Lake Mead likely to reveal more skeletal secrets as waters recede

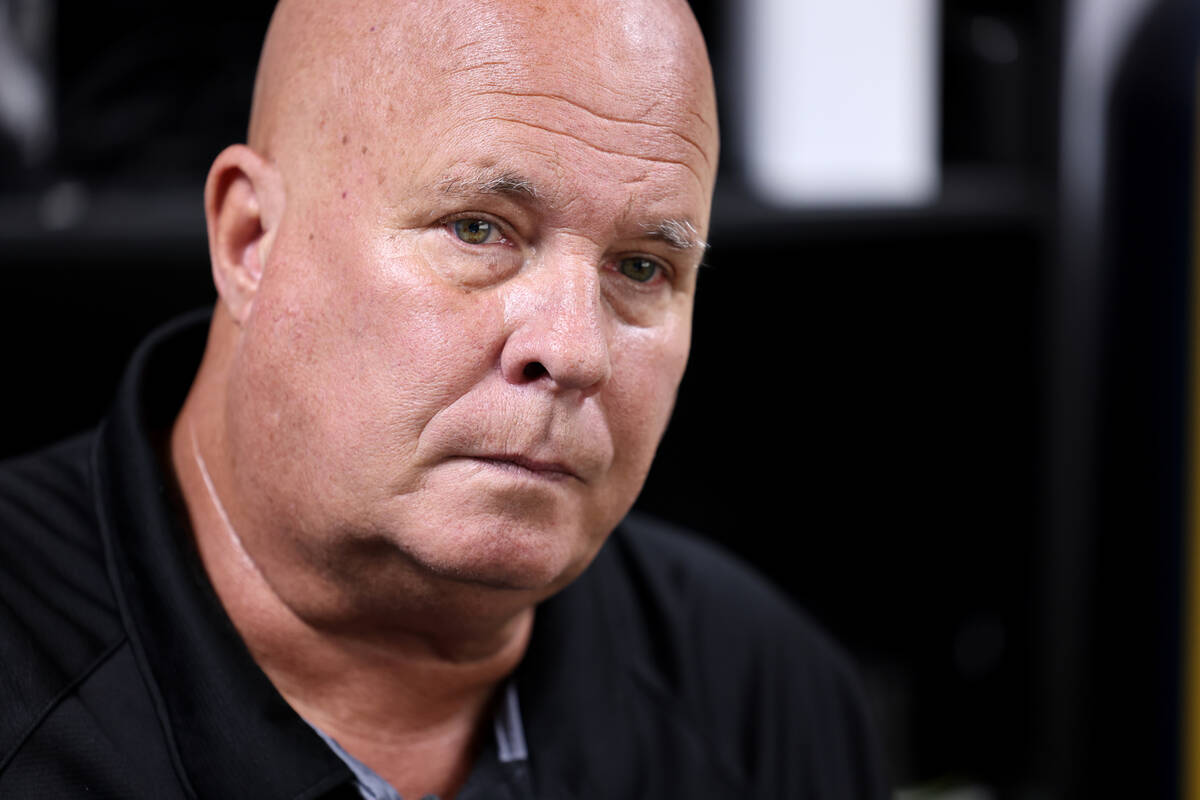

Steve Schafer knows better than most how dangerous a place Lake Mead can be.

The Henderson resident and two co-workers at the Las Vegas Valley environmental remediation business Earth Resource Group have volunteered their time to find and recover at least 10 bodies in the waters of Lake Mead National Recreation Area since 2013. The trio uses an advanced underwater remote-operated vehicle, an underwater GPS system and deep-water sonar technology at the request of the National Park Service to find those who go missing in the lake.

“We do it to give back to the families,” Schafer said, adding he expects more remains will be found in the lake’s waters and along the shoreline in the coming years.

“There are a lot of bodies which have still not been found at the bottom of Lake Mead,” Schafer said. “Most are just legitimately drowning victims, but I’m sure there are some nefarious ones out there, like the news is reporting and the (body in the) barrel. I’m sure there are going to be more.”

On May 1, the body of a male shooting victim was found encased in a barrel at Hemenway Harbor. The curious circumstances have prompted extensive, worldwide media coverage and speculation that the unidentified man was the victim of a mob hit.

Since that discovery, Lake Mead’s rapidly declining water levels have revealed more of the lake’s secrets, with four more sets of skeletal remains discovered at places including Swim Beach and Callville Bay. The latest set of remains were found at Swim Beach on Monday.

So what else could the lake be hiding? Only time will tell, but Clark County Coroner Melanie Rouse said Thursday that the discoveries are a reminder of the dangers to be found at the recreational area.

“We always want the public to be aware of safety measures and make sure they’re being diligent about their environment, whether in heat or an open body of water,” Rouse said.

Deadly waters and climate change

Jeff Burbank is a former reporter for the Las Vegas Review-Journal. In 1994, he researched for the newspaper how many people have gone missing at the recreation area. He found that since the National Park Service began keeping records in 1937 until 1994, some 59 people were listed as missing or presumed drowned at the recreation area.

“I was kind of shocked that those people could still be down there in those depths for so many years,” Burbank said.

Many of the missing were boaters whose vessels were sunken by wind or waves. Some went under while fishing or swimming. One of the missing was a parachutist. One took their own life. One died in a plane crash. One was swept away by a flash flood. All had one thing in common: Their bodies were never recovered despite being in the lake, in most cases, for decades.

Since Burbank conducted his research, Lake Mead has claimed many more victims. In 2017, Outside magazine called the recreation area America’s deadliest national park. The magazine found that from 2006 through 2016, 275 people lost their lives at the 1.5 million-acre park east of Las Vegas. That’s about 100 more than at the second-deadliest national park, Yosemite National Park, and 120 more than third-deadliest Grand Canyon National Park, according to Outside.

And now, with waters receding during two decades of drought, some of those long-missing bodies are finally showing up. The latest projection from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation indicates Lake Mead could drop another 20 feet by the end of 2023. The lake has fallen about 170 feet since the drought began in 2000 and sits at 27 percent capacity, according to the Bureau of Reclamation.

The park service did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

Giving families closure

In many cases, those who go missing at Lake Mead are found right away by authorities. But in the others, Schafer and his co-workers often are asked to get involved.

The first recovery Schafer’s crew carried out was in April 2013. Creech Air Force Staff Sgt. Antonio Tucker, 28, went missing while swimming in choppy waters on Lake Mead almost a year earlier. Schafer, after reading media accounts of Tucker’s disappearance, decided he wanted to help.

What followed was a frustrating maze of bureaucracy in which Schafer learned he first had to get permission from Tucker’s family to assist in the search. Then, he had to get a permit from the park service.

After all those steps were taken, Schafer and his crew used a Video Ray Pro 4 remote-operated vehicle, Blue View Sonar and an underwater GPS system called the Smart Tether from their boat. The sonar images from the ROV, traveling along the murky bottom of the lake, provided images allowing Schafer and his crew to locate Tucker’s body. The crew then worked together to bring the body to the surface using a makeshift snare attached to the ROV.

Tucker’s body was raised from a depth of about 280 feet. Tucker’s family was extremely grateful.

“We took them out there, they put a wreath down, and it gave them a little bit of closure,” Schafer said.

The most recent successful recovery Schafer’s team carried out was the body of a jet skier who died on the lake in July near Boulder Islands on Lake Mead, but the park service failed to recognize the team’s service publicly when the body was found.

A common thread runs through every recovery, Schafer said. None of the victims was wearing a personal flotation device, he said, and all underestimated the inherent dangers of the body of water.

“Everybody thinks they are Michael Phelps in the water, but you panic,” he said. “A good swimmer doesn’t seem to matter a lot at all.”

Schafer said the searches are an incredibly rewarding way to give back to the community.

“It’s hugely important,” Schafer said. “The family really wants that body recovered, and it gives them the closure they’ve never had.”

Contact Glenn Puit at gpuit@reviewjournal.com. Follow @GlennatRJ on Twitter. Review-Journal staff writer Briana Erickson contributed to this story.