He designed affordable bungalows for first-time homeowners and luxurious mansions for Southern California’s elite, though as a Black man he wouldn’t have been allowed to live in some of the neighborhoods where those mansions were built.

Architect Paul Revere Williams also designed some notable Las Vegas buildings and contributed to the valley’s historical landscape by creating homes for middle-class Black residents in the Historic Westside and Black workers in Henderson.

Now 41 years after his death, Williams may not be a household name, but many of the homes, churches and other buildings he designed stand as testament to his impact here and in Southern California.

“He was a trailblazer in the architecture community,” said Dave Cornoyer, who has researched and written about Williams’ work in Las Vegas. He created “a very diverse collection of buildings and really thoughtful plans that are far ahead of (his) time.”

Early adversity

Williams was born in Los Angeles in 1894 and lost both of his parents to tuberculosis by the time he was 4, said Leslie Luebbers, project director of The Paul R. Williams Project (paulrwilliamsproject.org), a collaboration of the University of Memphis, the Memphis chapter of the American Institute of Architects and the National Organization of Minority Architects.

He was taken in by a woman who was “variously called his foster mother or adoptive mother. It’s not clear what the relationship was,” Luebbers said. “But they were very devoted to his education.”

He was the only Black student in his elementary school, Luebbers said. In an essay, “I Am a Negro,” published in American Magazine in 1937, Williams wrote that, as a child, he “played with white children without being conscious of the stigma attached to color.

“Nothing prepared me for the shock of the discovery that someday those children who then accepted me as one of themselves would learn to treat me with a strange admixture of patronage and contempt, intolerance and condescension. There was nothing to warn me that coveted opportunities would be denied me because my face was black.”

Construction of La Concha Motel in Las Vegas designed by architect Paul Revere Williams. (Nevada State Museum)

Construction of La Concha Motel in Las Vegas designed by architect Paul Revere Williams. (Nevada State Museum)  La Concha Motel in Las Vegas designed by architect Paul Revere Williams. (Nevada State Museum)

La Concha Motel in Las Vegas designed by architect Paul Revere Williams. (Nevada State Museum) Designing a career

Williams recalled that even as a child he had “an instinctive interest in the design of buildings” and decided to become an architect while in high school. But when he told his teacher of his plans, “he stared at me with as much astonishment as he would have displayed had I proposed a rocket flight to Mars. ‘Who ever heard of a Negro being an architect?’ he demanded.”

Williams worked his way through university and got a job as a draftsman. Along the way, he “won several national awards for design that brought him to the attention of people,” Luebbers said. “So he sort of interned, but he was basically so good he actually got paid to work for a number of very high-profile architecture and engineering (firms).”

By his early 20s, Williams had opened his own firm, cultivating a mostly Southern California-based practice designing small, efficient homes for average people, mansions for Hollywood stars, churches and public buildings, and became “enormously successful,” Luebbers said.

He was a wealthy man. His power within the (Southern California) Black community was very strong, and he did a lot of pro bono buildings for the community. He was very generous and contributed to Black causes.

Leslie Luebbers, project director of The Paul R. Williams Project

“He was a wealthy man. His power within the (Southern California) Black community was very strong, and he did a lot of pro bono buildings for the community. He was very generous and contributed to Black causes.”

Yet Williams wrote that he also “encountered many discouragements and rebuffs, most of which were predicated upon my color.”

When potential clients who didn’t know that he was Black walked into his office, most “were obviously serious in their intention to build. Yet in the moment that they met me and discovered they were dealing with a Negro, I could see many of them ‘freeze.’ Their interest in discussing plans waned instantly, and their one remaining concern was to discover a convenient exit without hurting my feelings.”

“Virtually everything pertaining to my professional life, during those early years, was influenced by my need to offset racial prejudice,” Williams wrote, while the “weight of my racial handicap forced me, willy-nilly, to develop salesmanship.”

For example, Williams learned to draw upside-down so that a prospective client sitting across the desk could see his home appear on paper before his eyes, becoming, Williams explained, “a full partner in the birth of that room.”

The tactic also addressed white clients’ reluctance to sit next to him. “Obviously, Mr. Williams was very adaptable and had to be because of the way society was at the time,” Cornoyer said.

Coming to Las Vegas

During World War II, Williams was hired to design temporary housing for African American workers at Basic Magnesium Inc. in what would become Henderson. Williams designed 498 units and a dormitory in a development called Carver Park, Cornoyer said.

Carver Park “really starts the city of Henderson,” said Claytee D. White, director of the Oral History Research Center at UNLV Libraries. “It was one of the main reasons Blacks migrated there during that era, a lot of them from Fordyce, Arkansas, and Tallulah, Louisiana.”

Williams’ next housing development here was Berkley Square, in Las Vegas’ Historic Westside, which opened in 1955. Laws then “restricted where African Americans could buy homes,” Cornoyer said. “Berkley Square was the first (development) where African Americans could buy a new house.”

Sculptures line the walls of Guardian Angel Cathedral, designed by renowned African-American architect Paul Revere William, on Friday, Feb. 5, 2021, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto

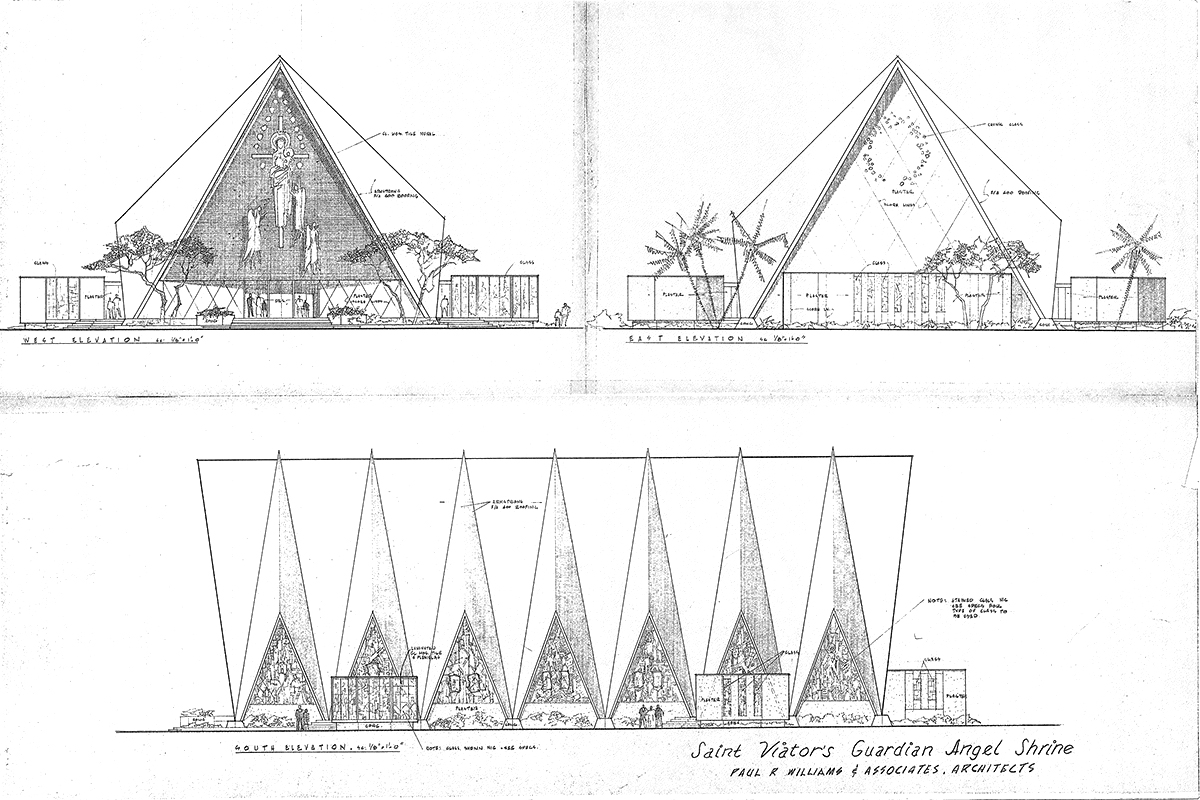

Sculptures line the walls of Guardian Angel Cathedral, designed by renowned African-American architect Paul Revere William, on Friday, Feb. 5, 2021, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto  Plans for what then was being called St. Viator's Guardian Angel Shrine bear the name of Paul R. Williams' firm.

Plans for what then was being called St. Viator's Guardian Angel Shrine bear the name of Paul R. Williams' firm.(Courtesy of the Guardian Angel Cathedral, Diocese of Las Vegas)

Berkley Square’s opening coincided with the opening of the Moulin Rouge, Las Vegas’ only integrated resort, White noted. “So we have a lot of (African American) people coming to the city. The vibrancy of the Black community is really evident at this time. They’re hiring dancers to dance at the Moulin Rouge. They’re hiring people to be chefs and waiters and dealers. And at the same time, we have housing being constructed where these people can live.”

Berkley Square was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. Ruth Eppenger-Dhondt grew up there and now lives in the home next door to her family home, which her parents bought in 1957. She remembers Berkley Square then as a community mostly of working families. “Families knew each other there. It was very social.”

Williams’ original floor plans included a back yard and a carport. Eppenger-Dhondt said most of Berkley Square’s homes have been altered over the years, but Williams seems to have designed them with middle-class homeowners in mind.

“I think his talent gave him insight into what was needed,” she said.

A Vegas portfolio

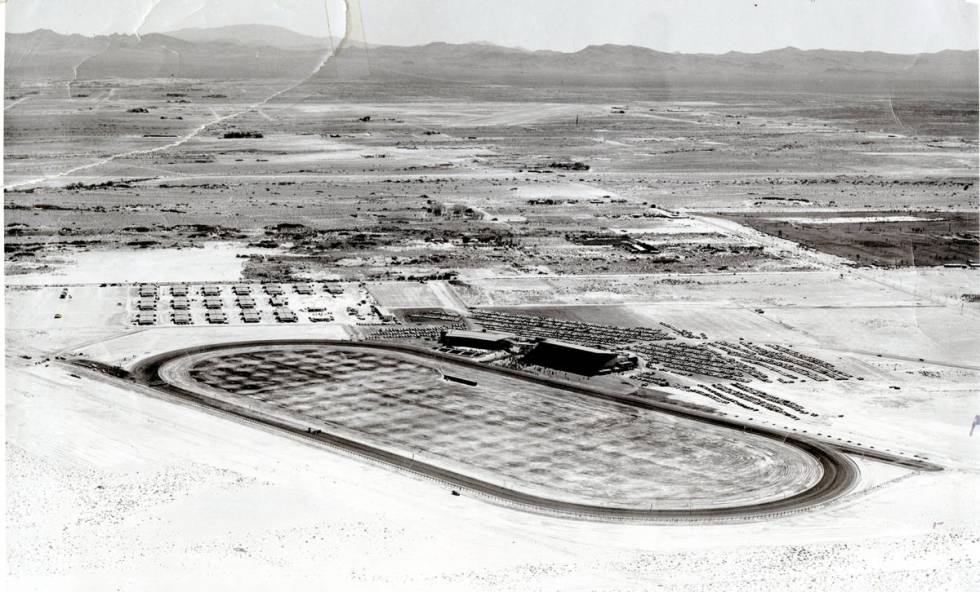

Williams continued designing for Las Vegas through the 1960s in projects that demonstrated an amazing versatility. Las Vegas Park, a horse racing track on Paradise Road, in the vicinity of the Westgate and Las Vegas Country Club, for which Williams designed the Jockey Club, opened in 1953 but didn’t last. He designed the SkyLift Magi-Cab, a never-realized monorail for the Strip, in 1966. And he designed the Royal Nevada Hotel on the Strip, which opened in 1955 but became part of the Stardust in 1959.

One of his most striking Las Vegas buildings was the La Concha Motel, which opened in 1961. Situated on the Strip across from Circus Circus, the motel’s futuristic lobby was used for more than 40 years and now serves as the visitor center for The Neon Museum.

When the former La Concha Motel lobby was repurposed as The Neon Museum’s visitor center, Dawn Merritt didn’t need customer surveys to tell whether visitors liked it.

The only metric needed was seeing how many guests would trip while walking up the building’s steps because they were too busy staring at it or photographing it as they entered.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the La Concha Motel, which opened in 1961 on the Strip. Designed by Black architect Paul Revere Williams, the motel’s lobby building was moved in 2006 to the Neon Museum, where it now serves as a sign itself.

“We don’t have a sign … that says ‘Neon Museum’ ” said Merritt, the museum’s vice president and chief marketing officer. “That building s our biggest sign.

“It reminds me of ‘The Jetsons.’ I love it because it’s also nostalgic.”

Effective, too. “Once, we did have someone who wanted to check in,” she said. “We had to explain we’re not a hotel.”

The interior of the The Neon Museum, formerly the La Concha hotel lobby, in Las Vegas, on Tuesday, Feb. 9, 2021. Architect Paul R. Williams designed was the original designer of the hotel lobby. (Erik Verduzco / Las Vegas Review-Journal) @Erik_Verduzco

The interior of the The Neon Museum, formerly the La Concha hotel lobby, in Las Vegas, on Tuesday, Feb. 9, 2021. Architect Paul R. Williams designed was the original designer of the hotel lobby. (Erik Verduzco / Las Vegas Review-Journal) @Erik_VerduzcoThe Neon Museum’s collection includes several signs that celebrate Las Vegas’ African-American history. According to the museum — and with historical information from the late Dorothy Wright, a long-time museum board member and early architect of the museum — the collection includes these signs:

The Moulin Rouge: Las Vegas’ first integrated resort and the location of a March 1960 meeting of community leaders that helped to lead to the end of segregation in Las Vegas hotels and casinos. In addition, Sarann Knight-Preddy, the first Black woman in Nevada to receive a gaming license, owned the Moulin Rouge for several years. (The Moulin Rouge sign last year was reassembled and re-illuminated and now is in the museum’s Neon Boneyard.)

The Silver Slipper: The site of a 1950s local NAACP program for Black History Month during a time when, according to the museum, it was almost impossible to rent a room for a Black event in a Strip or downtown casino. (There are two signs, one near the La Concha visitor center and another in the Neon Boneyard.)

Fitzgeralds Hotel and Casino: Owned by Don Barden, one of just a few African-American casino owners in the country. (The sign is in the Neon Boneyard)

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.

The La Concha demonstrates that Williams “wasn’t averse to any kind of architecture,” said Mark Hall-Patton, Clark County museums administrator. “He wasn’t tied down to a style, he wasn’t tied down to an era, he wasn’t tied down to anything.”

The Williams-designed Guardian Angel Cathedral — originally called St. Viator Guardian Angel Shrine — opened on the Strip in 1963. The modernistic A-frame design is a departure from the more traditional church buildings he designed in California, and the church is still in use after being renovated in 1995.

Unwelcome welcome

According to Luebbers, Williams found that Las Vegas “wasn’t as friendly” as Southern California or cities back East where he also did business.

Las Vegas “was populated later than Los Angeles, and a lot of people who came there were from the South,” she said. “So when he was in Las Vegas or Reno, there was no place he could stay. He couldn’t stay in a hotel, he couldn’t eat in a restaurant.”

The 1937 magazine essay is “the only thing he ever wrote that sounds a little angry, but very eloquent,” Luebbers said. “He never did that again because there was a lot of backlash — strangely, mostly among Black readers.”

Carver Park. (Courtesy Clark County Museum)

Carver Park. (Courtesy Clark County Museum)  A view of the home of Ruth Eppenger-D'Hondt in the Berkley Square neighborhood, which was designed by architect Paul R. Williams, in Las Vegas on Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto

A view of the home of Ruth Eppenger-D'Hondt in the Berkley Square neighborhood, which was designed by architect Paul R. Williams, in Las Vegas on Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto Legacy

Williams designed thousands of homes and commercial buildings before his death in 1980 at age 85. He is considered the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects, Cornoyer said, and in 2017 was awarded the AIA’s Gold Medal.

Defining Williams’ legacy in Las Vegas is difficult because his work here was “so diverse,” Cornoyer said. But Williams’ significance here rippled beyond the structures he created, said Esther Langston, an emeritus professor at UNLV who lived in Berkley Square from 1963 to 1968.

Berkley Square “became a family where we all knew each other, we all helped each other, we socialized together. Our kids grew up there,” she said.

“What (Williams) really developed in Las Vegas was a sense of community and family. He was building a community.”

Paul Revere Williams’ work in Southern Nevada took place from the early ’40s through the ’60s., said Dave Cornoyer, who has researched the architect’s work in Las Vegas.

Carver Park, designed as temporary housing for Black workers at Basic Magnesium Inc. in what would later become Henderson. The development, located at Lake Mead Drive, had 498 one-, two- and three-bedroom units and a large dormitory, Cornoyer said. In 1974, all but one building was demolished.

Las Vegas Park, a horse racing track, opens on Paradise Road. Williams designed the track’s Jockey Club. Horse racing never caught on here , Cornoyer notes, and the land was sold, eventually becoming the site of Las Vegas Country Club and what is now the Westgate.

Berkley Square in Las Vegas’ Historic Westside opens. According to Cornoyer, Planning began in 1947 for the 148-home community eventually named after primary project financier Thomas Berkley, an Oakland businessman, attorney and civil rights advocate. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

The Royal Nevada Hotel opens on the Strip, adjacent to the Stardust. According to Cornoyer, It soon fell into bankruptcy and in 1959 was absorbed into the Stardust.

The La Concha Motel, a 100-room motel designed by Williams, opens. Located on the Strip across from Circus Circus, the motel’s dramatic lobby operated on the Strip for more than 40 years, Cornoyer said. In 2006, it was relocated to become and became the Neon Museum’s visitor center.

St. Viator Guardian Angel Shrine, with Williams’ modernistic, A-frame design, opens on the Strip. Now called Guardian Angel Cathedral, the building underwent a renovation in 1995.

Williams designs the SkyLift Magi-Cab, a monorail system proposed for Las Vegas. According to The Paul Revere Williams Project, the system would have had cars traveling from McCarran International Airport to 15 stations.

Sources: Dave Cornoyer and research

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.