Doctor, nurse describe overcoming Las Vegas shooting challenges

Dr. Kevin Menes had been mentally preparing for victims of a mass casualty event to come through his emergency room doors since his time working at a hospital in Detroit’s roughest neighborhood.

In school, he was taught by the book. People with black tags couldn’t be resuscitated. Gray tags should be left to die. Red tags were critical, but offered the best chance of survival among the three.

But something about that just didn’t sit right with Menes — it was a medieval tactic, he said. During his tenure in Detroit, gray tags survived all the time, as long as someone got them to the hospital fast enough.

So with the right coordination and organization, why couldn’t that happen during a mass casualty event?

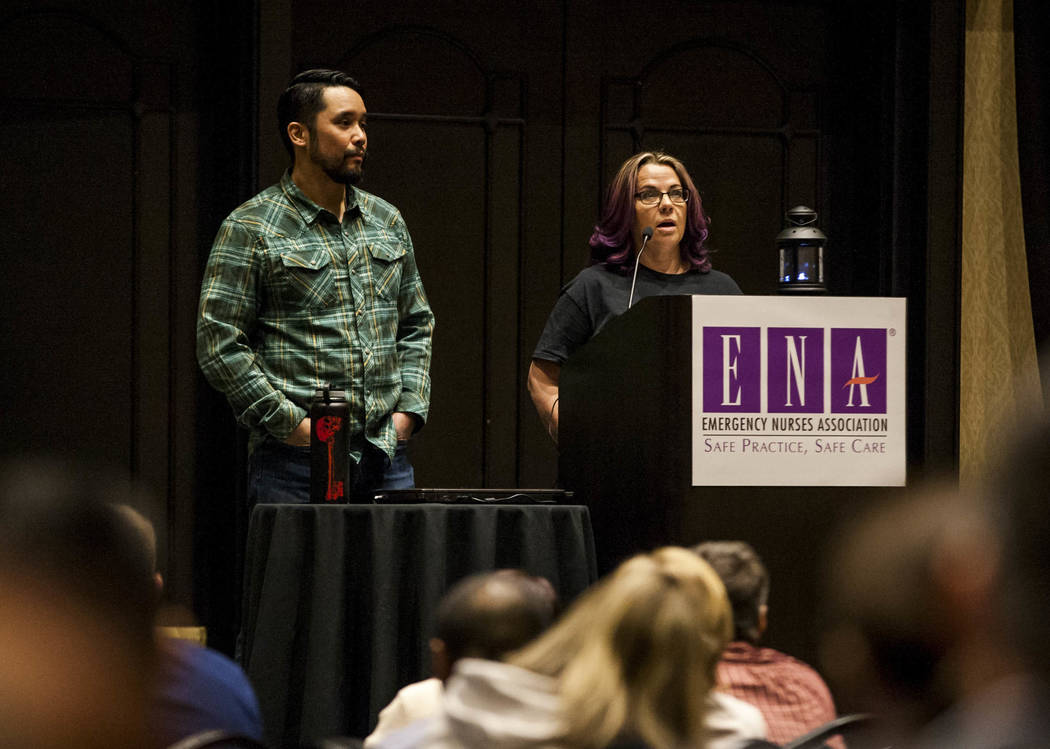

Menes, an emergency physician at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center who took patients in the aftermath of the Oct. 1 shooting on the Las Vegas Strip that killed 58 and wounded hundreds others, gave a keynote speech Thursday at the Emergency Nurses Association’s first regional symposium at Planet Hollywood on how he and his team of clinicians triaged patients and saved hundreds that night.

He was joined on stage by Debbie Bowerman, an emergency nurse who had been joking around with Menes moments before the chaos on Oct. 1.

‘All or nothing’

“I knew that this was sort of ‘all or nothing,’ and so we were going to try this little MCI (mass casualty incident) plan,” Menes told a group of about 200 conference attendees. “And if it didn’t work, I was prepared right at that moment to hand in my badge.”

The first thing he did was clear the operating rooms and emergency room beds. Once patients started flowing in through the ambulance bay, from emergency vehicles and civilian cars, he determined their status and gave them a red, yellow or green tag based on severity.

Everyone was given an IV during triage. If they crashed, having that IV would make resuscitation easier, Menes explained.

And then, patients were moved to a specific station numbered one through four based on the level of care they needed, he said.

“The concept of flow is something that is really important in a mass casualty,” Menes told the crowd. Disorganization could cause delayed care, which could cost a life.

Dealing with difficulties

It could also send critical patients to the wrong area of a hospital, Bowerman explained. A young woman with a brown ponytail reminded her of her daughter. Bowerman, assigned to the ambulance bay to triage patients alone — a big ‘no-no’ in the medical world, but Menes had to leave her to provide care, he explained — left the bay to perform CPR on the woman.

Menes had to tell her to stop. The woman couldn’t be saved. In the meantime, two other patients who showed up at the ambulance bay in Bowerman’s absence were sent to wrong locations within the hospital ER.

“I didn’t understand at the time,” Bowerman said. “Just having to stop and realize you can’t use all your resources the way you do when you’re working on a regular patient was really difficult.”

Other things went wrong. Doctors couldn’t open cabinets containing two general anesthetics, so they had a pharmacist pass them out to clinicians instead. They ran out of chest tubes, and had to hook up two patients to a single ventilator. Pedestrians claiming to be doctors came to the hospital doors with the stench of alcohol on their breath.

Crunched for time and inundated with hundreds of patients, doctors gave up charting to focus on providing care.

But amid the chaos was success.

Menes invited a group of staff members who worked at Sunrise Hospital’s emergency room on Oct. 1 to come up on stage and thanked them for their work.

“They were an integral part to how we ended up pulling this off that night,” he said. “Everybody that came in that night that we could’ve saved, we saved.”

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.