.

But his vision for the Flamingo, the first resort-style hotel on the Strip, was the beginning of a 50-year relationship between Las Vegas and traditional organized crime that helped define “Sin City”and turn it into one of the world’s top tourist destinations.

“The general perception on the part of the public is that Las Vegas and the mob have been inextricably linked, and I don’t think it will ever be extricated,” former longtime state archivist Guy Rocha says.

Groundbreaking books such as “The Green Felt Jungle” in 1963, which revealed the mob’s early grip on the city, and popular movies such as “The Godfather” in 1972 and “Casino” in 1995 enhanced this perception through the years.

So did the buzz on the Strip over the Rat Pack, led by headliner Frank Sinatra and his associations with high-profile underworld figures.

In reality, Las Vegas was regarded as an “open city” for more than two dozen Mafia families across the country. Many had representatives in Las Vegas for decades, with Chicago being the most dominant.

The colorful mob era has long since passed, but Rocha believes it should not be forgotten.

“We owe a debt of gratitude to the Mafia for developing Las Vegas, and there’s nothing to be ashamed of,” Rocha said. “It was the mob that moved (Las Vegas) forward, with the good, the bad and the ugly.”

Siegel, a hit man and trusted associate of Charles “Lucky” Luciano, who organized the Mafia from New York into a national crime syndicate, had financed the Flamingo with the help of the mob’s money man, Meyer Lansky.

Kefauver comes to Las Vegas

Historians believe the flamboyant Siegel may have been killed because he was stealing money from the casino operations. Journalistic photos of his bloodied, bullet-riddled body lying in the Beverly Hills home are a stark reminder of what can happen when the mob is crossed.

Lansky brought in new underworld associates to run the Flamingo after Siegel’s death, and the resort became the model for a string of mob-backed joints, including the Thunderbird and Desert Inn, that later sprang up on the Strip.

“You might say it was a perfect storm in a good way for Las Vegas,” says Michael Green, a College of Southern Nevada history professor who has been chronicling the mob’s presence in Las Vegas. “There were people running casinos who weren’t in the mob but didn’t have the money to expand, and there were people in the mob who had the money but didn’t know how to run a casino.”

It didn’t take long for the mob’s involvement in Las Vegas casinos to catch the attention of U.S. Sen. Estes Kefauver, a politically ambitious Democrat from Tennessee who was holding hearings across the country on organized crime.

Kefauver brought his committee to Las Vegas for a Nov. 15, 1950, hearing at the old federal building downtown, now the site of the National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement, better known as The Mob Museum.

Green, an advisory council member and researcher for the museum, said Las Vegas was proof to Kefauver and other anti-mob crusaders that organized crime was bad and shouldn’t be running a big business.

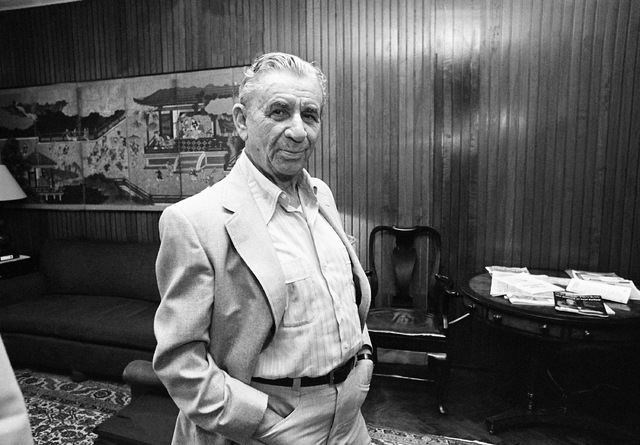

One of the mob-connected figures the Kefauver committee wanted to question under oath was Moe Dalitz, an old-time bootlegger and racketeer from Cleveland who had led the group of investors that developed the Desert Inn.

Dalitz, who had strong ties to Lansky, managed to duck the committee, but later wound up testifying in Detroit, where he also had business interests.

The televised Kefauver hearings forever tied Las Vegas to the mob in the eyes of the American public and inspired reforms and organized crime prosecutions elsewhere in the country, Green said.

But it did not slow the growth of gambling in Nevada, the only state where it was legal, and the mob’s influence in Las Vegas.

Gambling lifeblood of organized crime

The 1950s brought the onslaught of more mob-connected casinos on the Strip — the Sands, Dunes, Riviera, Tropicana and Stardust.

Several were financed or refinanced with millions of dollars in loans from the mob-dominated Teamsters Central States Pension Fund.

Dalitz, who was close to Teamsters Union President Jimmy Hoffa at the time, played an instrumental role in helping secure some of these loans and would become a pillar of Las Vegas society until his death in 1989, even once being named humanitarian of the year for his many philanthropic contributions. Dalitz cemented his ties to the community by building Sunrise Hospital and the Desert Inn Country Club. Hoffa’s disappearance in 1975 remains one of the country’s biggest mysteries.

By 1960, with the mob’s rise on the Strip, state gaming regulators created the notorious List of Excluded Persons, more commonly known as the Black Book of “undesirables” banned from casinos, to keep a closer eye on the mob. In the first wave of inductees, regulators placed the names of 11 underworld figures, including then-Chicago Mafia boss Sam Giancana and Kansas City crime lords Nick and Carl Civella, into the book.

Months later after President John F. Kennedy was elected, his younger brother Attorney General Robert Kennedy went on a crusade against the mob nationwide and sought to rid Las Vegas casinos of its influence.

“Bobby Kennedy believed gambling was the lifeblood of organized crime, so to throttle organized crime he wanted to go after the casinos,” said David Schwartz, director of UNLV’s Gaming Research Center.

According to Green, the attorney general wanted to deputize a slew of state gaming agents to allow them to participate in massive Justice Department raids on the Strip.

Fearing a public relations nightmare for the state, then-Gov. Grant Sawyer persuaded the Kennedys to hold off on the raid, but the attorney general proceeded with his crackdown, which included secret wiretapping at casinos.

Little came of Kennedy’s anti-mob campaign, and the casino industry continued to grow with financing from the Teamsters pension fund. Caesars Palace opened with Teamsters money in 1966 under the tutelage of casino visionary Jay Sarno. Two years later, Sarno opened Circus Circus.

“It basically was a flawed law enforcement strategy,” Schwartz said. “They thought they would get people to flip, but as it turned out, people were more afraid of the mob bosses than they were of the Justice Department.”

Enter Anthony Spilotro

In the late 1960s, billionaire recluse Howard Hughes did what Kennedy was unable to. Hughes changed the face of gaming when he bought the Desert Inn from its mob-connected owners and several other casinos on the Strip.

Hughes’ foray into Las Vegas led to corporate America’s push to take control of the casino industry from the mob.

By 1969, the Nevada Legislature passed a law easing the way for corporations to own casinos, and a year later, Congress passed the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, giving the Justice Department more ammunition to fight the close-knit crime syndicates.

“The RICO Act made it easier to go after the mob, and the Justice Department put more effort into going after them,” Green said.

For the first time, the Justice Department was allowed to use criminal statutes to investigate Mafia families as ongoing criminal enterprises. Organized crime strike forces were created in major American cities, including Las Vegas, to focus solely on the mob’s activities.

But organized crime was far from losing its foothold on the city.

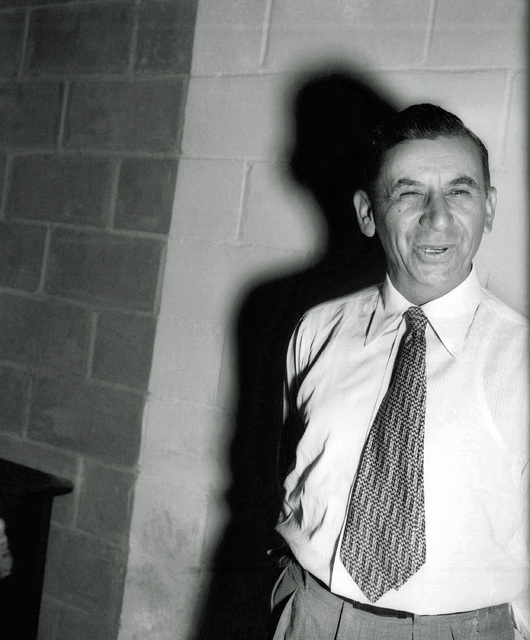

In 1971, the Chicago mob sent Anthony Spilotro to Las Vegas to take over loan-sharking and other street rackets from Marshall Caifano, one of the 11 original Black Book members.

Spilotro was also instructed to keep an eye on Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, a vocal longtime oddsmaker who was in charge of the crime family’s skimming operations at the Stardust and Fremont casinos. Money was being taken directly from count rooms and sent back by courier to mob bosses in Chicago, Kansas City, Milwaukee and Cleveland, right under the noses of Nevada gaming regulators.

The crime syndicates installed San Diego businessman Allen R. Glick at the helm of the Stardust and Fremont as a licensed frontman who secretly answered to Rosenthal and Spilotro. At the Tropicana, Joseph Agosto was given the job of entertainment director to quietly oversee skimming for the Kansas City mob.

Breaking mob’s hold

Spilotro, a “made member” who rose through the Chicago mob’s ranks as an enforcer and hitman, ran his Las Vegas rackets from the gift shop of Circus Circus until authorities forced him out.

From there, he moved to the Gold Rush jewelry store on West Sahara Avenue near the Strip, where he became adept at fencing stolen jewelry with one of his top lieutenants and childhood chum, Herbie “Fat Herbie” Blitzstein.

Spilotro also ran a burglary ring, later dubbed the “Hole in the Wall Gang,” because of its practice of drilling holes through the walls and ceilings of the buildings it entered.

For years, Spilotro managed to stay out of prison, both in Las Vegas and Chicago, with the help of his loyal criminal defense lawyer, Oscar Goodman, who courted media relationships and became the outspoken “mouthpiece” for Spilotro and other mob figures in an ongoing war of words with lawmen.

But by 1981, federal authorities began making headway in their intensive investigation of Spilotro, the Chicago mob and other Midwest crime families suspected of skimming money from casinos.

Spilotro’s fencing operation had been broken up, and key members of the Hole in the Wall Gang were arrested by Las Vegas police in an undercover burglary sting at Bertha’s gift shop, then on West Sahara Avenue.

Months later, Frank Cullotta, a childhood Spilotro friend who was arrested with five others in the burglary, decided out of fear for his own life to cooperate with Las Vegas police and FBI agents.

Cullotta’s cooperation marked the decline of Spilotro’s reign on the streets.

In June 1986, as federal authorities kept up the pressure, the battered and bloodied bodies of Spilotro and his younger brother, Michael, were found buried in an Indiana cornfield. Years later, their killers, who acted under orders from mob bosses, would be convicted in Chicago.

By the time of Spilotro’s slaying, federal authorities had convicted a string of Midwest Mafia bosses for skimming money at the Stardust, Fremont and Tropicana casinos. Other mob figures had been convicted in Detroit and Las Vegas of wielding hidden influence at the Aladdin.

The mob had lost its grip on the Strip, and its control over street rackets diminished.

New Organized Crime

Federal and local authorities kept an eye on traditional organized crime in the 1990s, but it did not rise to the level of previous decades.

In 1997, Blitzstein was murdered in a plot by Buffalo and Los Angeles mobsters to take over his loan-sharking operation.

At the time, although not on the day of his death, FBI agents had been conducting surveillance of Blitzstein and other mobsters in what was regarded as the last big racketeering investigation of the Mafia in Las Vegas.

Two years after Blitzstein’s death, Goodman took a new career path and was elected mayor of Las Vegas, where he held office for 12 years. During his tenure, he pushed for the creation of The Mob Museum.

After Cullotta got out of federal prison and witness protection, he did his part to keep alive memories of organized crime in Las Vegas. He started a business that provided tours around town of old mob haunts.

Law enforcement authorities also changed their priorities.

They have taken notice of less colorful but more sophisticated organized criminal groups — those with roots in Asia adept at pulling off casino cheating and marker schemes, and those from Russia and Eastern Europe knowledgeable about financial fraud, credit card and cyberschemes.

Las Vegas and organized crime, it turns out, are still inseparable.

Green puts it in terms Bugsy Siegel would appreciate:

“Traditional organized crime may be gone, but there will always be organized crime of some kind here, as long as we have gambling and there’s money to be made from it.”

This story originally published on March 9, 2014. It has since been updated.

Contact Jeff German at jgerman@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4564. Follow @JGermanRJ on Twitter.