Millennium madness: Y2K and the party that changed Las Vegas

Twenty-five years ago, many Las Vegans were bracing for the end of the world.

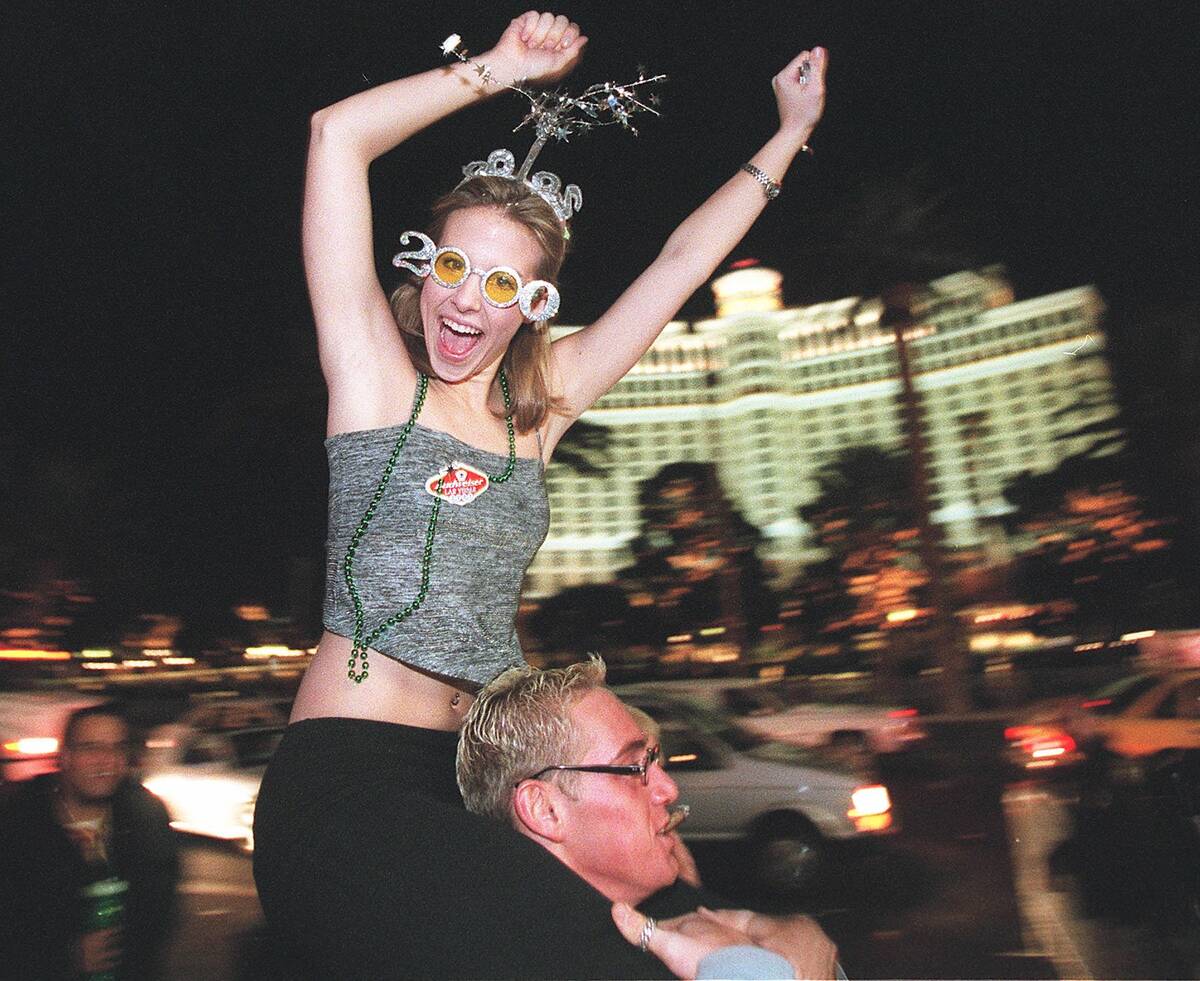

Others were anticipating the largest party the city had ever seen.

More than a few were ready for both.

It seems silly in retrospect, but in the 1990s, computers were so limited and memory was so expensive that years often were shortened to their last two digits. Heading into the new millennium, there was a very real chance that computers across the world would fail after reading the year “00” not as 2000 but as 1900.

Common fears of the “millennium bug” or “Y2K glitch” included airplanes falling from the sky, prison cells springing open, widespread power outages and bank balances disappearing overnight.

As businesses and government agencies worked to prevent that from happening, casino leaders saw dollar signs. With equal parts greed and hubris, many took typical prices and moved the decimal point one place to the right. Hotel nights and concert tickets hit unheard-of asking prices of $2,500.

Since Dec. 31, 1999, fell on a Friday, hospitality giants tossed all worries aside and assumed there was no place people would rather be than Las Vegas to ring in the new millennium — even though, technically, the millennium didn’t start until 2001, the same way we transitioned from 1 B.C. to 1 A.D. with no Year Zero in between.

Y2K preparations

The Nevada Department of Prisons got the ball rolling. Knowing it would have sentences that extended into the new millennium, the agency upgraded to a four-digit computer system in 1987.

State and local governments started tackling the problem in late 1995.

In November 1999, the federal government put a $100 billion price tag on Y2K compliance.

Beyond that, District Court officials limited activity for the first two weekdays of 2000, including pushing back proceedings in one of the trials connected to the sensational killing of a du Pont heir’s girlfriend.

Las Vegas reservoirs were filled to capacity with 1 billion gallons of water ahead of Dec. 31 allowing for four to five days of drinking water.

In early December, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints grounded its missionaries and workers, telling them not to travel by air between midnight Dec. 30 and midnight Jan. 5.

The gentleman’s club Cheetahs decided to close its doors early on New Year’s Eve, potentially one of its biggest nights of the year, because of what its marketing director said were fears that “there’s going to be too much chaos.”

Unprecedented prices

If any group could have been accused of terrible planning, it was the casino owners as millennium madness swept over the hospitality industry like a virus.

In mid-February, Caesars Palace was offering rooms over New Year’s Eve at $2,000 a night with a four-night minimum stay or $2,500 a night for three nights. Bellagio set rooms at $2,000 per night with a three-night minimum.

It wasn’t just the leaders of the luxury resorts who bought into the silliness. Circus Circus was asking $450 a night for four nights, while Texas Station shocked the public conscience with rates of $750 a night with a three-night minimum.

Barbra Streisand’s Dec. 31 show at the MGM Grand was announced in April with tickets ranging from $500 to $2,500 a pop. A second show on Jan. 1 was added at the same price point. After that, all bets were off.

Mandalay Bay offered up Bette Midler on Dec. 31 and Jan. 1 with tickets ranging from $95 to $500. The Rio was asking $400 to $1,000 to see Rod Stewart.

The Fremont Street Experience charged $100 a head to see The Guess Who, Creedence Clearwater Revisited, Starship and REO Speedwagon. That was quite a leap from the previous year, when revelers could see Rio headliner Danny Gans, Starship and Bachman Turner Overdrive for $10.

A million visitors?

Casino executives certainly had reasons to be optimistic.

In early July, the Review-Journal reported that anywhere from 750,000 to 1 million people were expected to greet 2000 in Las Vegas. One financial analyst gushed that New Year’s Eve would be the largest event in the city’s history.

By October, the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority had revised the number of expected visitors to 275,000.

“I don’t know where that number came from,” LVCVA spokesman Rob Powers said of the 750,000 claim.

Even that lower number would have been a success considering anyone younger than 18 would be banned from the Strip after 6 p.m. Dec. 31 and there would be nothing to entertain those who gathered there. Not so much as a single firework.

“We presented some options for entertainment, but the consensus was there’s so much entertainment being provided by the hotels, there was no need to do anything outside of that,” said Rossi Ralenkotter, the LVCVA’s then-vice president of marketing.

A concert or other entertainment “would increase the number of young people,” Powers said in December. “That would serve as a magnet for young people in Phoenix and Southern California.”

In 1999, this apparently was a bad thing.

Struggles to sell

Ultimately, the sticker shock proved to be very real. High prices combined with Y2K fears kept many potential visitors in their homes.

The most expensive tickets to see Streisand sold out first, and only a few single tickets in the $500 and $750 tiers remained in mid-December. All of the $95 Midler tickets were gone the day they went on sale in July. But most other shows struggled.

The $150 tickets to see Don Rickles and Cybill Shepherd at the Desert Inn weren’t exactly being gobbled up. As much as 80 percent of the tickets for Wayne Newton at the Stardust, listed at $275, were expected to be comped.

“A lot of the hotels got so worried about not having a big name for New Year’s, some of them really overpaid their acts, sometimes four and five times what they are worth,” Steve Schirripa, the Riviera’s entertainment director, told us at the time. (Yes, that Steve Schirripa, who was weeks away from debuting as Bobby Bacala on “The Sopranos.”)

By October, the LVCVA had unveiled a $2.5 million advertising campaign aimed at filling the valley’s hotel rooms.

On Dec. 7, the RJ reported room rates were down as much as 60 percent from the initial ask. One anonymous hospitality executive estimated as many as half of the city’s 120,000 hotel rooms were still available.

Caesars Palace ended up giving away 80 percent of its rooms to gamblers, while Bellagio comped 70 percent of its inventory.

By Dec. 27, you could have gotten those three nights at Texas Station, once set at $750 a night, for $399 — total.

Change for the better

The calendar finally rolled over to 2000 with a whimper, not a bang.

Clark County spokesman Doug Bradford said in the following days there were “no significant problems” with computer systems. “There were a few glitches here and there, but we were able to fix them the next morning.”

Tod Surmon, a 26-year-old assistant wrestling coach at Stanford University, died after climbing a light pole near Paris Las Vegas. Clark County Coroner Ron Flud said at the time that Surmon died from a combination of electrocution and trauma from falling 30 feet to the ground.

Aside from that, county officials described it as one of the calmest New Year’s Eve celebrations in years.

The only reported power failure had nothing to do with computers. A foil balloon landed on a substation wire early on Jan. 1 and briefly cut off electricity to The Mirage and nearby hotels.

As recently as two weeks before, an LVCVA spokeswoman said she was still expecting 99.6 percent hotel occupancy on Dec. 31, which would have matched the previous year. The actual tally was 85 percent.

Final estimates pegged the number of visitors at 240,000. Police estimated 300,000 revelers — visitors and locals — gathered on the Strip, which was about 50,000 fewer than the previous year. Only 10,000 or so people showed up at the Fremont Street Experience, a fifth of the crowd in 1998.

“When we all analyzed what was going on, we misread the demand because we underestimated the activities outside of Las Vegas,” Mirage Resorts Inc. spokesman Alan Feldman told the RJ heading into that holiday weekend. It never dawned on hotel leaders, he said, that other cities would be “treating this as a marketing opportunity.”

By taking all the festivities indoors, the “entertainment capital of the world” offered little for the rest of the world to see. As all the major networks broadcast live from Las Vegas, the city wilted in the spotlight.

Mayor Oscar Goodman, one of the greatest cheerleaders this city has ever known, struggled to remain upbeat.

“In other cities, one celebration was more spectacular than the next,” Goodman said in the new year. “We certainly didn’t have the punch here that I saw elsewhere, but everyone had a good time, and that’s the main thing.”

The debacle proved to be a turning point for Las Vegas.

The city hosted a $500,000 fireworks display on Dec. 31, 2000.

The following year, “America’s Party,” the coordinated campaign that’s made Las Vegas the place to be on New Year’s Eve, was born.

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567.

Y2K prep gets silly It wasn't uncommon for people to stock up on canned goods. Some bought a generator just in case. If your VCR were to stop recording your favorite shows, the Review-Journal told readers to set the machine's clock back to 1972, because that year's dates corresponded with those in 2000. The RJ's classifieds, meanwhile, portended a horror show. Y2K provisions were being sold with the advice to "order now" and "avoid last-minute delays." That was on June 20, 1998. Hucksters promised to tell you "How to survive Y2K" for only $9.95 plus $3 shipping and handling, and they sold preparation checklists for $19.99. Dodge M-37s were marketed as "Y2K survival mobiles." An Uzi Model A 9mm Carbine was offered with the question, "Y2K is coming. Have you got yours yet?" An "AR-15 Y2K special" included the gun, scope and case along with extra magazines and 2,400 rounds of ammunition. Elsewhere, a display ad promised "1,690 pounds of grains, legumes, honey and milk in 37 heavy-duty food buckets," while a jewelry store touted its "Y2K millennium silver coins" with the warning, "Be prepared with barter money just in case!" During the Soldier of Fortune convention at Cashman Center that September, author/survivalist Ragnar Benson told attendees that 15 breeder pigeons could provide two squabs a week for food while three doe rabbits and a buck could eventually yield two hares a week for consumption. Another alternative, Benson said, were dogs and rats, which he referred to as "urban meat."