Las Vegas’ courtyard for the homeless experiencing growing pains

Six months after it began operating around the clock, the city of Las Vegas’ homeless courtyard is experiencing some serious growing pains.

The main contractor hired to manage the courtyard — a single fenced-in complex where the homeless can sleep and access a range of services — had its $2.1 million contract with the city terminated Oct. 31 amid controversy and complaints, according to city emails obtained by the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

Then on Friday, a social worker who had effectively been managing day-to-day operations at the courtyard after the departure of the original operator, said he resigned from his position after being informed his job was “on the line” primarily because of a dispute over overdue payments to subcontractors.

“This is a harpoon. I think this is a scapegoat mentality,” Kevin Whalen told the Review-Journal, referring to what he said was his imminent firing.

Efforts to reach a city official in charge of the program on Saturday were unsuccessful. City spokesman Jace Radke said that he could not confirm Whalen’s departure.

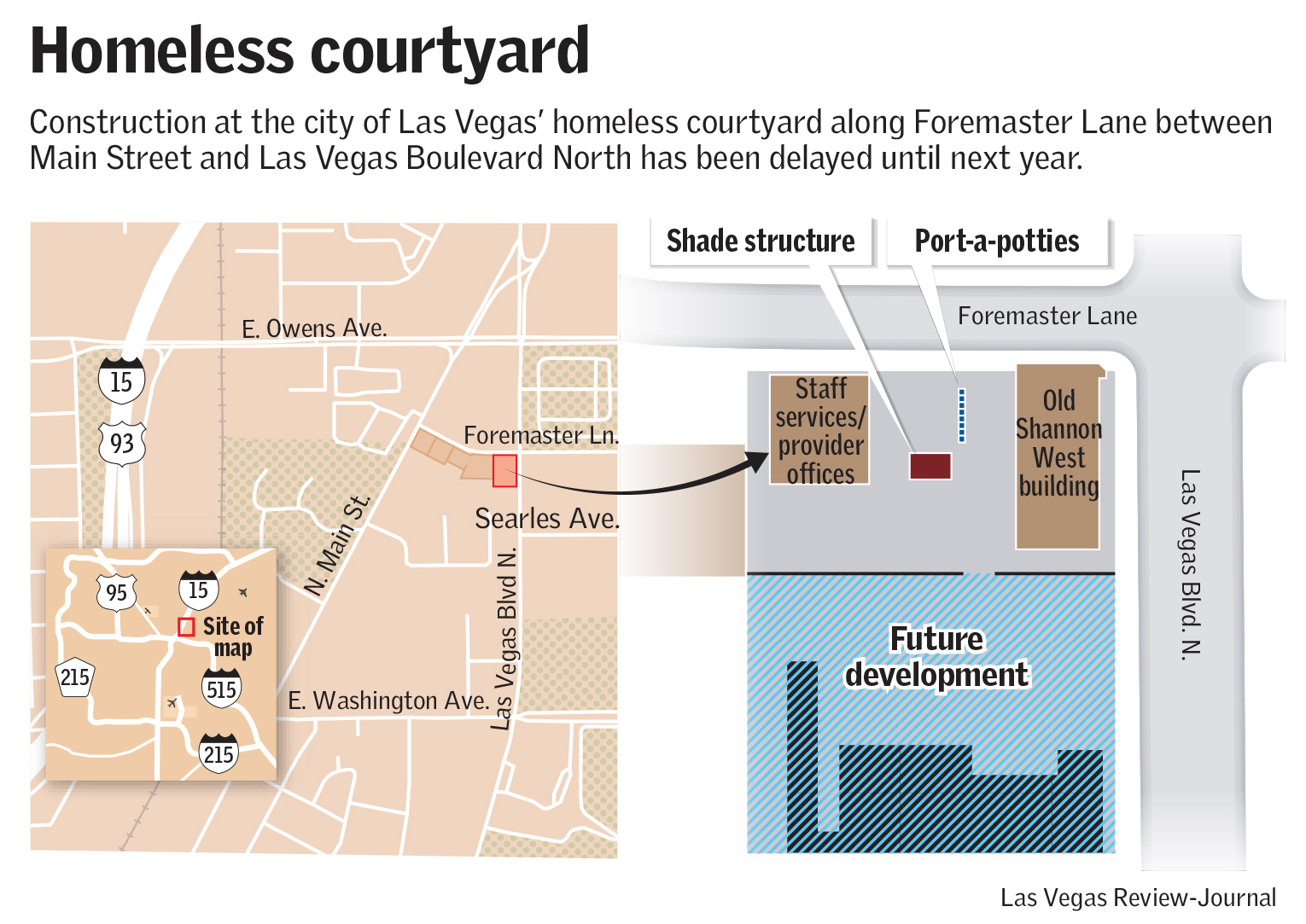

Meanwhile, the buildout of the courtyard to include more infrastructure, funded by more than $16 million in grants and bond proceeds, has been delayed until next year.

Adding to the apprehension are questions about efforts to raise private money to help subsidize the cost of the courtyard, which Mayor Carolyn Goodman has said cannot be sustained by the city alone.

The problems have left some service providers concerned about the future of the project intended to guide the homeless off the streets and into permanent shelters and jobs. And other nonprofits worry about the possible impact on the existing safety net for the homeless.

“We know it takes time to build new buildings,” said Deacon Thomas Roberts, head of the longtime local homeless service provider Catholic Charities of Southern Nevada, which sits directly across from the courtyard at Foremaster Lane and Las Vegas Boulevard North in an area labeled the “Corridor of Hope” by the city. “… But it does make sense to be thoughtful in a way that’s consistent with their collaboration with us. It’s early, but we’re obviously affected by everything that happens in the corridor.”

The city allocated nearly $2.5 million for courtyard operations for the fiscal year that will end June 30. Drafting of the budget for the next fiscal year has yet to start, but city officials say they do not anticipate any retreat from the concept, despite the current difficulties.

“We anticipate being funded every year that we operate. It’s just a matter of how,” said Jocelyn Bluitt-Fisher, the city’s community services administrator who oversees the courtyard’s operations. “The city is always funding it. This is our project, and we’re fully committed.”

And Whalen said that despite the recent turmoil, the courtyard is helping people access services.

“There’s a lot going on there, and there’s a lot of good happening,” he said. “People are getting help, that’s the bottom line.”

‘Trial period’

The homeless courtyard operated part time for more than a year before opening as a 24/7 facility in July, several months after its planned launch in March.

The nonprofit Southern Nevada Community Health Improvement Program, known as CHIPs, won the contract to run the facility only to leave at the end of October after receiving nearly $48,500 from the city to exit the contract.

Bluitt-Fisher said such course corrections were not unexpected.

“It’s a trial period, period. This is a new endeavor, never done here before in Southern Nevada,” she said. “We all came in with good intentions and wanting to do our best, and we just determined that this wasn’t something that was working for either of us.”

She said the vision for the courtyard remains intact, and the transition to hiring staff from a temporary agency to replace the CHIPs employees has been “seamless.”

Alexandria Anderson, executive director of CHIPs, said she doesn’t regret the short-lived partnership with the city.

“It was a great opportunity for us to have ears to the street and learn what was going on,” she said. “I wish it all the success.”

But Anderson said communication breakdowns and expectations that weren’t spelled out in CHIPs’ contract with the city led to the termination.

“I’m just not sure we were clear on what the city wanted from us,” she said.

Conflict among providers

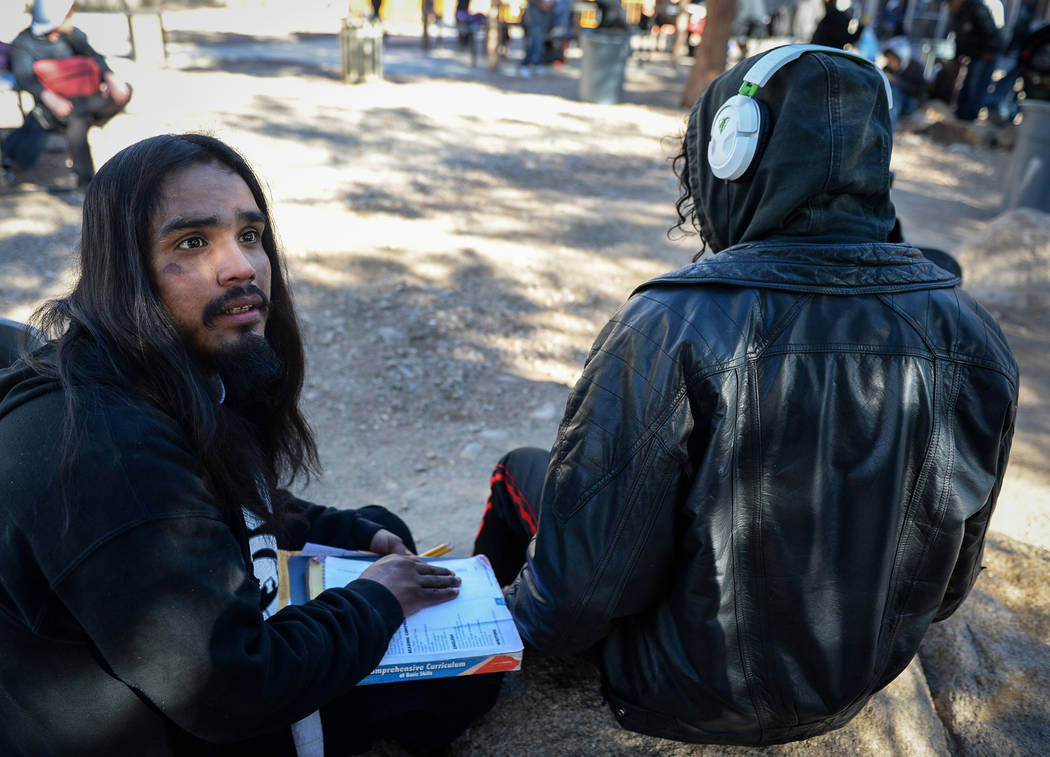

The courtyard has succeeded in providing a relatively safe harbor for the homeless. About 200 people typically sleep there each night on mats in the open-air courtyard.

When it rains, residents usually sit on tables set up under an overhang. When it’s cold, radiant heaters warm the covered area. In the summer months, cooling stations offer respite from the heat.

On Tuesday morning, a mobile shower van was parked outside the courtyard. Though it was windy and only about 50 degrees, residents made their way there, some clad only in T-shirts, shorts and flip-flops.

Among those sitting at the tables was 60-year-old Douglas Warenback, wearing a sweatshirt, a beanie cap and a plaid scarf.

Warenback, who has been staying at the courtyard since being released from prison in April, said he has seen changes since CHIPs departed and the city took over.

For one thing, it was easier to get bus passes before, he said.

“One day, they (CHIPs) all disappeared, and then I saw the news article about the contract,” he said. “There are politics that go on, even in these charitable organizations.”

Whatever the politics of the situation, thousands of emails from city officials reviewed by the Review-Journal show that dissatisfaction with CHIPs surfaced quickly after it was hired to operate the courtyard.

Beginning in August, officials raised safety and health concerns and noted that operational disagreements had prompted some other homeless service providers to withdraw rather than work with CHIPs.

One of those was Silver State Health Services, a nonprofit recommended by the city as a provider of mandatory behavioral health assessments, therapy, social work and counseling at the courtyard. It, too, had sought the contract that went to CHIPs.

Silver State pulled out in August after several disagreements with CHIPs over the reporting of data, how clients signed up for medical services and a lack of office space for its staff, according to emails between city staff and CHIPs.

‘Destined for failure’

In a letter to the city, CHIPs asserted it had arrangements with other providers to replace the services Silver State that had provided.

But Ryan Linden, Silver State’s executive officer, said CHIPs staff thought they could provide the services themselves, leading to the departure.

“It seemed potentially destined for failure from the start. I’m pretty satisfied that it (the contract) was pulled from CHIPs, and the city seems to be doing a much better job with probably less money,” he said, adding that Silver State has been back operating at the courtyard three days a week for the last three weeks.

Other complaints described CHIPs employees at the site as lackadaisical and frequently absent.

“Coordinator does not live up to the job description to service the client. Client complaints go unnoticed,” read one email, apparently from a CHIPs employee.

Another said there were so few workers at the courtyard that residents often could not retrieve their belongings from behind locked gates.

In one email, employees of the Allied Universal security firm said CHIPs staff did not properly secure a shade canopy at the site, despite several warnings from the city. The employees reported that strong winds ultimately tore the canopy loose, striking a resident and knocking her unconscious.

La Wanna Calhoun, a housing counselor from Madea House Adult care home, regularly went to the courtyard over the summer.

In July, she noticed a man inside the office wearing a CHIPs uniform and sleeping without shoes. He had been working for over a month and had yet to receive a paycheck, she said.

Another time, a client waited more than an hour for an employee to find her wallet. In a third instance, an employee struggled to get in touch with supervisors to place a family in emergency housing.

“With CHIPs, it was inconsistency, it was nonprofessional, it was a lot of different things,” Calhoun said. “It didn’t appear to me that they were providing the services that they were capable of providing, and that they had the funding to provide.”

“They told me they didn’t need help,” she added. “And it takes a village to help maintain and monitor and assist the homeless population.”

On Oct. 11 — four months after signing its contract with the city — CHIPs received a letter inviting it to “terminate for convenience,” a legal term meaning no cause for the early end was required.

The letter described the courtyard as being littered with trash and discarded food when inspectors visited. It also said CHIPs employees had used commercial laundry detergent to clean sleeping mats, rather than sanitizing them properly each morning to prevent the spread of disease.

Anderson, the CHIPs executive, said the issues highlighted in the letter had already been addressed or were in the process of being addressed. CHIPs officials also deny that there were ever any payroll issues that resulted in employees being paid late.

Many of the problems, she said, were caused by the city’s insistence that virtually every action the courtyard workers wanted to take — including posting signs and erecting canopies — required permission.

“There was a lot of frustration among our staff because they thought they would be able to do something, and when they got there, their hands were tied with how much they could help,” she said. “We don’t hold the purse, so we can’t handle people the way we see fit or the way we wrote out in our plan.”

Some of the city’s complaints involved services that were not CHIPs’ responsibility under the contract, Anderson said. She said her staff took on those tasks as a courtesy to the city, though it left CHIPs overextended and understaffed.

Corridor collaboration

Exiting the contract was an unexpected cost, but Bluitt-Fisher said the city is operating the courtyard within the original budget allocated to CHIPs.

Other organizations dedicated to serving the homeless, including Caridad and Catholic Charities of Southern Nevada, say they recently lost city and grant funding and suspect that could be related to the cost of operating the courtyard, though Bluitt-Fisher said those funds are part of a separate budget and were awarded through a competitive application process.

The loss of Catholic Charities’ grant of about $250,000 to provide housing for homeless families left a particularly noticeable void in the courtyard, which has struggled to find shelters where parents and children can stay together. Sometimes families are allowed to sleep in the courtyard’s limited office space.

Thomas Roberts, president and CEO of Catholic Charities, said he is concerned organizations like his, which have long experience addressing homeless issues in the area, aren’t involved in the decision-making about the courtyard.

“I hoped the city would come to us as the anchor in the corridor,” he said. “(But) the city is kind of taking it to do it on their own.”

Bluitt-Fisher said the city is committed to collaborating. It’s just a matter of how.

“The courtyard isn’t the end all, be all, or the only thing that the city is doing,” she said. “We have a lot of programs that we are trying to implement to address homelessness, and we’re still a part of the regional effort.”

The city plans to continue operating the homeless courtyard for the time being, with staffing provided by the temp agency, but discussions are underway about hiring a new operator, Bluitt-Fisher said.

“Everything is on the table,” she said. “From bringing the whole thing in-house to continuing on with the temp agency to bringing on another operator.”

It’s unclear when that decision will be made.

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.