Desert tortoises looking for homes in Nevada

A small group is having a shell of a time trying to find homes for the Nevada state reptile.

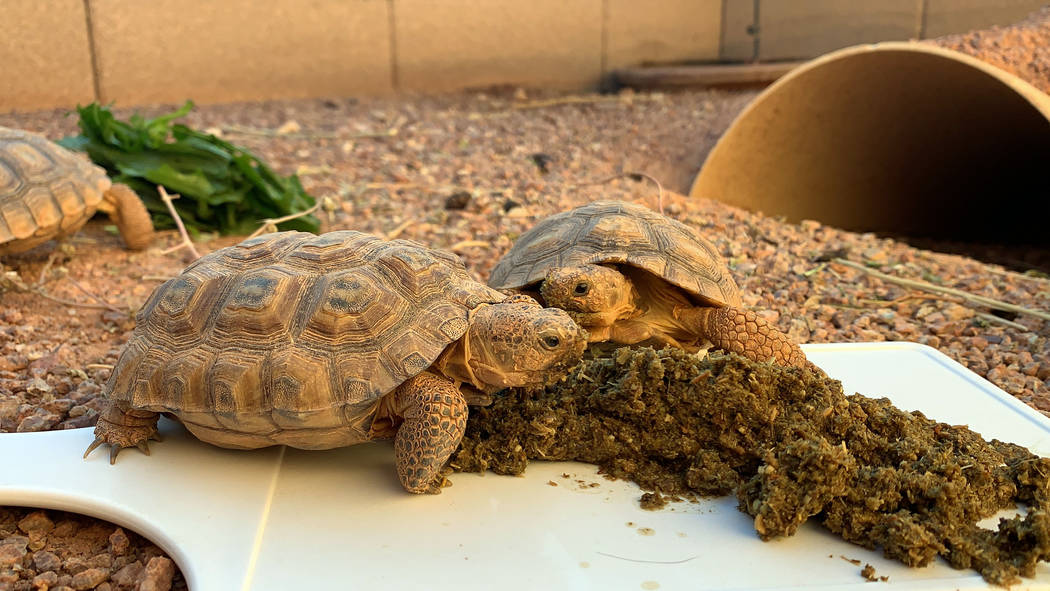

The desert tortoise has resided on the endangered species list since 1989 as its numbers in the wild dwindled due to habitat encroachment and other forms of human interference. Yet, the species faces a very different problem in captivity: overpopulation.

So says the Tortoise Group, which works to address the problem by providing its namesake homes throughout Nevada. The group’s executive director, Kobbe Shaw, said there is a misconception that it is illegal to keep a pet desert tortoise in Nevada. It’s not, although the group represents the state’s sole legal avenue of adoption, according to Ashley Sanchez, spokeswoman for the Nevada Department of Wildlife.

Confusion over legality remains among the public, however, and that can lead some to be hush-hush about the tortoise sun-bathing in their backyard, Shaw said.

“The first rule of tortoise club is you don’t talk about tortoise club,” Shaw said.

Shaw, citing in part a 2018 UNLV study of the species, estimated there are roughly 150,000 and 180,000 captive tortoises in Clark County. He thinks there are nearly as many local captive tortoises as there are in the wild.

Fish and Wildlife Service tortoise biologist Flo Deffner cautioned it was hard to estimate the number of wild tortoises because it’s not a homogeneous spread across the desert.

But as Las Vegas has “exploded” over the last couple decades, so has the captive tortoise population, and it’s enough to warrant concern, Deffner said.

The UNLV tortoise survey indicates there are valley neighborhoods with higher concentrations of tortoises than others, particularly in the southwest and northwest. This gives the Tortoise Group — which also runs a popular health clinic, performs outreach and partners with other organizations to protect them in captivity and in the wild — a better sense of where to target their efforts and message.

“People just breed tortoises and give them to their neighbors,” Deffner said.

And introducing captive tortoises to the wild can spread disease or cause other problems to the species. As a result, many of those captive tortoises are in need of a home away from home.

Shaw said the nonprofit averages about 1,500 requests per year of unwanted tortoises with roughly two tortoises per request. With help from a handful of volunteers, the two-employee nonprofit cares for its tortoises at a private yard in the northwest valley. They’re usually at capacity with about 65 to 70 animals and are always looking for custodians.

“Easiest pets in the world to take care of,” Shaw said. “They sleep six months out of the year. If you want to go on vacation, you don’t have to worry about feeding them every single day.”

Does a poky pet peak your interest? Visit the nonprofit’s website at http://tortoisegroup.org/ for more information on adoption and additional specifics on tortoise care.

In the meantime, here are some things to keep in mind if you’re looking to carve out a place in your yard and heart for a cold-blooded friend.

You’re not its owner

Technically, anyway. State law dictates that any desert tortoise, wild or captive, is considered wildlife and therefore belongs to the people of Nevada. Accordingly, those who keep a tortoise as a pet are considered its custodians and not owners.

It’s legal to have a tortoise if it was acquired before Aug. 4, 1989, when the species gained its protected status, if it’s progeny of such a tortoise or if you adopt it through the Tortoise Group program.

The Fish and Wildlife Service didn’t want to criminalize tortoise owners when it decided to list the species as in need of protection, so it grandfathered in legal captivity for people who already had them, said Deffner. Now, the service provides grant money to and authorizes the Tortoise Group to adopt out the reptiles.

A new custodian may adopt only one tortoise per custodian to avoid the risk of breeding and feed into the captive overpopulation problem, said Shaw, who heads the Tortoise Group.

Yes, the species is threatened, but custodians who breed their captive tortoises cause more problems than they solve, said Sarah Mortimer, the group’s biologist.

“They’re breeding these animals in their backyard thinking they’re contributing to conservation effort, but it’s the exact opposite in that case because those tortoises can’t be used to recover the wild population,” she said.

Keep in mind that your tortoise will probably outlive you: they can survive 80 to 100 years in captivity. You should be prepared to provide a forever home for a forever pet, as releasing it into the wild could prove a death sentence for the animal.

“People just throwing them out in the desert, especially this time of year,” Mortimer said, “they probably are overheating before they could even dig a burrow.”

Diet, diet, diet

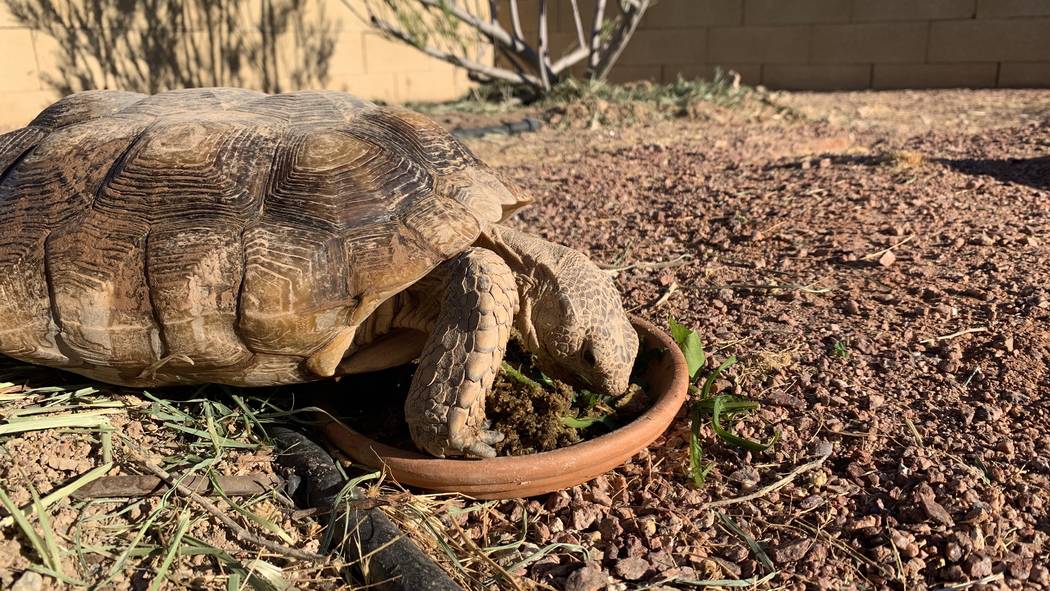

Just because your tortoise might enjoy munching on a strawberry or sprig of lettuce doesn’t mean it should. Mortimer cautioned custodians to maintain a strict diet of specially formulated tortoise food (the group recommends Grassland Tortoise Food) and plants found in their natural environment like spineless cacti, primrose or globe mallow. Fruits and frozen vegetables can be harmful to your tortoise.

“If it grows in the Mojave Desert, it’s what a tortoise eats,” adds Shaw.

Custodians will spend roughly $50 to $75 per year in food, he estimated. Otherwise, your tortoise should be content to pick at grasses and ornamental in its enclosure.

Sick of the dandelions in your yard? Your tortoise will happily (and healthily) chomp them up.

In terms of watering, your tortoise can likely go a couple of weeks without it — it is a desert tortoise, after all — but one watering per week should suffice, Shaw said.

Habitat

A 600-square foot enclosure in a “postage stamp Las Vegas backyard” will suit your reptile well, Shaw said. Your whole backyard can be its enclosure, too, as long as it’s got proper barriers to prevent it from escaping and harming itself.

Sprinkle in some plants for shade and snacking and then dig a burrow, where it’ll spend most of its time avoiding the heat or brumating away the cooler months.

Brumation, the reptile version of hibernation, lasts about six months out of the year until they reemerge in the spring.

The Tortoise Group will discuss with prospective custodians on how best to create a habitat and burrow suited for each, he said.

Contact Mike Shoro at mshoro@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290. Follow @mike_shoro on Twitter.