The last scene of his life unfolds in 12 grainy seconds.

Tupac Shakur’s swinging hard in the final footage captured of him alive.

It’s 8:49 p.m. on Sept. 7, 1996.

Heavyweight champ Mike Tyson has just broken down Bruce Seldon without breaking a sweat at the MGM Grand, dispatching his foe in 109 seconds, ending things with a left hook unleashed like a tiger from a cage.

Shakur’s hyped after the bout.

“Twenty blows! Twenty blows!” associates recall him exclaiming upon Tyson’s destruction of Seldon in under two dozen punches.

As he’s walking back through the hotel, Shakur spots Orlando Anderson, a known gang member who got into it with a member of Shakur’s Death Row Records crew, Travon “Tray” Lane, that year at a mall in Anderson’s native Los Angeles.

Shakur pounces.

He instigates a brief but brutal brawl in the hotel lobby that leaves Anderson flat on his back, absorbing kicks and the casino carpet at once.

Security cameras capture the scene, following Shakur departing the property in an adrenalized, get-the-hell-out-my-way strut.

And that’s the last we ever see of him alive.

Two hours later, Shakur is gunned down in his black BMW as it idles at a red light on Flamingo Road and Koval Lane.

Four .40 caliber bullets: two in the chest, one in the thigh, one in the arm.

They’d end the life of a legend.

Six days after the shooting, Tupac Shakur died.

He was 25.

Two and a half decades later, no one has ever been arrested for his killing.

The case remains unsolved, cold as the act of murdering a man.

Why?

“It depends on who you talk to,” says Stephanie Frederic, a journalist and film producer who’s worked on the Shakur biopic “All Eyez on Me” and the A&E documentary series “Who Killed Tupac?” “If you ask the Las Vegas police department, they’ll tell you it’s because, ‘Well, the people who know aren’t talking.’ When you talk to the people who do know, they’re like, ‘Oh, that situation is handled.’

“There’s too many dirty details,” she continues, “too many people who will come under fire, too many secrets that will probably get out, that shouldn’t be out. There’s so many entanglements.”

Tupac’s murder has spawned a smorgasbord of conspiracy theories, his death catalyzing a cottage industry of books, documentaries, even a big-time Hollywood film starring Johnny Depp, “City of Lies,” released in April.

Eaalirer this month, the Mob Museum weighed in with a new program, “One Night in Las Vegas: The 25th Anniversary of the Tupac Shakur Murder.”

The event examined Tupac’s murder and his enduring cultural legacy, with panelists Frederic, Public Enemy frontman Chuck D, Frederick Reynolds, a former police officer who assisted in investigating the many gang-related shootings and murders in Compton in the aftermath of Shakur’s death, and rapper E.D.I. Mean, a childhood friend of Tupac who was in the Shakur-formed hip-hop group the Outlawz and who was traveling in the car behind Shakur’s on the night of the shooting.

‘What? He’s gone?’

His voice conveys the same urgency as the sirens blaring in the background.

“I got a couple guys shot!” a Metro police officer shouts, speaking over the sound of a helicopter whirring nearby.

In audio recordings of police radio traffic on the night of the shooting obtained by the Review-Journal, you can hear the chaos unfold as various officers arrive on the scene.

“I need extra units up here now; extra units now!”

“We need medical to expedite. We need medical to expedite!”

“We’re taking people into custody.”

“Someone’s asking for help extricating the victim from the car. We need either a crowbar or something.”

Gold chains around his neck slathered in blood, Shakur is rushed to University Medical Center.

Suddenly, Las Vegas becomes posited at the center of national and international news cycles.

“Even though this incident occurred before social media and really before the internet became a thing, the news still spread incredibly fast,” recalls Schumacher, a longtime journalist who was the city editor at the Las Vegas Sun when Shakur was shot. “People were flocking to Las Vegas to somehow be a part of this.”

Frederic was among them.

A former West Coast correspondent for BET, she’d chronicled Shakur’s rise to stardom and had recently been on the set with him during the filming of his video for “I Ain’t Mad at Ya,” in which Shakur is forebodingly shot and killed.

When she got the call at her L.A. home that Shakur had been attacked, she immediately got on a plane to Vegas.

Frederic basically camped out at the hospital, watching as celebrities and community figures from Jesse Jackson to MC Hammer came to visit Shakur.

“It was chaotic. It was emotional. People kept saying to me, ‘He’s been shot before; he’ll be OK.’ But there was something about it that just seemed different,” she recalls.

“People would drive by and blow their horns or drive by with one of Tupac’s songs blasting from their car radio. It was intense,” she continues. “And you knew that this time was different because of the looks on the faces of the people when they would walk out of the hospital. I watched them come and go, and you saw the worried looks on their faces. You just knew that this time was different.”

Still, there was hope.

On the Thursday after the shooting, talk began to circulate that, although Shakur had allegedly lost a lung, he was recovering from multiple surgeries.

“We all sort of got word that everything was going to be OK,” Frederic recalls, “that he just may pull through this — another one — but life was going to be different for him.”

The very next day, Tupac Shakur was removed from life support by his mother, Afeni Shakur.

“We were like, ‘What?’ ” Frederic remembers. “I think we were all just shocked. ‘What? He’s gone?’ ”

A deafening code of silence

It wasn’t for a lack of witnesses.

Fourteen shots were fired — and at least that many eyeballs saw it all go down.

The Death Row Records crew rolled deep.

Including the night of Tupac’s shooting, when the BMW he was traveling in with Death Row Records founder Suge Knight was part of a group of vehicles full of his posse — save for the right-hand lane, where a white Cadillac would pull up and open fire.

“Remember, there was a caravan of cars at Koval and Flamingo,” Frederic says. “There was Suge and Tupac in that BMW, there was a Death Row guy in front, to the left — immediate left, upper left — and there were cars behind him — all that Death Row entourage. So you better believe they saw that car come up and the gun come out.”

And yet, no one talked then.

And no one’s talking now.

“To this day, none of those guys will tell you what happened,” Frederic says. “I’ve talked to all of them that are still living. They will not tell you.”

A number of people — including members of Metro — have pointed to this code of silence as a prime reason why Shakur’s murder hasn’t been solved.

“No witnesses would cooperate,” says Wayne Peter, a retired Metro detective who was the head of the homicide division when Tupac was shot, explaining the challenges the investigation faced in the A&E documentary series “Who Killed Tupac?”

According to Peter, Suge Knight showed up for police questioning three days after the shooting — with three lawyers in tow.

“The police would say to Suge Knight, ‘Who shot Tupac?’ and he would not answer, even though, certainly, he looked the guy right in the eye when the shooting was occurring,” Schumacher says. “There’s other people who certainly know who did it as well, and nobody said anything. This ultimately led to nobody being arrested for the crime.”

But if no one in the Death Row crew was talking, everyone else was, as theories about who was behind the shooting proliferated in the weeks and months that followed.

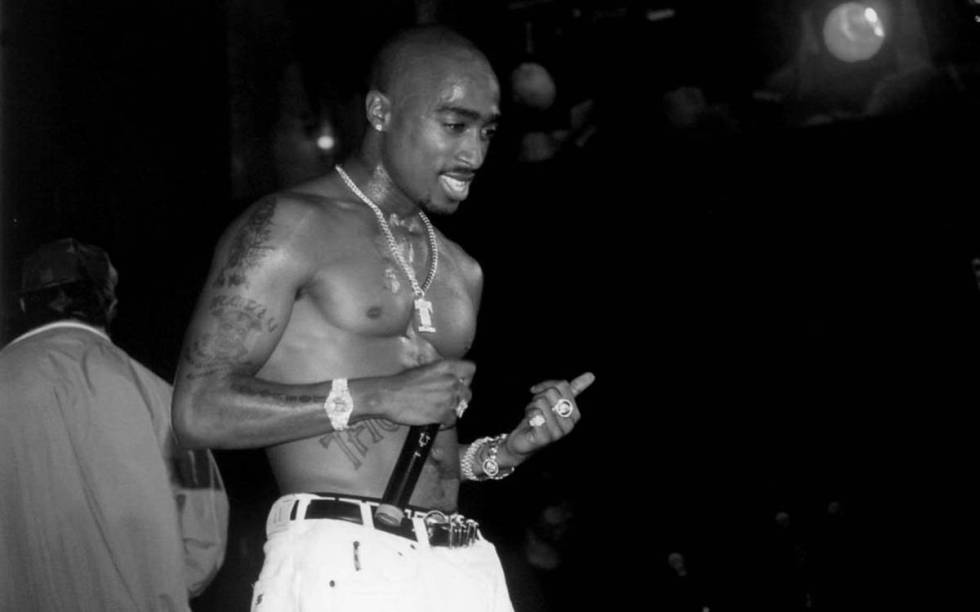

He discovered his voice — that bullhorn of a larynx — at an early age.

Literally.

“I just remember how impressed I was with the fact that his voice changed so early,” says rapper E.D.I. Mean, who grew up with Shakur in their native New York City. “His voice matured early on. The voice people got to know and love was intact pretty early.”

So was the intellectual curiosity that would form a central part of who he’d become as an artist.

“He was a forward-thinker and leader as a young youth,” Mean says. “He was always looking for ways to be creative. From playing in the streets to wondering what we were going to eat, he was always creative and had a plan.”

That creativity would propel Shakur to hip-hop immortality.

Though he died 25 years ago at the age of 25, Shakur’s legacy lives on prominently in the music he helped reinvigorate, re-imagine.

Shakur was many things: actor, poet, activist, agitator, thinker, fighter.

Above all else, though, he was a force of nature on the mic: It was as if he had jet engines for lungs, such was the power and command with which he delivered his words.

And what words they were.

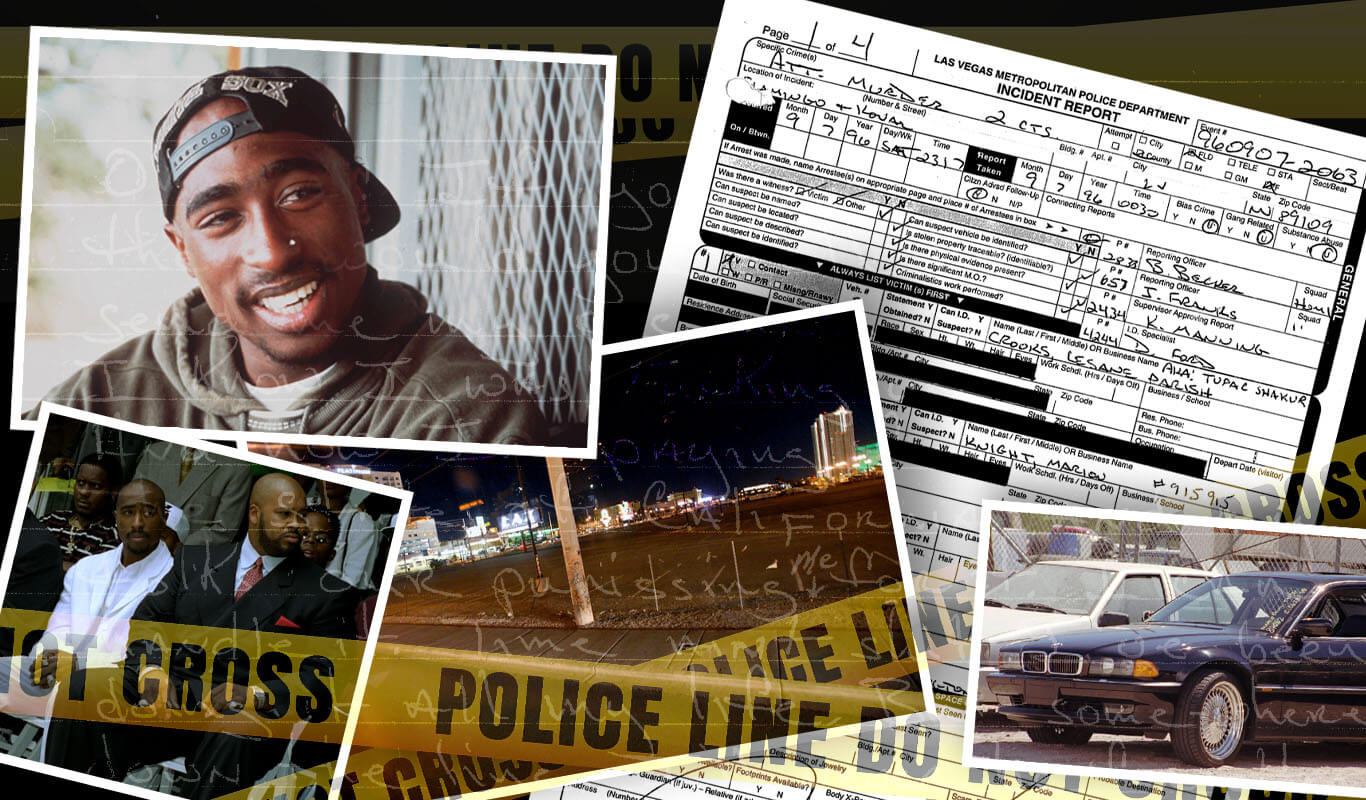

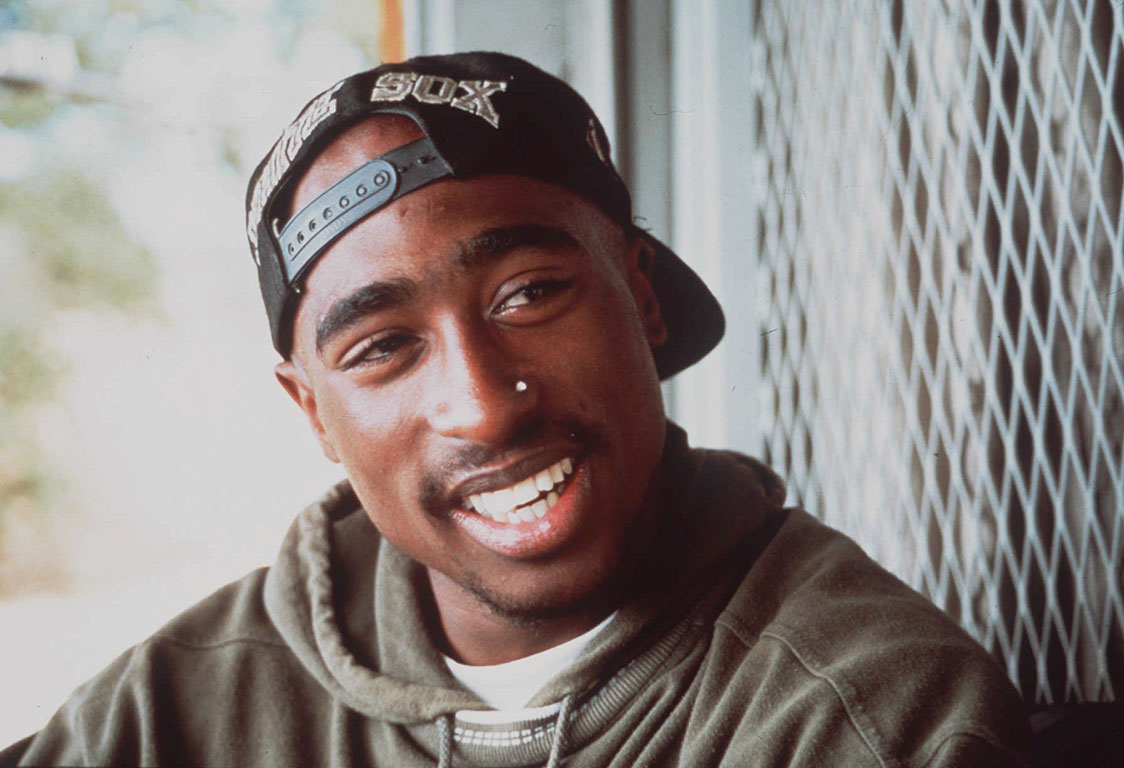

Tupac Shakur is shown in this 1993 handout photo. No arrests have been made in Shakur's death following the Sept. 7, 1996 shooting near the Las Vegas Strip. (AP Photo/File)

Tupac Shakur is shown in this 1993 handout photo. No arrests have been made in Shakur's death following the Sept. 7, 1996 shooting near the Las Vegas Strip. (AP Photo/File)One of Shakur’s greatest, most lasting contributions to hip-hop was tempering toughness with vulnerability. Yes, he had some of the most fierce, virulent rhymes ever, his lyrics so cutting at times, it was as if they were formed of razor wire.

But he evolved into an artist who also authored one of hip-hop’s most moving odes to mothers, “Dear Mama,” a tune capable of wringing tears from an eggplant, urged his peers to stop referring to women as “bitches” in their music and enjoined his female listeners to seek better lives for themselves via education and independence from men on songs like “Wonder Why They Call U” and “Brenda’s Got A Baby.”

At the time of his death, he was firebrand and feminist alike.

None of this is to overlook Shakur’s checkered past and bouts with the law: he went to prison for sexually assaulting a fan and was arrested numerous times for assault.

But he also seemed bent on bettering himself — and doing the same for his community, addressing numerous issues that society is still wrangling with.

“I think that’s why so many people still play his music, because his music is so relevant,” Stephanie Frederic contends. “He’s still speaking to the many issues that are going on today. He talked about racial injustice, he talked about police brutality, about poverty, about gender equality, about racial equality, all of those issues are still on the forefront today.”

And so too remains Tupac.

“You can walk into any barbershop on a Saturday, and you’re going to hear a Tupac song, you’re going to hear a conversation about ‘Pac or something he said or did,” Frederic says. “It’s amazing to me how he still lives in conversations, every day.”

There were arguments made that the killing was a result of the East Coast-West Coast hip-hop feud between Sean “Puffy” Combs’ Bad Boy Records label and Death Row Records, that Knight himself ordered the hit because he owed Shakur a large royalty payment and feared that the rapper was going to leave his label, even whispers that governmental entities wanted Shakur silenced for his ability to speak to and lead the African American community.

Nevertheless, the evidence continually points back to Anderson, his desire for revenge after getting assaulted by Tupac in public, and the rivalry between L.A.’s Bloods and Crips gangs (Anderson was a member of the Southside Compton Crips; Trayvon Lane and other figures in the Death Row crew were affiliated with the Mob Piru gang, a set of the Bloods).

The same type of gun used in the killing was found in a duffle bag with a Las Vegas mailing address inside it in the backyard of the home of the girlfriend of one of Anderson’s close friends. Perhaps most damning, Anderson’s own uncle, Southside Compton Crips member Duane Keith “Keefe D” Davis, implicates his nephew in a recording made by former Los Angeles Police Department detective Greg Kading as Davis was being investigated on drug charges in 2009.

Davis, who lives in Las Vegas and claims to have been in the white Cadillac with the gunman, later confessed to his role in the killing in 2018 after being diagnosed with cancer.

But what did Anderson have to say in his defense when all this was going down?

Frederic was determined to find out.

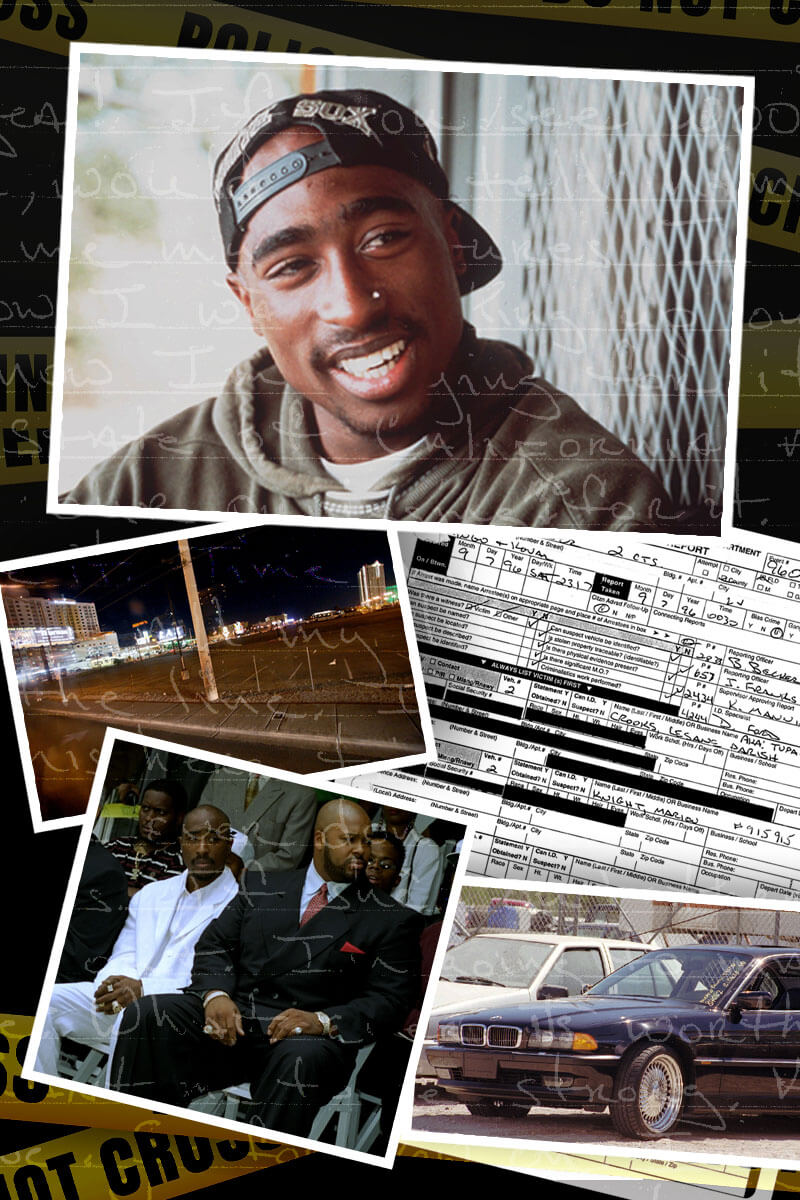

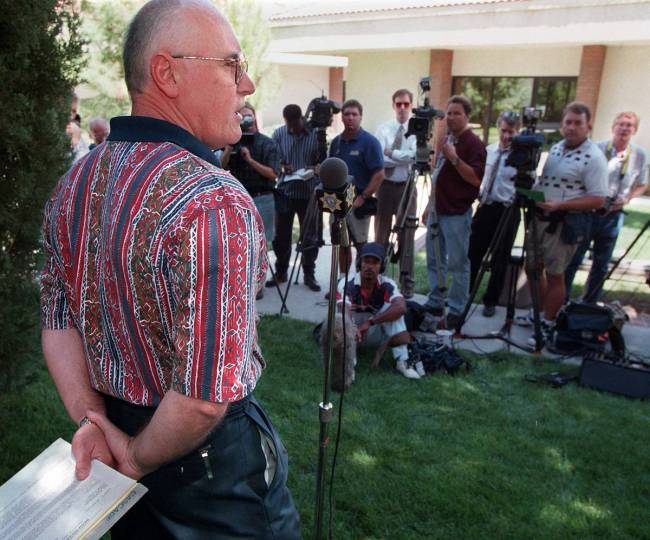

The intersection of Harmon and Las Vegas Blvd., in Las Vegas, Sunday, Sept. 8, 1996, where rap superstar Tupac Shakur and Death Row Records Chairman Marion "Suge" Knight were stopped and transported to the University Medical Center-Trauma unit after being shot Saturday night. (AP Photo/Jack Dempsey)

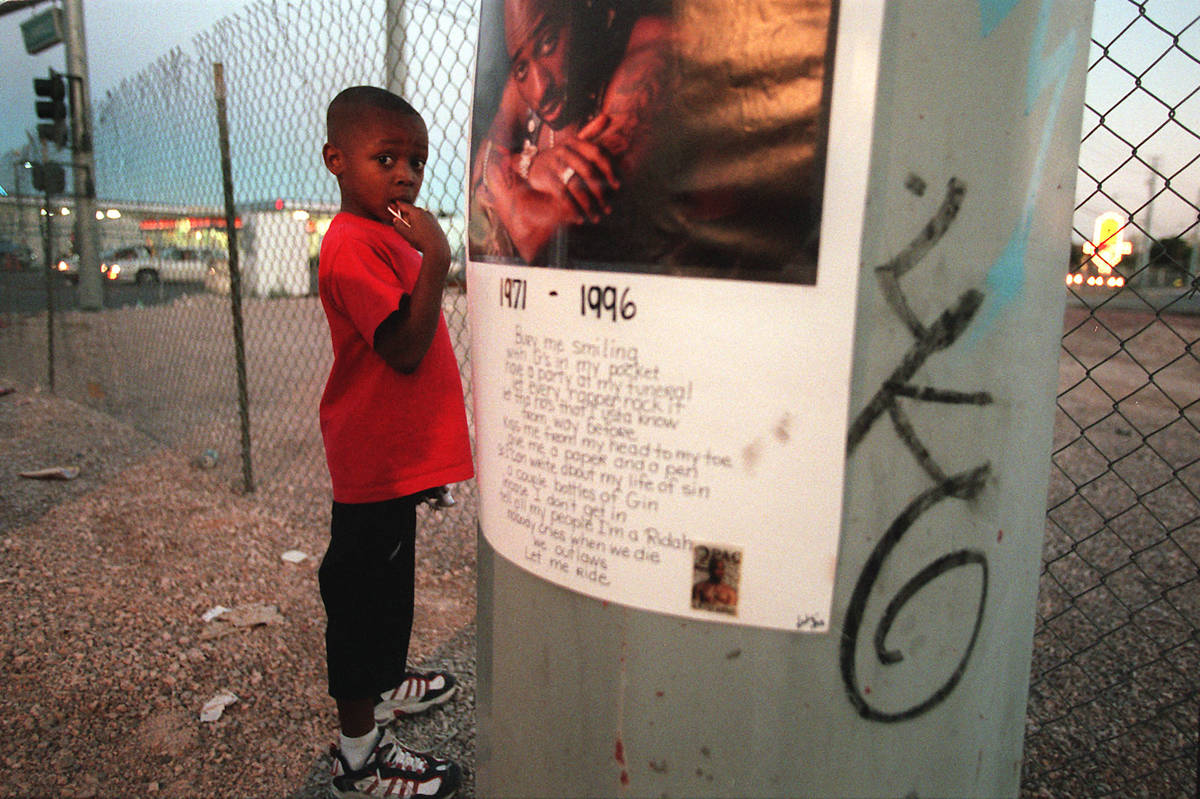

The intersection of Harmon and Las Vegas Blvd., in Las Vegas, Sunday, Sept. 8, 1996, where rap superstar Tupac Shakur and Death Row Records Chairman Marion "Suge" Knight were stopped and transported to the University Medical Center-Trauma unit after being shot Saturday night. (AP Photo/Jack Dempsey)  Fans dance during a candlelight vigil Sunday night on the second anniversary of the death of Tupac Shakur About one hundred people attended the gathering which was held at the location where Shakur was shot in Las Vegas. (Las Vegas Review-Journal file)

Fans dance during a candlelight vigil Sunday night on the second anniversary of the death of Tupac Shakur About one hundred people attended the gathering which was held at the location where Shakur was shot in Las Vegas. (Las Vegas Review-Journal file) Was the killer killed?

He smiles when there’s nothing to smile about.

He squirms in his seat like a kid sitting outside the principal’s office, awaiting an inevitable tongue-lashing.

Anderson looks anything but comfortable.

Flanked by his lawyer, he’s just been asked a point-blank question about a point-blank shooting: Did you kill Tupac?

He denies it, but his answer only raises more questions.

“When you analyze his answer, it doesn’t come back good for him,” explains Frederic, who conducted the exclusive interview just six weeks after Tupac’s death. “He stutters. His eyes shift.”

The interview is featured in “Who Killed Tupac?”

Landing it wasn’t easy.

“At the time, it was probably one of the most dangerous things to do, to try to secure an interview with the Southside Crips,” Frederic recalls. “I went down to Compton and started asking around, and they basically told me, ‘Get out of here.’ Not everyone had a cellphone back then, so I was handing out cards and, eventually, I got a callback.”

Anderson was getting death threats at the time. Word of his alleged involvement in the shooting had gotten out. He was feeling the heat; he wanted to tell his side of the story.

But his response probably did little to dissuade anyone who believed him to be the shooter.

So why was he never apprehended?

Even with the MGM Grand security footage, Metro police initially failed to make the connection between Anderson’s beatdown and Shakur’s shooting.

“We don’t think this guy even knew who Tupac was or who he was even dealing with,” Las Vegas police Sgt. Kevin Manning told the RJ in a story that ran the day before Shakur’s death.

Anderson was interviewed after the altercation, but no charges were filed at his request nor did police obtain his name.

In the initial aftermath of the incident, with Anderson speaking to the police as Shakur fled the scene, local authorities didn’t think that Anderson had the time to organize the hit.

“Because of the timing, we don’t believe there is any significance in regards to the shooting,” Manning elaborated in the aforementioned story. “He (Shakur) had already left. I suppose it is possible, but it’s also possible that pigs might be able to fly someday.”

Metro failed to talk with Anderson after the shooting, though Compton police later identified him and his gang affiliation, believing him to be the triggerman.

Less than two years later, on May 29, 1998, Anderson was killed in a gang-related shootout at age 23.

To some, this means that Tupac’s murder will never officially be solved.

To others, it means that it already has been.

“When the ’hood doesn’t believe that the police will solve it, they take matters in their own hands,” Frederic explains. “Has the case been solved? Not to public satisfaction,” she acknowledges, “but to the satisfaction of many others.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter and @jbracelin76 on Instagram