LAKE HAVASU CITY, Arizona — It’s story is improbable as its presence here, 33,000 tons of granite, 5,295 miles from home.

Built beneath Britain’s gray skies, currently baking beneath the Southwestern sun, there simmers the world’s largest purchased antique.

How did the London Bridge get here, in Lake Havasu City, Arizona, of all places?

Stone-by-hand-numbered-stone, 10,276 in all — that’s how.

Purchased in 1968, it was completed three years later.

Back then, Lake Havasu City was a city in name only, with a population of around 1,000.

And then a serial entrepreneur partnered with the man who designed Disneyland to create perhaps the region’s most unlikely tourist attraction.

Fifty years later, Lake Havasu City now draws nearly one million visitors annually.

“This bridge is basically the corner stone of this community,” says Terence Concannon, president/CEO of the Go Lake Havasu tourism bureau, “created what it is today.”

And it all began with the most curious of imports.

“I talked with one of the builders of the bridge — he’s not with us any more — he said, ‘The London Bridge gave us our identity,’” recalls Jan Kassies, director of visitors services for Go Lake Havasu. “I think that is so true, because without the bridge, we would have been a little town somewhere in Arizona, on a lake. There are many more of those. But the bridge gave us something extra.”

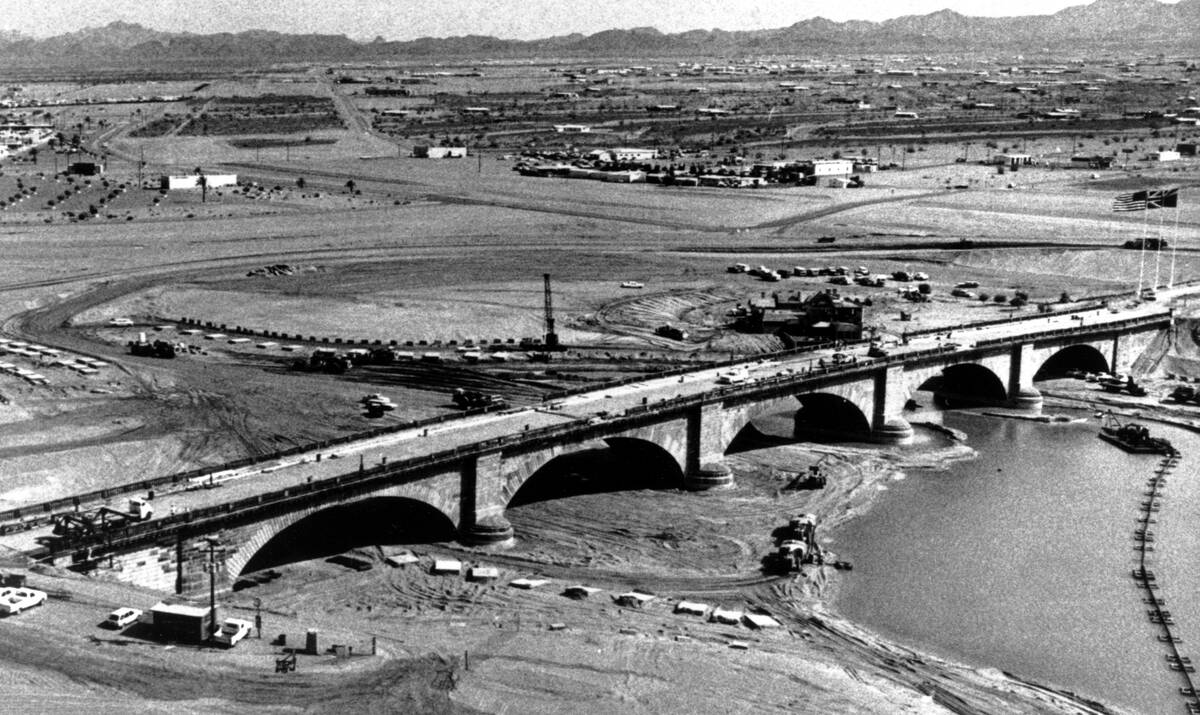

Thousands of people walk across the London Bridge for the first time after its opening in Lake Havasu City, Ariz., on Oct. 10, 1971. (AP Photo)

Thousands of people walk across the London Bridge for the first time after its opening in Lake Havasu City, Ariz., on Oct. 10, 1971. (AP Photo)  This is an April, 1968 photo of the London Bridge as it is being dismantled over the Thames river in London, England. (AP Photo)

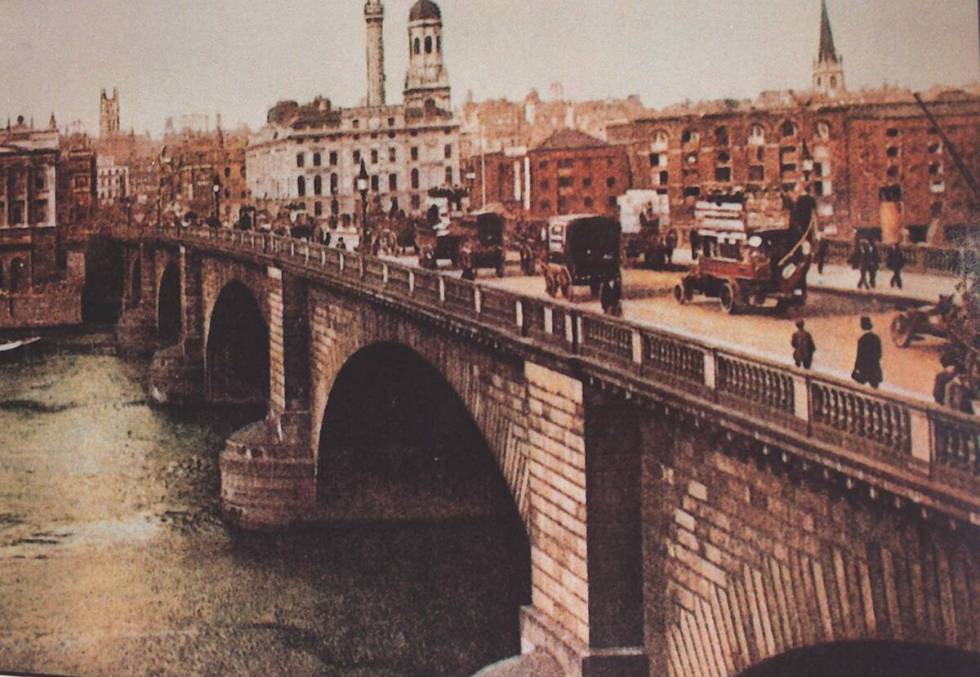

This is an April, 1968 photo of the London Bridge as it is being dismantled over the Thames river in London, England. (AP Photo)

A city rises in the desert — sort of

There’s a chainsaw in the Lake Havasu City Visitor Center.

It’s a prime reason the city exists.

Enter Robert P. McCulloch, a Missouri-born, Wisconsin-raised Harvard grad who sold his first business, McCulloch Engineering Company, for $1 million before he was thirty.

The Midas-touch industrialist would move to Los Angeles, and by the late ’50s, was looking for a place to both test outboard motors and relocate his chainsaw manufacturing plant.

He discovered the Lake Havasu area, once a military site, purchasing a 26-square-mile parcel of land there in 1963.

Thing was, McCulloch wanted to build a town, a watery oasis in the desert, a destination spot amid the cacti, heaven with jet skis.

His recruited his friend, business associate and Disneyland designer C.V. Wood Jr. to create the city’s unique layout.

“No streets are straight for more than a couple blocks,” Concannon says. “All of the streets curve in sort of semi-circle fashion around the lake shore. The idea was that any house, any location, any address in the city would have a view of the lake. And it is pretty much true.”

McCulloch flew potential land buyers into the town, pitched the place hard, but business wasn’t booming the way he wanted it to — the way he was used to.

“I think he brought about 35,000 people over here, but not everybody bought a piece of land,” Kassies says. “It went slow, slow, slow.”

And so it was time to think fast.

Pedestrians walk across London Bridge on Saturday, Oct. 2, 2021, in Lake Havasu, Ariz. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Pedestrians walk across London Bridge on Saturday, Oct. 2, 2021, in Lake Havasu, Ariz. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye  A boat travels under London Bridge on Saturday, Oct. 2, 2021, in Lake Havasu, Ariz. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

A boat travels under London Bridge on Saturday, Oct. 2, 2021, in Lake Havasu, Ariz. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye ‘Who wants a bridge?’

The nursery rhyme was prescient; the song was coming true.

The London Bridge really was falling down. (The second one, anyway; the original structure was erected in 1209 and lasted over 600 years).

Completed in 1831, the thing was sinking into the River Thames by the 1960s.

“It wasn’t used to vehicular traffic,” Concannon explains.

A London councilman suggested selling the bridge.

Cue the scoffs from his fellow city officials.

“They said, ‘Well, that’s kind of weird. How can we sell a bridge?” Kassies says. “Who wants a bridge?”

Robert P. McCulloch raised his hand.

What better/more absurd way to create headlines, attract eyeballs to the burgeoning community he was attempting to build?

Attendees enjoy their meal during Royal Jubilee Celebration for the 50th anniversary of the London Bridge on Saturday, Oct. 2, 2021, in Lake Havasu, Ariz. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Attendees enjoy their meal during Royal Jubilee Celebration for the 50th anniversary of the London Bridge on Saturday, Oct. 2, 2021, in Lake Havasu, Ariz. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye  Leslie Rosario, left, Rise Mann, dressed as a lady-in-waiting, in medieval times, and Sandra Willis, dressed as Lady Casandra, twice removed cousin to the Queen, Oct. 2, 2021, in Lake Havasu, Ariz. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Leslie Rosario, left, Rise Mann, dressed as a lady-in-waiting, in medieval times, and Sandra Willis, dressed as Lady Casandra, twice removed cousin to the Queen, Oct. 2, 2021, in Lake Havasu, Ariz. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

“He told his friend, ‘I’m going to buy the bridge,” Kassies explains, “because if we have the bridge, (people) will pay attention to our town, to our development.’ I had heard that his friend said, ‘My god, you are the weirdest guy I ever met.’”

Undaunted, McCulloch paid $2.6 million for the bridge: double the $1.2 million cost for tearing the structure down, equating to a 100% profit for the city of London, plus an extra $1,000 for every year the bridge would have been in existence by the time of its reconstruction, which totaled six decades and $60,000.

The bridge was cut into granite blocks to be placed around a structure built in Lake Havasu City.

The blocks were transported by sea, through the Panama Canal to the port of Long Beach, California and then trucked to Arizona.

Each one was numbered, to be put back together like a giant jigsaw puzzle.

The bridge was built over land at the tip of a peninsula on Lake Havasu, a one-mile channel dredged beneath it, over two million yards of cubic earth excavated to allow the lake to flow under it.

It took a 40-man crew a year-and-a-half to complete the project at a total cost of $5.1 million.

On October 10, 1971, McCulloch presided over an extravagant dedication ceremony that lured an estimated 25,000 spectators to the bridge.

This weekend, Lake Havasu City will commemorate the 50th anniversary of the London Bridge with another celebration.

It’s now a town of 57,000.

Bridging the past

The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Teddy Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, intrepid Review-Journal reporters — they all walked this bridge.

It’s a Wednesday afternoon in September, and history can be seen here, felt here.

Touch the lampposts. They’re made from the melted-down cannons captured by the British from Napoleon’s army after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Trace the inscriptions made by two American soldiers from the First Infantry Division who carved their names into the bridge in 1942: Sgt. Fitzwater; PFC Smith.

There are bullet holes from the battle of London pockmarking the bridge’s facade, one of the only places in the continental U.S. where the scars of World War II are visible on American soil.

The structure in question doesn’t just bridge Lake Havasu, it bridges countries and cultures, the past and the present.

“It’s taking a piece of history from another continent, another heritage and transplanting it over here,” Concannon says. “It’s Lake Havasu’s bridge, but there’s still that history and mystery of Old London in there.”

Today, the London Bridge stands as monument to left-field ingenuity, to far-out entrepreneurship, a massive piece of 19th-century British architecture surrounded by palm trees.

It’s very existence feels implausible.

Kind of like Lake Havasu City itself.

“It has become the very focal point of not just the city itself, but of how people view the city,” Concannon says. “People view Lake Havasu City as a city born of innovation and of quirky ideas. That’s basically what we still are.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram