Watch your head! A trip through Nevada’s breathtaking Lehman Caves

GREAT BASIN NATIONAL PARK — The temperature drops a degree in unison with each footstep — or so it seems — as you walk down, down, down into the darkness.

You feel the chill before you see where it emanates from — should have worn a jacket — while descending through a long concrete tunnel towards a metal door that opens into the basement of the earth.

Cross the threshold, and it takes a second for pupils to begin processing the modestly-lit surroundings, though olfactory senses require no such adjustment period: a thick scent of moisture-saturated stone, the perfume of the underground, engulfs you all on all sides the way the smell of popcorn seemingly permeates every inch of a movie theater.

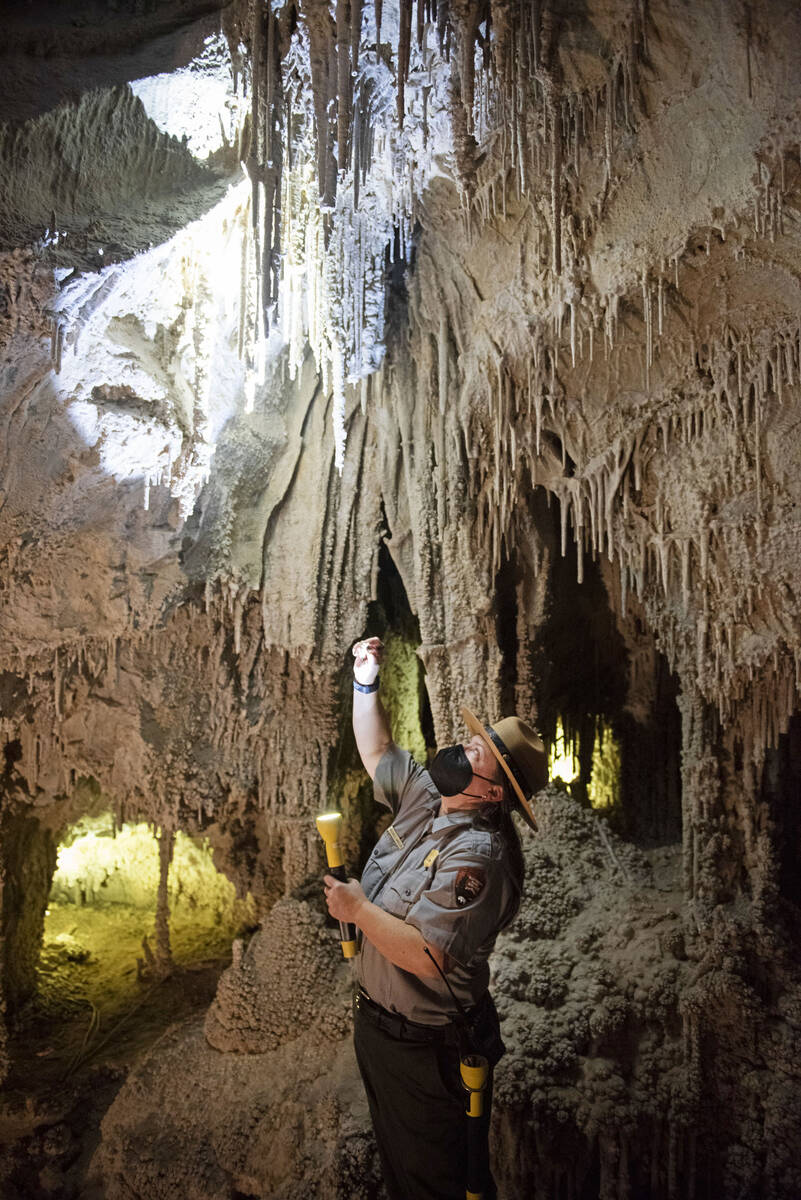

Nichole Andler flicks off the lights.

“This is what the cave naturally looks like,” our tour guide says.

Thing is, it looks like nothing at all right about now — like, nothing — the purest distillation of the color black come to life, like your eyeballs have momentarily been plucked from your skull and replaced with little lumps of coal.

Think of it is as entering a mammoth, cavernous sensory deprivation tank carved from limestone and marble: calming, dislocating and a little unsettling all at once, this feeling of being cocooned in complete and total silence.

It’s a cool moment — literally, it’s around 50 degrees in here — a sort of visual palate cleanser preparing you for what’s to come, a breath-stealing journey through a 2.5-mile long labyrinth of some of nature’s wildest architecture, millions of years in the making.

And then the lights come back on, and so many shapes emerge from the shadows all at once, organic and alien-looking simultaneously.

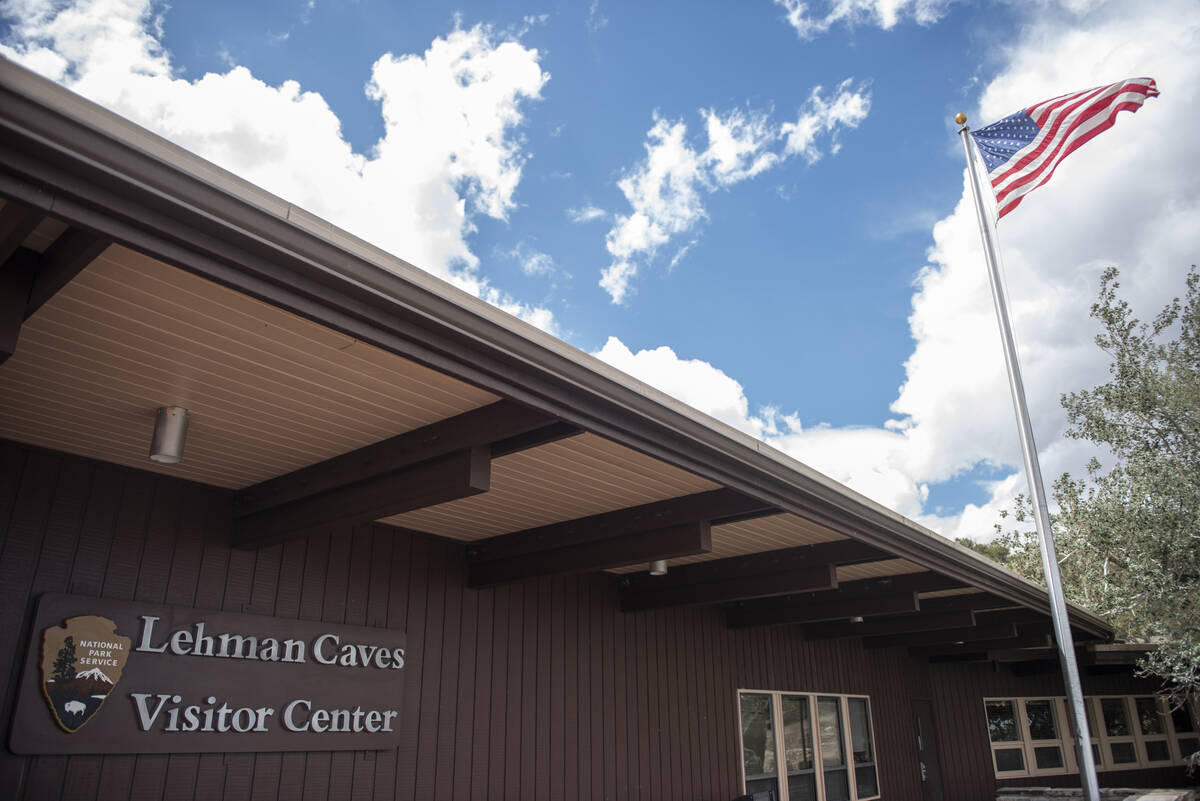

We’re about to embark on a trip through Lehman Caves, one of Nevada’s most enthralling natural attractions, nestled in the Great Basin National Park near Baker, Nevada, about a four-hour car ride north of Las Vegas.

One hundred years ago this weekend, ceremonies were held here commemorating President Warren Harding declaring Lehman Caves a national monument earlier in 1922. On Saturday, the occasion will be celebrated with a day of events at the site, including lantern tours of the caverns just like visitors would have taken a century ago.

It’s sunny outside on a recent Monday morning when we enter the caves for a tour of our own.

It’ll be nearly two hours before we see daylight again.

Millions of years in the making

Did this really all begin with a thieving pack rat?

As she stands before the cave entrance, sporting a park ranger’s hat and an air of indefatigable enthusiasm, Andler shares one of her favorite tales about how Lehman Caves first caught the eye of a local prospector and rancher around 1885.

The story detailing how these dark caves initially came to public light was never officially chronicled back in the day, so it’s become a thing of regional folklore.

According to this particular yarn, cave namesake Absalom Lehman was outside his cabin one day when he noticed the aforementioned rodent scurrying off with one of his possessions — something shiny, gleaming beneath the sun.

Lehman gave pursuit and eventually happened upon the caves after his horse gave out beneath him.

“That might be a bit of a tall tale,” Andler grins.

Truth is, no one knows exactly how Lehman came across the caves, though he likely found them while herding sheep or looking for stray cattle, according to Andler. (To say he “discovered” the caves would be inaccurate, as Native Americans utilized them for burial grounds long before Lehman came around).

Lehman then helped turn the caves into a tourist attraction, forging a path through the winding maze of rock.

In January 1922, the site became a national monument. Eleven years later, management was transferred to the National Park Service, and then in 1986, the caves were incorporated into Great Basin National Park upon its creation.

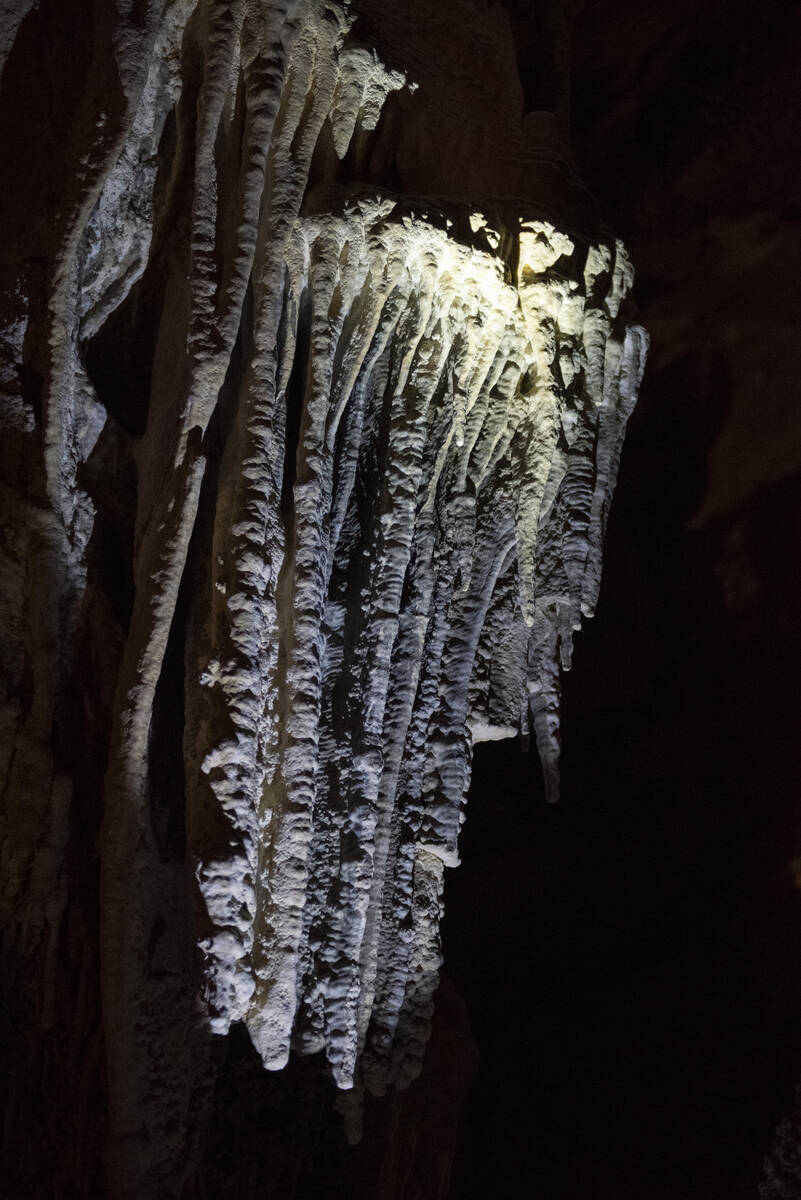

The caves are at least 2.8 million years old, the age that one of its rock formations has been dated back to, formed by a combination of warm water coming up from below to carve the rock into the assorted rooms we travel through, as well as water from the surface picking up carbon dioxide from decaying plant and animal material — forming carbonic acid — and then dissolving the limestone and marble from above.

Upon dripping down, the water releases some of that carbon dioxide and deposits the calcite crystals into stalactites, which descend from the ceiling of the cave, and stalagmites, which extend up from the floor.

During our visit, we spot several places where water continues to drip.

Nearly three million years in and counting, the Lehman Caves keep on growing right before our eyes.

Introducing the cave turnip

“Watch your head!”

Andler issues the command with the frequency of a Walmart greeter instructing customers to have a nice day.

Walking through here, the space becomes tight at times, requiring you to bend your body Gumby-style to navigate the occasional narrow passageway and duck beneath numerous low-hanging rock formations as if dodging blows from Mother Nature herself.

This is part of the appeal.

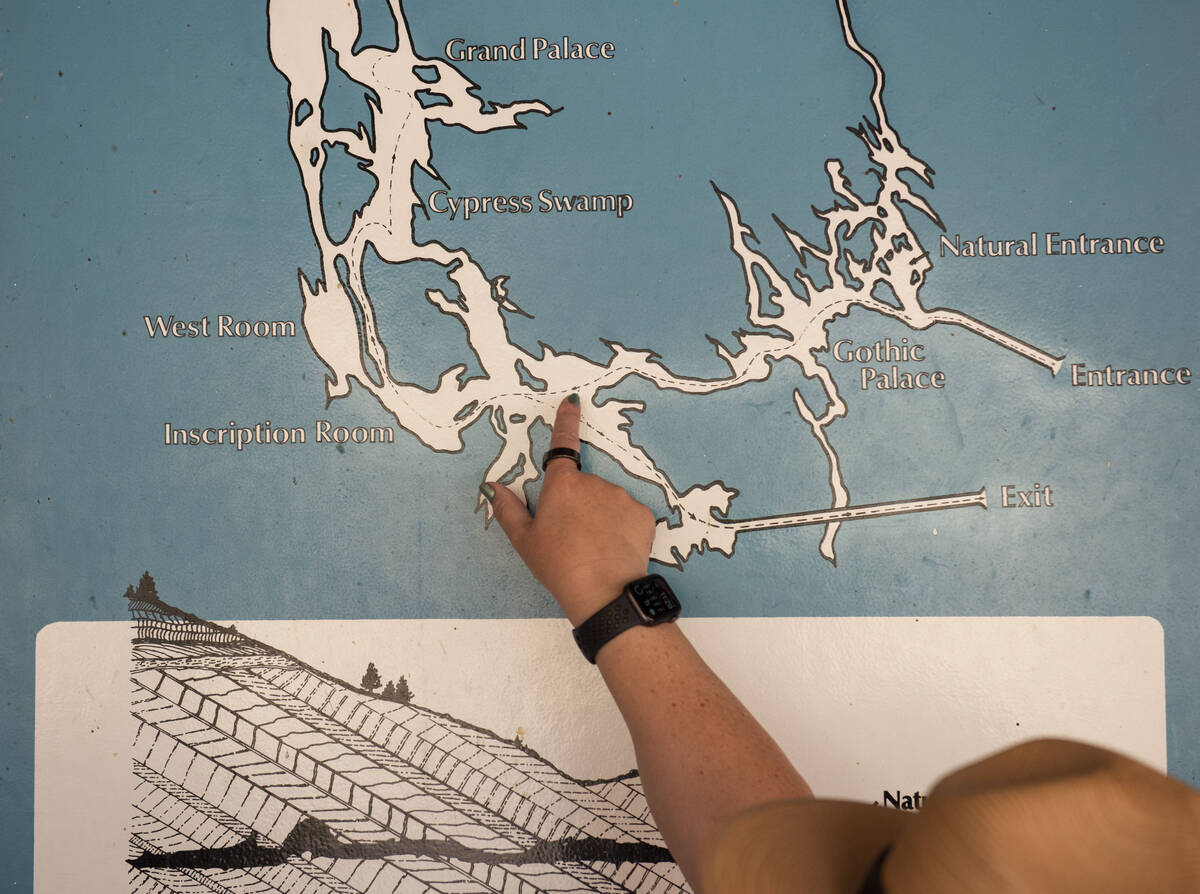

While there are much larger caves to visit in the Southwest — including the 100-plus caves found at New Mexico’s Carlsbad Caverns State Park, some of which extend over 30 miles — exploring Lehman Caves is a much more intimate, up-close-and-personal experience.

Think of it like seeing Metallica — if Metallica was a gnarly assortment of rocks — in a small club as opposed to a 20,000-seat arena.

About midway through our tour, we encounter another distinguishing trait of Lehman Caves: the Parachute Shield, a towering geological specimen that looks kind of like a frozen waterfall or an up-ended bowl of spaghetti, stalactites in place of noodles.

“The Parachute Shield is really the shield that became the icon of Lehman Caves,” Andler explains. “It was a famous one that got the word out, ‘Lehman Caves has shields.’”

In addition to its cozy dimensions, one of the main attractions here is the abundance of “cave shields,” large, round rock formations made of two adjoined plates.

They’re a rarity in most caves.

There are over 500 of them here.

“It’s the shields that made us special,” Andler notes.

She guides us to a pair of the structures in question, which she’s dubbed the Captain America Shield and the Jabba the Hut Shield, highlighting a key component of the Lehman Caves experience: identifying rock formations that look like famous and/or real-life things, a baby alligator here, a big-eyed frog there.

It’s kind of like a subterranean version of pointing out animal shapes in cloud formations, locating the bunny rabbit in the sky.

Speaking of which, Andler halts the tour at one point and gestures to a spot high above her head, where a group of rotund stalactites hangs.

She calls them Cave Turnips, due to their similarity to the vegetable.

While most stalactites are longer than they are wide, there does exist a variety of them called bulbous stalactites that form underwater.

Seeing as how she and her colleagues don’t think that these caves were ever fully submerged all the way to the ceiling, this could be a new discovery unique to these parts.

“We are calling these Turnipites,” she says. “Our very own thing from Lehman Caves.”

Rock on

Our tour culminates where B-movie astronauts once tread in a make-believe realm teeming with monstrous maggots and low-budget extraterrestrials.

We’ve entered The Lodge Room, one of the more spacious stops on our trek.

Back in the mid-’60s, scenes from cheese-tacular “Wizard of Oz” sci-fi spoof “Wizard of Mars” were shot here, complete with the aforementioned creatures and all their cringey costumes.

Four decades prior, when Prohibition was still in effect, this space was sometimes used as a speakeasy.

“They literally had a band down here,” Andler says, “so you could dance.”

There’s also been a number of marriages here — you can still get hitched on the premises — the last one taking place in 2018.

The Lodge Room is the final stop on our journey.

We’ve passed through the Music Room, where tour guides once made its titular “music” by pounding the walls with hammers until they stopped doing so because of the obvious damage being done to said walls; the Inscription Room, where visitors were allowed to scrawl their initials on the ceiling decades ago (Don’t break out the Sharpie today, you’ll be cited for graffiti); and myriad other spots rich in history and mineral deposits alike.

Along the way, Andler notices a patch of especially dark brown rock, indicating that it’s heavily comprised of iron.

She’s been leading tours for eight years now, and this is the first she’s seen of it.

“Almost every time when I go in the cave, I notice something different — still,” she says as we hike towards the exit, underscoring the nuance and depth of the landscape she’s traversing, a geological puzzle all but impossible to complete.

To everyone’s surprise, it’s raining when we emerge from the caves around an hour-and-a-half after entering.

No one had any clue a stormfront had moved in.

How could we?

We were navigating another world entirely.

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram