Mosque leader a ‘real life hero’ in Las Vegas’ Historic Westside

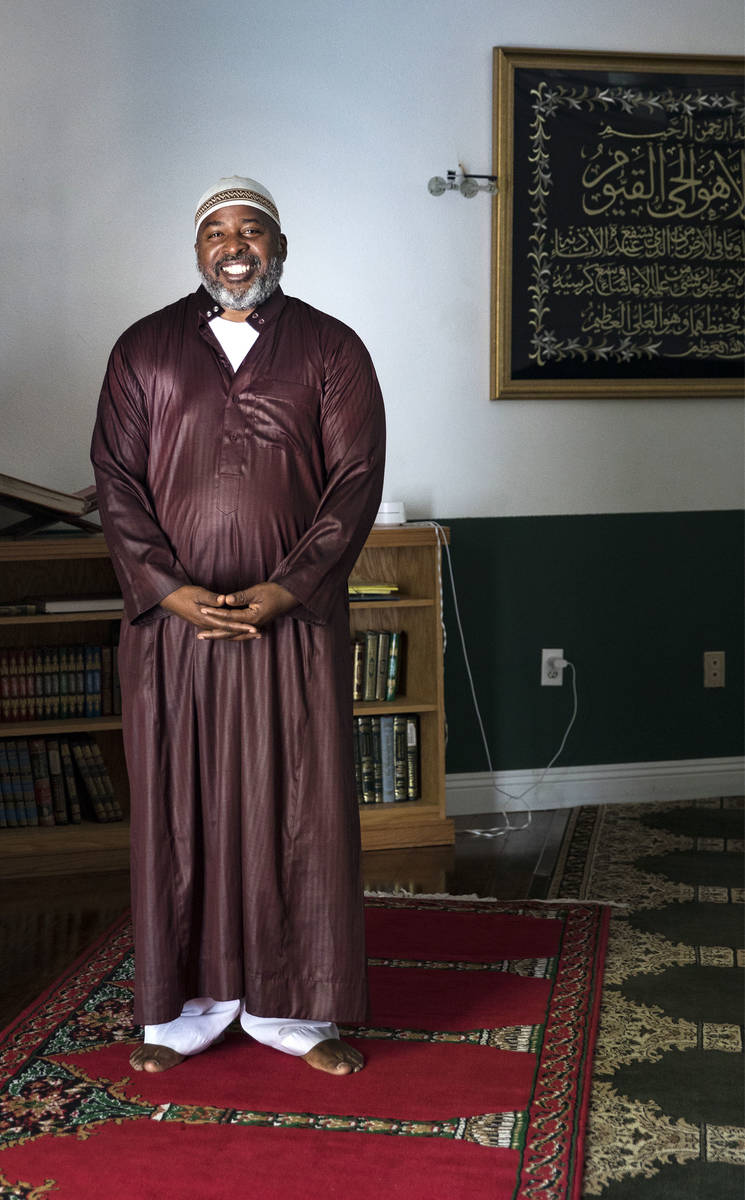

Before protesters spilled into the streets to declare Black lives matter, Imam Fateen Seifullah was quietly at work.

Outside the view of cameras, Seifullah and his congregation at Las Vegas’ oldest mosque, Masjid As-Sabur, set out to improve the lives of people living in the Historic Westside, taking action to a historically Black neighborhood that was being left behind.

“You name it, the neighborhood needs it,” Seifullah said.

Seifullah knows the everyday struggles of the Historic Westside, the struggles that go unseen outside the shadows of downtown. He sees the food insecurity. He knows the stress on parents who worry how they would pay for the technology that was given to their children for school if something happened to it.

He’s trying to make a difference.

Seifullah, 52, operates a food pantry, has driven out drug activity from the neighborhood, and runs a chess club for public housing residents, among other things.

From the streets to spirituality

Seifullah knows street activity because he lived it when he was younger. He was introduced to the culture as a child in Los Angeles, and was involved in dealing drugs later in Las Vegas.

“I wouldn’t say that I was a gang member, but I was engaged in every aspect of the life at one time, you might say,” he said. “So I know what it’s like to be a victim and a participant of street activity.”

Seifullah did two stints in prison for drug-related crimes, he said. Originally from a Christian background, Seifullah was introduced to Islam in prison.

“Growing up, he was really, you know, a knucklehead,” said Michael Elliott, a longtime friend who works at Seifullah’s store, Soulfully Scented.

But after his second time in prison, Seifullah made a commitment to change, walking the long spiritual path to where he is today. Now, he means so much to people in the Historic Westside as a community leader, Elliott said.

Seifullah sees his services now as a way to pay his debt to God and society for the harm he caused when he was younger.

Being an asset

Seifullah thinks it may have been destiny that brought him to religious leadership. His grandfather is a deacon, and his two older brothers are preachers. Islam, he said, called on him to be less of a liability.

Seifullah has made good on his word to be an asset. He and his wife helped Eric Chester reinvent himself, Chester said.

As a teenager in the 1990s, Chester said, he committed a murder that could have landed him life in prison. After 17 years behind bars, he said, he was released.

“When the world had thrown me away for the decision that I had made, they embraced me,” he said.

Chester, a Historic Westside resident, said Seifullah and his wife helped him start his own business. They’ve also had him work a homeless initiative and let him help with a tutoring program for kids.

Chester is still doing community service with the imam and running a business where he sells fashion accessories such as purses and wallets.

“It would be a tremendous loss to not have him here,” he said of Seifullah.

Taking control of a situation

In the 1990s, drugs and gang activity were out of control in the neighborhood, Seifullah said. So the mosque began an initiative to clean up the Historic Westside and close down drug houses.

After becoming the imam of Masjid As-Sabur in 1999, however, Seifullah realized the efforts were not enough and started providing more services.

Masjid As-Sabur helps people get food and provides assistance for utilities and rent. It offers tutoring for children in the neighborhood and performs outreach to let neighbors know services are available.

The mosque also helps both children and adults with reading, and offers computers to help people complete applications.

Seifullah has also been involved in an effort to bridge the divide between the community and the Metropolitan Police Department. After nearly a decade of collaboration in Metro’s community policing efforts, Seifullah said the mosque is close to a partnership with the police. Close, he emphasized.

Police had to change their mentality, but so did Seifullah’s congregants by looking beyond law enforcement uniforms.

“And it takes time,” he said. “It’s just not something that happens overnight.”

Stretch Sanders, a prominent racial justice activist, said he met Seifullah at a protest in 2016 and the two hit it off. Sanders later saw Seifullah and his mosque pay rent for people and shut down drug houses.

“I’m like, ‘Whoa, this man’s a real-life hero,’” Sanders said.

Sanders, who considers Seifullah a mentor, said Seifullah has also joined in protests against police brutality on Fremont Street.

“I mean, he has activism in his spirit,” Sanders said.

Road to long-term solutions

Seifullah said the Historic Westside needs more educational support, after-school support and tutoring programs, as well as more work-related training.

It needs redevelopment and someone who is interested in filling the lots that dot the neighborhood. It needs a sustained effort from the government.

He said some elected officials have claimed they don’t get enough community participation to move ideas forward. But the imam said it’s a lot to ask for community participation when people are trying to keep the lights on and put food on the table.

Seifullah, however, isn’t done helping. As long as there are vacant lots and economic woes in the neighborhood, there is still work to do.

He said he has just tried to be an example.

“And people have followed,” he said.

Contact Blake Apgar at bapgar@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5298. Follow @blakeapgar on Twitter.