Developers named Arizona Charlie’s for distant relative

Many assume that Arizona Charlie, of local casino fame, was a character created for corporate marketing purposes like Ronald McDonald or Bob’s Big Boy.

The truth is, there was indeed an Arizona Charlie, and he was an epic Western figure, although many of his exploits need to be taken with a grain of salt — or maybe the whole shaker.

The 1989 book penned by Jean Beach King, a direct descendant, is titled “Arizona Charlie: A Legendary Cowboy, Klondike Stampeder and Wild West Showman.”

The casino namesake’s life is explored in great detail using newspaper accounts, stories from surviving relatives and Arizona Charlie’s own diaries and scrapbooks.

Abraham Henson Meadows was born, by his own account, near what is now Visalia, Calif., in a Conestoga wagon under a giant valley oak that shielded it from a late falling snow on March 10, 1860.

His parents were Southern sympathizers, and before the boy turned 3, his father, angered by the actions of President Abraham Lincoln, redubbed him Charlie.

In 1877, the family moved to Tonto Basin, Ariz., around 90 miles east of Phoenix, where they settled a new ranch. Initially, the family was friendly with the local Apaches, but in 1882 trouble began brewing.

The 21-year-old Meadows left the ranch in pursuit of a band of Apaches who had been cutting a swath of destruction among his neighbors. He was reluctant to leave the ranch unprotected, but his father assured him that he and two other sons had the situation in hand.

“I was more than happy to help in this campaign against the deadly marauders, who had committed so many atrocities against my friends and neighbors,” wrote Meadows in his later years to Arizona State historian Effie Keen. “At that time, ‘the only good Apache, was a dead Apache.’ ”

If Meadows had wanted to fight the Apaches, he should have stayed home. An early morning raid on July 15, 1882, left his father dead and two brothers wounded. His brother Henry later died from his wounds.

Meadows returned to tend to his family and missed the Battle of Big Dry Wash, the last major battle between the U.S. Army and the Apaches in Arizona.

The event was a formative one for Meadows, and he claimed that it drove him to become a crack shot with his Winchester rifle and an expert rider and roper.

He displayed these skills by winning a roping contest in a rodeo at Payson, Ariz., in August 1884. That rodeo is one of several claimants for the contested title of first rodeo.

Meadows continued ranching and rodeo contests and competed with notables such as the famous scout Tom Horn.

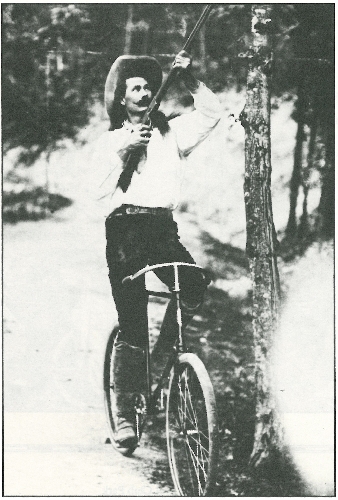

In 1890, Meadows was offered a job in the new field of cowboy performance. He traveled to Australia to perform in a Wild West show attached to a circus. This was followed by a European tour with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

It was Buffalo Bill Cody who gave Meadows the name “Arizona Charlie,” expanding on a nickname, “Arizona,” he had already gained. Soon after, Meadows had his own troupe and shows.

When gold was discovered in the Klondike, Meadows organized a party to make the trek to the Yukon. He and a crew rounded up 200 burros, loaded them with supplies and headed north. His plan wasn’t to mine but to mine the miners, selling burros, supplies and labor. All was going well until a section of a glacier broke free and an avalanche swept away most of his fortune.

After an arduous journey, Meadows and his party arrived in Dawson, in the Yukon Territory. He was involved in several moneymaking enterprises, including the establishment of a newspaper and building and operating the Grand Opera House, a lush, modern building constructed in a place where supplies were hard to come by.

When the gold panned out, Meadows sold the opera house for a third of what it cost him to build and headed south making a few extended stops along the coast on his way back to Arizona.

He remained a man of great schemes. He made plans to capture the island of Tiburon in the Gulf of California. He planned to import dirt-cheap cattle from Mazatlan, Mexico. He founded another newspaper, the Valley Hornet in Yuma, Ariz. And he worked to establish a hot air navigation company that never got off the ground.

Over the years, Meadows rubbed elbows with the great and the infamous. Zane Grey based a novel on one of Meadows’ exploits.

He numbered Will Rogers, Cody and Horn among his friends. He met potentates, princes and renowned scoundrels. He lived long enough to see the exploits of his fellow cowboys become a staple of a new form of entertainment, the motion picture.

At least that’s how he told it, but Arizona Charlie was never a man to let the facts get in the way of a good story.

“Charlie never stood in the way of a good story,” wrote his distant relative King, “especially those about himself, and it did not matter whether the yarn was true or not. He had an uncanny knack for mixing fact with fiction, and it amused him to play upon the tenderfoot’s innocence.”

Meadows’ cousin, historian Don Meadows, put it a little more bluntly.

“Don Meadows didn’t speak highly of (Arizona Charlie),” said Mark Hall-Patton, director of Clark County Museums. “He said he wasn’t quite what he said he was, and the book is not altogether accurate. He may have gone as far as to refer to him as a con man.”

Hall-Patton knew the historian from several historical associations in his earlier days in California. He said Don Meadows has since died, but he was the most knowledgeable person on Southern California, Baja California and Southwest history. He is one of the many sources King used for her book.

Ernest Becker, another distant relative of Charlie Meadows, came to Las Vegas in the late 1940s and made his mark in real estate. As a developer, he would develop lots, sell them to builders and then build and operate shopping centers to support the new homes. One of these included a Becker family-owned bowling alley.

Becker’s youngest son Bruce was eventually put in charge of the bowling alley. After a decade and a half of operating it, Bruce Becker had a radical idea.

“Since the casinos are adding bowling alleys to their casinos, I want to add a casino to my bowling alley,” he joked to reporters when the casino project at 740 S. Decatur Blvd. was announced in 1987.

The family decided that “Ernie’s” or “Becker’s” lacked the necessary flair for a casino name. So they reached up the family tree to Arizona Charlie, and the name worked well.

Arizona Charlie Meadows spent his last days in Yuma. On Dec. 9, 1932, the 72-year-old died when he made the fatal mistake of operating on his own troublesome varicose veins with a pocketknife.

Contact Sunrise/Whitney View reporter F. Andrew Taylor at ataylor@viewnews.com or 380-4532.