Dog-loving millionaire left fortune to Scottish charity

Fifty-four days ago, a lonely old man put a gun to his head and set off a mystery. He fell to the floor in his closet, where his only two friends would find him later.

No obituary ran for William Roberts Lindsay. There were no services. His body was cremated and arrangements he had planned well in advance were begun.

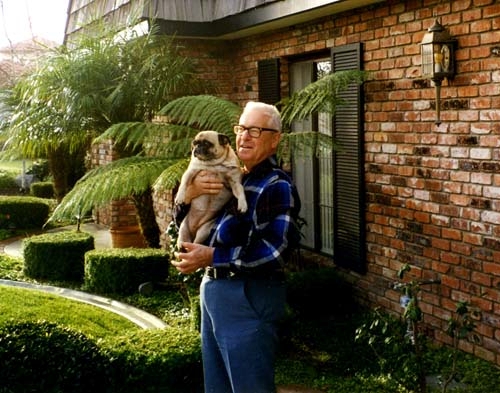

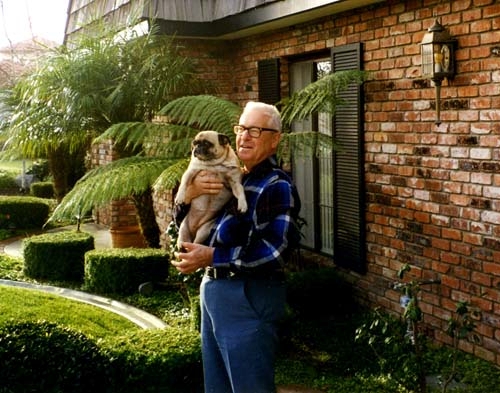

His barber, Elton Marvin, who owns a shop on East Sahara Avenue, would get his beloved dog, a pug named Midget.

His other friend, a former neighbor, UNLV chemistry professor Vernon Hodge, would get the modest contents of his house and a few dusty old coins in a safe deposit box.

His two cousins back East would get $250,000 each.

The National Trust for Scotland, a historic preservation organization, would get the rest. Probably millions.

Yes, millions. Bill Lindsay left the bulk of his apparently vast fortune to an organization he had no connection to, in a country he had never visited.

“He had everything you and I could want,” Hodge said. Money, a house, his good health. “And yet he was still unhappy for some reason. I think it was loneliness.”

Lindsay was 79, an avid hockey fan, a heavy reader of mysteries. He was born in Ohio, and his cousin said he received a law degree from Ohio State University. He was a lifelong fan of the university’s sports teams.

But he made his fortune in California. He practiced law there, although no one could say exactly what kind. He also became a businessman. He and two partners pooled their money to buy failing companies. They would fix the companies and sell them for a profit.

“It was kind of like flipping houses,” Hodge said.

Lindsay made a million dollars on the first company they sold, Hodge said.

Over the years, Lindsay’s income from his work and his investments began to accumulate.

But he never married. Never had children. By all accounts, he never made many close friends. He lived with his dog, one in a series of pugs he’d named Midget.

In 1982, he left his house overlooking the beach near Carmel-by-the-Sea, a wealthy town along the central California coast. He bought a modest three-bedroom house in southeast Las Vegas. He said then that he was tired of paying the high taxes in California.

He kept the California house for a while, but his cousin, Lois Thompson, said he eventually gave it away to a cancer foundation, as best she could recall. Homes in that area now sell for millions.

Lindsay was a private person, even then. He barely knew his neighbors, and he would still spend several months each year in California.

A few years after Lindsay moved into the Las Vegas neighborhood, Hodge bought the house across the street. The two men would wave to one another, but that’s about as far as their relationship went.

But Hodge, 70, said Lindsay’s gardener apparently quit one day while Lindsay was out of town. Hodge took it upon himself to keep the man’s lawn watered and cared for.

When Lindsay returned, the men struck up a conversation. They became closer. They became friends.

A few years later, Lindsay moved to a larger house in a guard-gated community in Henderson. His friendship with Hodge and Marvin, his barber, continued.

Lindsay and Thompson, 83, his cousin, would talk on the phone every Thursday, she said.

She would visit him here now and then, but Lindsay never visited her at her home in Hilton Head Island, S.C. She said he was afraid of flying.

Lindsay’s father and sister both died many years ago. His mother, though, lived into old age. Thompson said she had a debilitating stroke, and the experience changed Lindsay forever.

His mother survived, but she needed round-the-clock care. She lived in Cleveland, and Lindsay spent a long time there caring for her. He eventually put her into a nursing home, but he could not stand it, Thompson said. He instead hired full-time caretakers.

From then on, Thompson said, her cousin was worried about what could happen to him in old age.

“He said he didn’t want to end up like his mother,” she said.

Hodge said Lindsay’s only real health problem was high blood pressure, for which he took medication.

But Hodge said Lindsay was afraid of Alzheimer’s, more so than he should have been. He said his friend was so sharp of mind he still did his own income taxes.

In the last decade or so, Lindsay began to give away his money.

Hodge, who is overseeing the trust that contains Lindsay’s assets, said his fortune was considerable. Despite retiring almost 30 years ago, he still had a multimillion-dollar income each year from investments.

No one is sure when he became interested in Scotland. Thompson said he had learned some years ago that his ancestry traced back to that country. But he had no relatives there that he knew.

In 1999, he donated $2 million to Glasgow University, which used the money to establish the William R. Lindsay Chair in Health Policy and Economic Evaluation. The newspapers over there covered it, but none interviewed Lindsay. He was a private person who did not seek publicity.

A year and a half ago, he donated $4 million anonymously to the National Trust for Scotland, according to the newspaper The Scotsman. The private organization strives to preserve that country’s heritage by maintaining historic sites such as castles.

Curt DiCamillo, the National Trust’s executive director, told the Scotsman for a story published in today’s edition that Lindsay was the largest donor ever to the group’s American arm.

Thompson said her cousin often would ask her opinion about what he should do with his money. She had no idea he had so much. She figured he meant a few thousand dollars here and there.

Hodge, who is still in the process of figuring out what Lindsay owned and how much it is worth, said Lindsay gave away an estimated $15 million since 1997. Hodge said he believed Lindsay still had millions left.

He said Lindsay once wanted to give money to UNLV, but did not like the bureaucracy he had to wade through to do it.

But Lindsay never showed off his wealth. He lived in a nice house, which he paid $535,000 for in 1998. But he drove an old Lincoln Town Car. He dressed casually. Hodge said Lindsay liked to go shopping and out to eat, but he did not spend his money on art. He filled his house with trinkets, Native American kitsch mostly.

Hodge said Lindsay had no pictures on the walls of his house. He placed a plaque honoring his donation to the Scottish university in his closet.

He remained a mystery, even to his friends.

“He was very much a puzzle,” Hodge said.

And then, last year, Lindsay began to give away some things.

Nobody saw it for what it came to be, but Lindsay appears to have been preparing for the end of his life. He casually remarked to Hodge that he was trying to spend his fortune down.

“He said he was spending down to zero,” Hodge said.

He insisted on signing a do not resuscitate order and wearing a bracelet saying so.

Lindsay gave away a bottle collection to Marvin, 64, his barber. He told Marvin he “wanted to get rid of the dust collectors.”

He also gave Marvin some figurines and two Orange Crush dispensers that had been used in old-time soda fountains.

He brought it all to Marvin’s house on the Saturday before he died.

Marvin said Lindsay often came to his house to watch hockey. Toward the end, Lindsay began to bring Midget along. He remarked one day that he’d like Marvin to take care of Midget whenever he died.

Marvin now believes Lindsay brought the dog along so Midget would get used to Marvin.

And then Lindsay missed an appointment to get his hair cut, which he usually had done every two weeks.

Marvin called Lindsay’s house, but no one answered. He called Hodge, who was about to begin teaching a chemistry class.

Once the class was over, the two met and went to Lindsay’s house. It was early evening by then.

When they went inside, it was clear that something was wrong. Midget refused to come in the house through the doggie door. It was eerily quiet.

They searched, and eventually found Lindsay’s body in the closet. He had obviously been dead for hours.

He had marked the calendar in his house with a dot on each day that passed. The dots stopped on the day before he died, Nov. 16.

His will was simple, a little money to the two cousins and small things for his two good friends. But everything else will go to the National Trust for Scotland, once the trust’s lawyers and Hodge figure out exactly how much there is.

The newspapers over there found out about the donation. Some of them went a little crazy. They called Lindsay a recluse. They made light of the fact that his only real knowledge of Scotland was through the movie “Brigadoon.”

Thompson, his cousin, said Lindsay would never have sought the publicity. He probably wouldn’t have understood the fascination, she said.

“I think he would be astonished.”

Contact reporter Richard Lake at rlake@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0307.