‘Disneyland of poop’: How Las Vegas benefits from wastewater testing

Tucked away on the eastern border of Las Vegas is a dirty secret.

Whenever a toilet is flushed on the Strip or in unincorporated Clark County, the water flows there through a network of 2,200 miles of pipes, where it is treated to a drinkable standard through solid waste removal and biological treatment.

The water recovered — more than 110 million gallons a day — is sent back to Lake Mead via the Las Vegas Wash, allowing Nevada to use more than its very limited annual share of the Colorado River.

“We’re the Disneyland of poop,” said Bud Cranor, a spokesman for the Clark County Water Reclamation District. “The second happiest place on Earth.”

But the massive quantities of water the facility receives don’t only make for a drought solution. They tell a story about Las Vegas that public health officials are just beginning to discover.

By providing the water to outside labs, scientists can quickly detect spikes in disease pathogens such as COVID-19, mpox or influenza. That information is critical for the Southern Nevada Health District, which can issue public health warnings or direct vaccination efforts.

How and when water is collected

The county’s water reclamation district provides daily samples to Verily, a national health company, as well as less frequent ones to local researchers at UNLV and the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

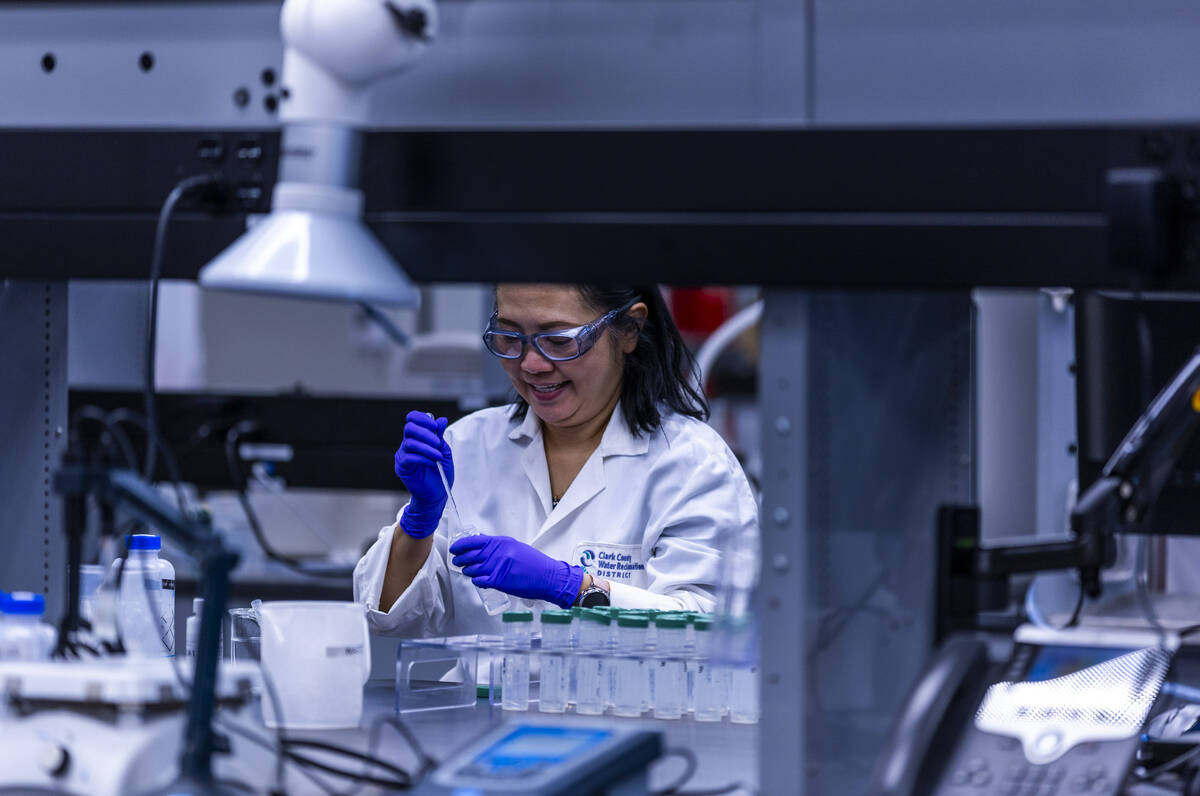

A continuous sample of raw sewage is collected throughout the day. The on-site lab doesn’t currently allow for pathogen testing, though that may be something the district explores in the future.

“That container represents 24 hours of flow into the plant,” said Daniel Fischer, deputy general manager of the water reclamation district. “The computer says, ‘Hey, every 10,000 gallons, suck some of the water up and put it into a container.’ Then, every morning, we come and take the container to analyze it.”

Researchers in Southern Nevada often test sewer systems in different neighborhoods, too, offering a more localized picture.

Dr. Cassius Lockett, the health district’s deputy district health officer of operations, said there have been multiple practical applications of wastewater testing. Most recently, UNLV scientists tested manhole covers around the university and found high levels of mpox, leading the health district to offer a pop-up vaccine clinic in the area.

Testing the water at the reclamation plant circumvents the need to test hundreds of thousands of people on a consistent basis, which is the only way health officials could have previously accessed such a representative sample.

“Wastewater helps us determine how much of a virus might be in the community — high, medium or low — and what public health actions we need to take or relax to keep the community safe,” Lockett said.

There could be some room for better communication between labs and the health district, however, as Nevada law doesn’t currently require wastewater results to be reported to public health agencies, he said.

COVID-19 as a lesson

The idea of broader wastewater testing was spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, said Daniel Gerrity, a principal research scientist at the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

When Verily began conducting daily testing through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Wastewater Surveillance System and WastewaterSCAN, Gerrity and other researchers could focus in on specific studies and more localized testing in community sewers, such as one effort that showed illicit party drugs in higher concentrations after a music festival.

“Wastewater surveillance is really effective, and it’s not something that has been used broadly in public health before,” Gerrity said. “But we think it’s a great complement to what we’re doing with traditional surveillance.”

Amy Lockwood, Verily’s public health partnership lead, said Las Vegas’ testing is an example of how the private sector can partner with the public sector for the greater good.

The company ramped up its testing for a HLTH health care conference at The Venetian this week in an effort to show attendees how wastewater testing can be useful.

While there’s been a lot of engagement with testing after the COVID-19 pandemic, Lockwood said finding a reliable and constant funding stream remains a challenge.

“It’s the kind of thing that we tend to — in the United States and elsewhere — fund when there’s a problem and not fund when there isn’t a problem,” Lockwood said. “That’s not how surveillance works, so it’s a constant challenge to be advocating for the benefit of this, even if we’re not finding something bad today.”

Some wastewater pathogen testing may one day happen on-site at the reclamation district’s lab rather than through labs like Verily, though finding financial support and worker expertise is a barrier, officials said.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.