Clues reveal few hints about fate of missing soldier

His family doesn’t know whether he died in uniform from injury or illness, or from an unexplained incident in France at the end of World War II. But one thing is certain: Roman G. Padilla risked his life for his country and died for it too.

"Every step I take may cost me my life so I decided I’d write you a nice long letter cause it may be the last one," Padilla wrote in a 3-foot-long letter penned in black ink on government-issued toilet paper.

"I’m not even allowed to tell you all the dead people I’ve seen but I can tell you that we are camped in an area about an acre square and in that area there must be at least 50 dead Germans," reads the letter to his sister, Frances Salazar, dated Aug. 18, 1944, from "somewhere in France."

Gina Greisen of Las Vegas said her grandmother "really, really loved her little brother. There was intense fear for losing him. I don’t think she ever got over him dying."

Padilla, an Army "Tec 5" specialist, had just turned 20 when he wrote the letter "on toilet paper cause I have no other kind and please don’t send none cause it’s just more junk I have to carry around."

"Tell the old man he ought to be here with me. There is plenty of wine around here.

"Yesterday, the boys found 2 (two) 50 gallon barrels of it in a bombed home and according to them it’s good stuff. It’s a good thing I never touch the stuff but I probably will before long being that there’s no beer around here."

Sixty years ago on Memorial Day – May 30, 1952 – Padilla’s name and the names of dozens of other Nevadans who died in World War I, World War II and the conflict in Korea were unveiled on a monument erected by the Desert Chapter American Gold Star Mothers of Las Vegas.

Etched tenth from the bottom of the center panel on a black granite slab, his name has weathered with time. The slab stands beside a white stone monolith that juts from the lawn at the southwest corner of Bonanza Road and Las Vegas Boulevard.

Despite the monument’s clear message, "Lest We Forget," the story about what Padilla did in the war and why he’s listed as a nonbattle death vanished when his divorced parents took those secrets to their graves.

Greisen and her cousin, Joe Salazar, a Clark County firefighter, sought answers to their great-uncle’s death.

In 1997, Joe Salazar made a trip to Draguignan in southern France, where Padilla is buried along with 860 soldiers and Marines at the Rhone American Cemetery and Memorial.

Salazar said the trip was important to give closure to the family and especially his grandmother, because "nobody had been to visit and put flowers on his grave."

The trip also turned up a clue about Padilla’s role in the war. In addition to the date of his death, Sept. 27, 1945, the white cross headstone that stands in an open area surrounded by cypress, olive and oleander trees, contains initials for his rank, unit and state: "Tec 5 732 Ry Operating Bn Nevada."

That means when he died, he was a technician fifth grade assigned to the 732nd Railway Operating Battalion. It was one of the units that rebuilt bombed-out rail lines and bridges so trains could deliver equipment, gasoline and supplies to Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army as it swept across northeastern France and Belgium to drive Nazi forces back to Germany.

About a year before Frances Salazar died in 2003, the family surprised her on her birthday with a framed collection of photographs of Padilla, the soldier, and that cherished memento, the toilet paper letter.

Today the collection hangs on the wall at the Las Vegas home of Ray Salazar, Joe’s father. Ray Salazar also has a wooden-handled Nazi dagger that was shipped home after the war with his uncle’s personal belongings. The steel blade is stamped with the words, "Ulles fur Deutchland," or "All for Germany."

Ray Salazar also has some of Padilla’s letters written on Army stationery that give hints that his military occupation carried over from what he did in civilian life. He worked with his brothers at their family-owned restaurant, El Gorditos on Fremont Street.

One letter mentions the "Jeep-in Cafe," the name he gave to their portable mess hall. He complained about running out of eggs to feed the troops.

"Sometimes they bring their own eggs and meat to us and we cook it for them," Padilla wrote on Aug. 24, 1944.

"Well, Sis, the time is now 4:30 in the morning and I’m getting sleepy so I’ll finish now and start slicing bacon for morning so that I won’t fall asleep. So long and good luck to you all and please don’t worry about me.

"I’m no baby and I can take care of myself at last. I’ve done it for 6 or 7 years, and I still consider myself man enough to do so."

But one thing didn’t jibe with the unit reference on his headstone marker. In one photo, Padilla with his boyish face and neatly combed, dark brown hair is holding an M1 carbine. The shoulder patch on his olive-drab uniform is a red-trimmed white circle with a blue star in the middle, the unit patch for the 718th Railway Operating Battalion.

As Greisen learned this month from reading a 100-page narrative written by the chaplain for the 718th Railway Battalion, her great-uncle wasn’t the tip of the spear, but the part that helped Patton throw it at the Nazis in the Battle of the Bulge.

The 718th railway team landed at Utah Beach in Normandy on Aug. 15, 1944, about two months after the D-Day invasion of France and three days before Padilla penned the toilet-paper letter.

"The 718th was selected to serve the railheads of the Third Army, then engaged in the drive on Metz. … The 718th consistently and diligently hurried supplies to the Third Army railheads," reads the narrative by Capt. Floyd R. Williams, chaplain and battalion historian.

Based on the dates in the narrative, Padilla probably wrote the toilet paper letter in an orchard at Folligny, near the coast in northwestern France where the 718th built shanties from wood scraps in the orchard and cooked on stoves that the Germans had left behind. That’s where they saw the first casualties, German bodies, as Williams described them.

Rebuilding the railroad was a daunting task, because it had been bombed and demolished by both Allied and Axis forces.

"The scene presented was one of perfect destruction, the result of a smashing American advance and demolition by withdrawing Germans," Williams wrote.

After a month’s work rebuilding rails and refurbishing engines, the 718th moved into the thick of battle, arriving at Bar-le-Duc in northeastern France and on to Sezanne.

On Oct. 7, 1944, the 718th endured seven hours of artillery bombardment and experienced its first casualty when a soldier was killed in a rear-end collision of French trains.

At Bar-le-Duc, the battalion kept busy running prisoner-of-war trains from the front and sending hospital trains to the front.

On Dec. 4, 1944, less than two weeks before the Battle of the Bulge began, the battalion encountered almost continuous strafing at night, "however supplies rolled on to the Third Army," Williams wrote.

"During December the Germans opened their famous counterattack through Luxemburg and Belgium into territory operated by the 718th. The shifting of the Third Army from the Metz front to the north to meet the German threat was a noteworthy achievement in military history, and it fell upon the 718th to play an important role in moving supplies and equipment by rail from one sector to another."

On Jan. 10, 1945, Sgt. Joseph Cushman of Company C died "in a spectacular train accident" when its ammunition cargo exploded.

As the battalion moved north to Gouvy, Belgium, crews had to replace 27 bridges before the line could operate and pass through 18 tunnels.

"For some unknown reason the enemy demolished the bridges but left the tunnels intact," Williams wrote, adding, "Hazards from mines, bombs, artillery became a daily diet for the detachment."

One day, the unit accomplished a "Herculean task" by shuttling 18,000 prisoners from the front.

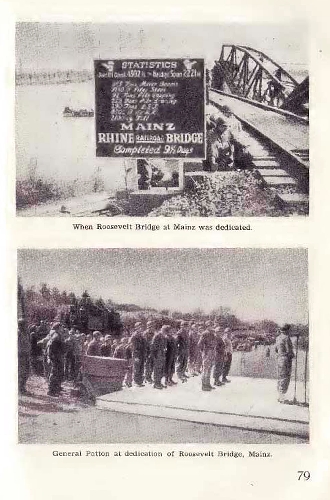

Then in April 1945, the battalion worked with the 347th Engineers to build a single track bridge over the Rhine River at Mainz, Germany. The Roosevelt Bridge, named in honor of the late President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was completed in 9½ days and dedicated in person by Patton, who made the first trip across it with the 718th.

"Padilla, Roman G. Tec 5," is listed on the May 9, 1945, V-E Day roster for Headquarters Company of the 718th Railway Operating Battalion, but what happened during the next four months is unclear.

At some point, Padilla was assigned to the 732nd Railway Operating Battalion and sent to southern France near Marseille where he was put in a hospital at Saint-Victoret on Sept. 23, 1945. He died four days later, according to morning reports.

Seven years later, one of Padilla’s comrades, James H. Casey, wrote his parents, explaining that he and 19 others were sent to Marseille, France, "for the purpose of filling the roster of an outfit to the Pacific Theatre."

"We were in the staging area there when the war in the Pacific ended and our orders were cancelled just before time to board ship. This was very disheartening to all of us because we were sure that if we got aboard ship and got started, we stood a good chance of being sent home," according to Casey’s Sept. 12, 1952, letter to Greisen’s grandmother.

As a result, Greisen’s great-uncle never came home from the war. She hopes the National Archives and Records Administration can find his records. Some might have been lost in the 1973 fire at the records center in St. Louis.

But she will always know that Roman G. Padilla was a soldier and a gentleman.

"I knew him only as a soldier," Casey wrote. "But having known him so, I can assure you that he was always a true friend and a gentleman in every respect, and I know you take great pride in having played a great part in making him the man that he was.

"His untimely death was a terrible shock to me and all who knew him."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.