Afghan who fled fall of Kabul lands in Las Vegas for Thanksgiving

Editor’s note: Benny, which is a nickname, spoke to the Review-Journal on the condition that his identity and certain details of his background not be disclosed out of concern for the safety of his wife and parents who remain in Afghanistan.

Benny believed his destiny was to come to America. After learning English, he served as an interpreter for U.S. military forces in Afghanistan when he was just a teenager. After graduating from college, he worked for a U.S. government contractor.

“I love the United States. I always have,” said Benny, 26. “My time with U.S. soldiers helping interpret for them allowed me to see Americans closely.”

Benny received threats urging him to stop working with the Americans. When the threats intensified, and shots were fired into his car, he took a job with an Afghan airline, thinking it would be safer for him and his family.

That job placed him at Kabul’s international airport in August, as the capital fell to the Taliban. For six straight days he helped evacuate fellow Afghans fearing reprisal under the new regime. The day of a suicide bombing at the airport, American soldiers insisted that Benny and his co-workers board a U.S. military aircraft, that their lives were in danger.

Benny had long wanted to come to the U.S. but not without his new bride. “It was chaotic, and I felt I had little say in the situation,” he said.

He was flown to Fort Dix in New Jersey for processing. After two months there, followed by one harrowing night in Dallas, the parents of the U.S. Air Force pilot who flew Benny to safety would welcome him into their Las Vegas Valley home, where he will spend his first Thanksgiving.

Dangerous flights

Air Force Capt. Christopher Hoffman’s first deployment as the aircraft commander of a C-17 cargo aircraft was supposed to be a routine one of transporting weapons and vehicles into Iraq.

“Then we started hearing kind of rumblings, you know, things were not going the way we’d expected in Afghanistan,” said Hoffman, 27, a graduate of Rancho High School’s aviation magnet program in Las Vegas.

The mission changed to evacuating Afghans out of Kabul in what became the most dangerous flying of Hoffman’s career, at high altitudes in scorching temperatures, over steep terrain and under fire.

“Normally when you depart an airfield, especially one that’s in the mountains, you get very specific instructions on how to do it safely, in order to avoid terrain and other aircraft,” Hoffman said. “The instructions the controller gave us put us on a collision course with two other aircraft, into other mountains and then a thunderstorm after that, because they were literally watching the Taliban walk into the city or explosions and gunfire beneath us as we were taking off.”

Pilots and crew members flew flight after flight under these conditions, with little time for rest and without complaint. “I saw my peers rise to the occasion in a way that still astounds me,” he said.

Hoffman piloted flights with 450 Afghans onboard, most of whom had never flown. Language and cultural barriers only intensified the terror of the passengers, who included the wounded, pregnant women and children.

Before one flight, Hoffman searched for an English-speaker who could provide instructions and information to passengers to ease their distress. He found Benny.

Distraught over leaving behind his wife and parents, Benny felt he was in no condition to perform the task.

“Despite my bad feelings — I was crying minutes before I accepted that role — I tried to be helpful to my country, to my people, even to that flight and their flying crews because that was needed,” Benny recalled last week.

Speaking with Hoffman after the flight, Benny told him how, he too, had wanted to be a military pilot. “I know that there is no Afghan air force anymore, but I wish one day I could be a pilot in the U.S. Air Force as a U.S. citizen.”

Grateful for the assistance, Hoffman gave Benny his phone number. Benny would soon need it.

‘Tore my guts out’

Hoffman’s father, retired U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Scott Hoffman, had deployed to the Middle East after the 9/11 attacks.

He believed in the mission. He wanted to fight terrorists so his children wouldn’t have to.

It also was personal. LeRoy Homer, an Air Force Academy buddy who had introduced him to his wife, Ellen, was the co-pilot of hijacked United Airlines Flight 93, which crashed into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, killing all onboard.

Scott Hoffman spent three years in the Middle East, including piloting reconnaissance flights over Afghanistan. He also served at U.S. Central Command, the administrative headquarters for military operations in the region.

“As soon as Kabul fell, like many veterans, it just tore my guts out,” the retired military officer said of this year’s withdrawal of U.S. forces. “We felt like we wanted to do something.”

Ellen Hoffman said, “We didn’t know what it was gonna look like, but if the opportunity presented itself, I think we were both kind of ready to be able to do something.”

Hungry and alone

When Benny arrived at Fort Dix in New Jersey for processing, he had no money, no SIM card to make cellphone calls and infrequent access to Wi-Fi.

He contacted Christopher Hoffman, who put him in touch with his father. Communicating mostly through an app, Benny talked with Scott Hoffman about his hopes of landing a job in IT, perhaps in Texas or California.

The Hoffmans tried to get money to Benny but encountered obstacle after obstacle, including that the base didn’t accept mail.

When he first arrived at Fort Dix, Benny had stated a preference for resettling in Texas. He provided officials with the contact information for a brother of a friend from the military base. The brother lived in Dallas. Later, at the Hoffmans’ suggestion, Benny tried without success to change his destination to Las Vegas.

Instead, he was put on a flight to Dallas. His caseworker was unavailable, and his friend’s brother met the flight. The brother took Benny to the lodging found for him: a tiny windowless room with no furniture and an empty refrigerator.

“I lost my hope,” Benny said. “I just wanted to go back to Afghanistan.” Despite the danger, at least he would be with his family, he thought.

Hungry, friendless and moneyless, he contacted the Hoffmans.

“He’s driving around inner-city Dallas looking for his place, and he’s sending me scared-eyes emojis,” said Scott Hoffman, a recollection that makes both him and Benny laugh. “He said it was really rough and very scary.”

Now a pilot with Southwest Airlines, Scott Hoffman obtained a free flight from the airline for Benny. The crew took up a collection for him. The next day Benny flew to Las Vegas.

For the past month, Benny has lived with Scott and Ellen in their home in Henderson. They are helping him to adjust to a new life and pursuing ways to reunite him with his wife and parents.

“It’s not that it’s been easy,” Ellen Hoffman said. “But so many times, doing the right thing is simple. And it’s clear.”

At first, Benny spent much of his time alone in his room. Gradually Benny, and his playful personality, emerged.

“For the very first days, I was a little bit shy,” he said. Now, “When I wake up, basically, I come out of my room to say ‘hello, good morning’ to my family,” the Hoffmans. “And then they taught me how to prepare breakfast for myself, and we’re still working on that,” he said with a laugh.

Aid for evacuees

The Hoffmans connected Benny with the African Community Center, a Las Vegas agency tasked with assisting Afghan evacuees with resettling in Southern Nevada.

The center’s director, Milan Devetak, said that Benny is a “humanitarian parolee,” a designation that allowed him and other Afghan evacuees to enter the U.S. legally without the yearslong wait facing many refugees. He must now petition to stay in the country and for his wife to join him in the U.S.

Of the 100 Afghan evacuees the center has committed to resettling in Southern Nevada, 77 already have arrived, according to Devetak. Like similar agencies across the country, the small nonprofit has been overwhelmed by the rapid influx of the Afghans and meeting their immediate needs. Housing poses a particularly daunting challenge.

“Housing is almost impossible for us to find,” Devetak said.

In Southern Nevada, there already are wait lists for low-cost housing. Long-term rental budget hotels are nearly full. Then, too, there is reluctance to rent to someone without a job, credit history or references.

But “almost impossible” is not the same as impossible. Through a grant to Airbnb, most of the evacuees are staying their first month in vacation rentals, after which other arrangements will need to be found, Devetak said.

With lodging not an immediate concern, Benny is focused on other issues. The center is helping him to obtain authorization to work legally in the country so he can get a job. For how, Benny is volunteering as a translator at the center.

The center is partnering with the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada to assist Benny pro-bono with his petition to remain in the U.S. and his efforts to reunite with his wife and parents.

In hiding in Kabul

Benny’s parents have left their home and are in hiding with his wife in Kabul. They have little money or food. When they were questioned by the Taliban, Benny’s wife lied about his whereabouts; most of the 70,000 Afghans evacuated to the U.S. had assisted the U.S. government in some way and would be viewed by the new regime as traitors.

“Every second, every minute, they have to worry what’s going to happen next,” Benny said.

Ebru Cetin, a staff attorney with the Family Justice Project at the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada, said she could not speak about a specific case but agreed to address in general terms the legal hurdles faced by Afghan evacuees.

Congress has prioritized the petitions of the Afghan evacuees to stay in the country, she said. It has asked that their interviews for asylum occur within 45 days of application and that decisions be rendered within 150 days. However, a case backlog could affect the timeline.

Special immigrant visas also are available to Afghans who have worked as interpreters for the U.S. government, though it’s unclear whether this route would result in a speedier resolution, she said.

Once an evacuee is granted asylum, he or she can petition to be reunited with a spouse or children. There are separate, less straight-forward processes by which parents and other relatives can enter the country.

Afghanistan’s upheaval and the absence of a U.S. Embassy complicate an exit from the country. Ensuring safe passage for people who are in hiding poses further challenges.

The Hoffmans have asked their congresswoman, Rep. Susie Lee, and U.S. Sens. Catherine Cortez Masto and Jacky Rosen to intervene on behalf of Benny’s family. Cortez Masto’s office is coordinating the effort.

A representative said the senator and her staff have been working with the State Department and the Biden administration to help Nevadans and their relatives who have contacted them for help.

“We’re doing the legwork,” Ellen Hoffman said, speaking directly to the lawmakers. “We will do the paperwork, we will hand deliver this stuff to you if you want. Now you need to do your part. You need to push through and get in touch and do what we elected you to do.”

Thankful for much

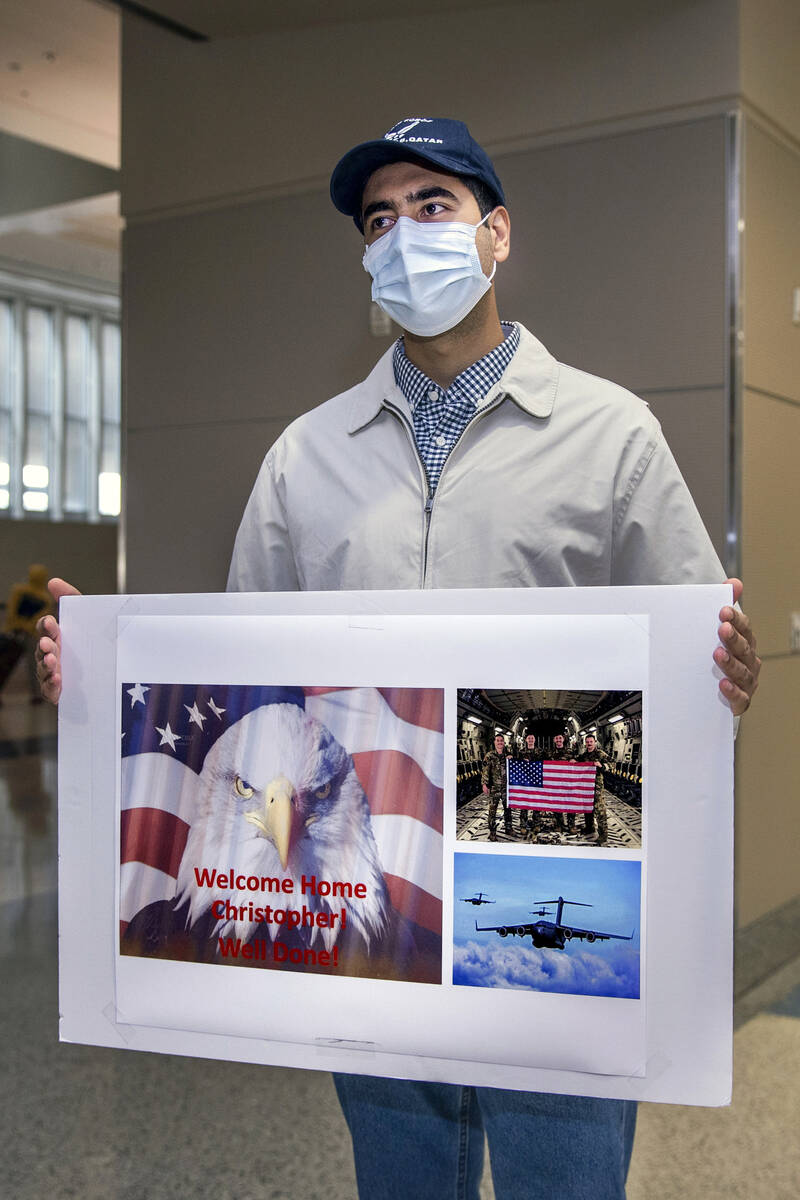

Benny is celebrating his first Thanksgiving with the Hoffmans, including Christopher, who flew in on Friday with his wife, Kristin, and the couple’s 6-month old daughter, Caroline. Joining them is Christopher’s sister, Hailey, with Ellen’s parents and nieces.

Benny said he is grateful for the Hoffmans.

“The best thing that I have is a family that are taking care of my food, my money, my outfits, everything,” he said. “And they are taking care of me — not only the financial part, they are taking care of my feelings. They’re trying to make me feel comfortable and they are talking to me about my family. … Their support is giving me strength and hope.”

Scott Hoffman said that Benny has given back to his family in unexpected ways.

“Many vets, like me, were devastated when Kabul fell. So much blood, sweat and tears seeming to be erased in an instant,” the retired officer said. “Having Benny with us made me realize it was not for nothing.”

“We kept the homeland safe,” he continued. “One Afghan generation grew up, had a chance at an education and a chance to dream big. Some of those fine people are now in the U.S. and will be great citizens.”

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.

How you can help

The African Community Center is part of the Ethiopian Community Development Council, one of nine organizations nationally contracted by the U.S. government to aid refugees with resettlement. Catholic Charities, which also operates in Southern Nevada, is another.

To volunteer or donate to the African Community Center, visit acclv.org or call 702-836-3324.