Las Vegas veteran ready for Normandy return but needs help

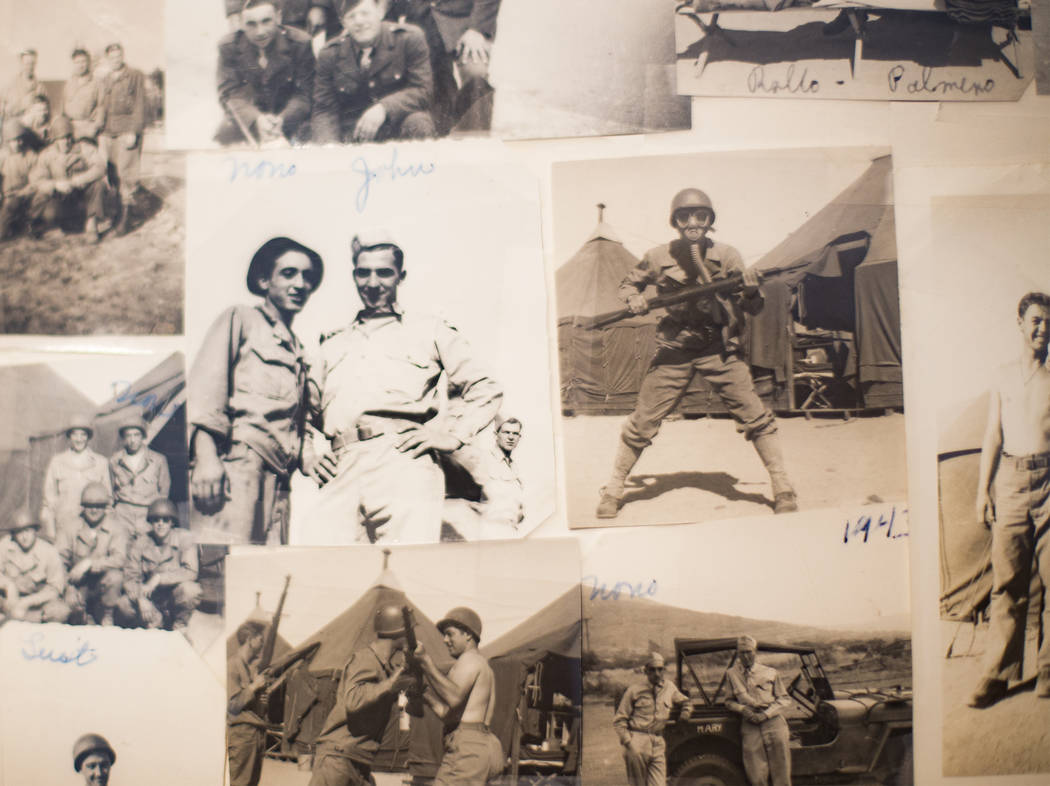

At 96, Onofrio “No-No” Zicari is finally ready to return to the spot where he spent the worst hours of his life.

Zicari was a fresh-faced 21-year-old Army private from Geneva, New York, when he and his comrades were called upon to storm France’s Normandy coast on D-Day — June 6, 1944 — during World War II.

The Las Vegas resident, who helped to operate the duck boats that ferried supplies between ships and land, survived the perilous landing with only minor wounds despite the sinking of the landing craft after it was hit by German gunners.

Still, the petrifying hours when he and other members of his unit were pinned on the beach by gunfire and artillery shook him to his core. He wasn’t sure he wanted to ever see that spot again.

But with the 75th anniversary of D-Day just a couple months away, he wants to return to the beach known as “Red Easy” to visit his Army buddies who were put to rest there.

Therein lies a problem.

While Zicari was promised a free trip, which includes seven nights in Normandy, covered by the nonprofit Forever Young Senior Veterans, he needs to take his caretaker with him.

“I’m 96; I can’t go alone,” he said this week at his home. “I want to go back there this June and see what’s left. … They say the pillboxes are still there, so I’m anxious to see that.”

Fundraising effort lags

Diane Hight, the founder of Forever Young Senior Veterans, said she arranged Zicari’s trip after receiving a call last year from former Nevada Sen. Dean Heller’s office, which promised to help raise the funds.

But because Heller is no longer in office, the organization is a little over $6,000 short of what it needs to send Zicari and his caretaker to Normandy. As of Friday, the fundraising effort to close the gap had raised just $50 in a single donation.

Hight, 61, created the Tennessee-based nonprofit in 2006 as a way to honor veterans from World War II, Korea and Vietnam and grant them an opportunity to return to the places they fought.

“When you take a group of veterans back that fought together, they can all talk about it with one another, and it’s very healing,” Hight said. “So many suffer silently. When they get back, they have a confidence they didn’t have before. I do this out of love and passion for the greatest men and women who ever lived.”

Zicari said he would have gone back sooner, but he could never afford it.

He isn’t sure if he will ever get closure from the memories forever seared into his memory, such as the soldier with fiery red hair who sat on his helmet laughing while holding his guts in with his hands, even as a German pillbox continued to fire machine guns in their direction.

“I’m lucky. I’m going home,” the man yelled at him.

Nightmares, a few fond memories

Or the medic who treated Zicari’s wounds about an hour before being killed himself. Zicari believes his name was Fisk.

Even after all these years, Zicari still has nightmares about Normandy and the two other battles he survived, including the Battle of the Bulge. Fireworks and the smell of diesel fuel also bring him back to the war, he said.

He said soldiers in the war remember going without showering and eating and cooking out of helmets. As an Italian-American, though, he has a memory that few other vets share: making spaghetti out of burdock, an edible root, for his company.

Zicari was at the port in the Marseille, getting ready to deploy to Japan, when the end of the war was announced. He was elated.

He said his Catholic faith and the company’s priest helped him get through the war. Now he hopes some generous strangers will help him get back.

Maybe, he said, he can find the place on the beach where he was pinned down 75 years ago.

“There, I was in a state of grace,” Zicari said. “I didn’t want to die, but I wasn’t afraid.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.