New book on pet cemeteries examines our deep bond with our pets

It’s the old chew toys that really get you.

Lying on its side, encircled in stone, there’s Peaches’ green rubber porcupine, collecting desert dust for decades.

Beneath a cast-iron cactus, oxidized by the elements, sits a phalanx of Friskey’s stuffed cats.

A few steps away, a dog’s teddy bear — head gnawed off, wisps of cotton blowing in the breeze — memorializes days of play gone by.

Here lies the final resting spot of “Beloved bunny Daisy,” Jack the kitty — “you were a good cat,” his feline-shaped wooden grave marker notes — and a slobbery pooch named General, whose leash hangs over a white cross fashioned in his honor. “Long live the drool,” bears its inscription, written in black ink, punctuated by a hand-drawn heart.

All around us, on this ragged patch of land just off the highway a few miles south of Boulder City, so many family pets have been buried in the sand that crunches beneath our feet.

The spot is hard to find, marked only by a small, oft-ignored sign prohibiting pet burials on federal grounds — the graves here are as recent as this year.

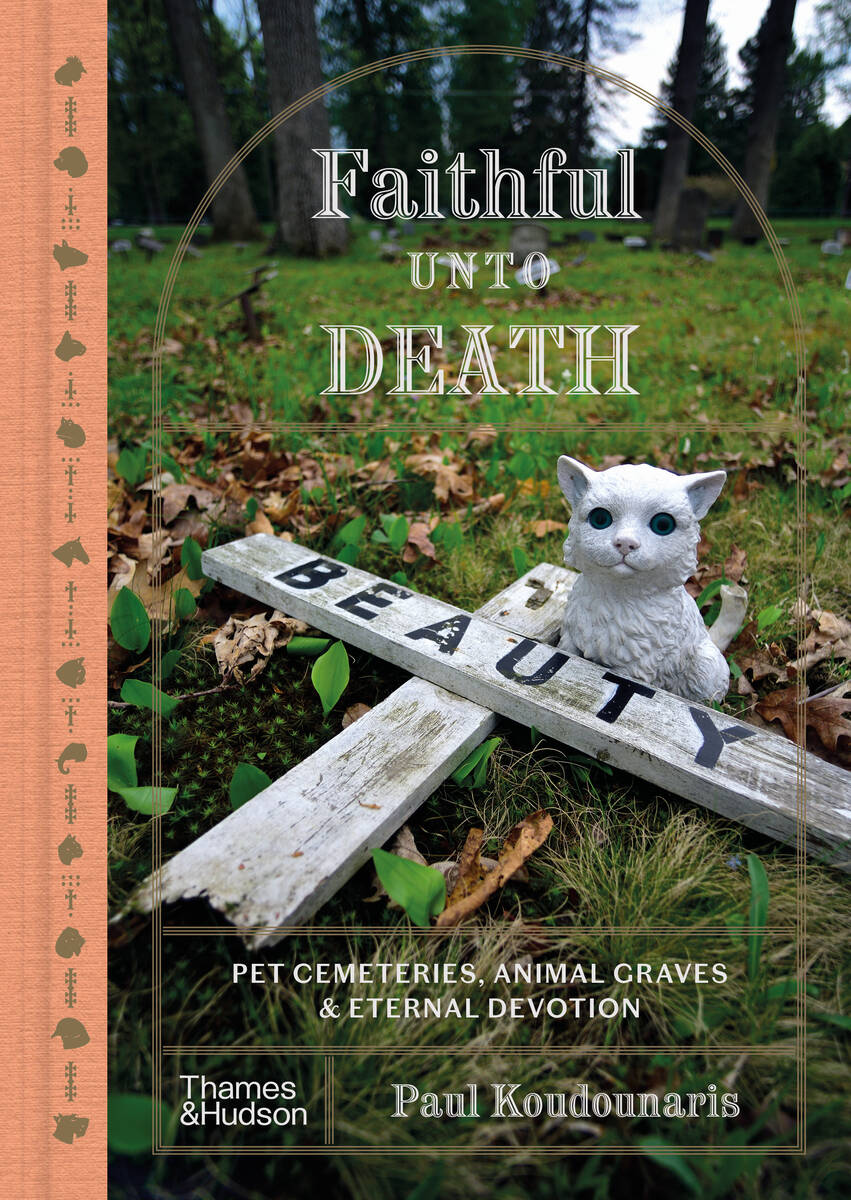

“This place is weirdly legendary,” notes our tour guide, Las Vegas-based author Paul Koudounaris, whose just-released book “Faithful Unto Death” chronicles the history of pet cemeteries, like this one.

As documented in the book, the Boulder City animal graveyard was founded in the 1950s by a worker for the Bureau of Reclamation, who also doubled as the town’s unofficial veterinarian. He originally wanted to open a pet cemetery as part of the town’s municipal burial grounds, a big no-no at the time.

When the city declined, he began burying pets in the desert alongside a stretch of the I-95 instead. In the years since, it’s gained infamy for supposedly being haunted and speculation that the Mafia once disposed of bodies there, as Koudounaris notes.

Walking through the expansive burial grounds, though, those rumors give way to something more tangible: a palpable sense of the deep emotions that the loss of a pet can inspire, manifested here in one homemade memorial after the next, some of them elaborately designed, like a large, intricately carved wooden butterfly dedicated to deceased cat Calico (“You will always be in our hearts. You will always be our Kittyco,” it reads in part). Others depict little more than an animal’s name and lifespan carved into stone — “Kaiser 2016 to 2024” — austere in presentation, rich in sentiment.

With Koudounaris leading the way, his feathered, magenta hat countering the desert drab around us, we come across a burial site marked by a statue of St. Francis of Assisi, the Italian friar known for his patronage of animals.

“Catholic dog,” he quips. “Almost every pet cemetery you go to, there’s a St. Francis of Assisi.”

Koudounaris would know: for the past 11 years, he’s crisscrossed the U.S. and England and traveled as far as Bali, Bangkok and Bolivia to visit pet cemeteries for his book.

While “Faithful Unto Death” recounts in meticulously researched detail the history of pet burial grounds and tells the stories of some of the more famous animals intered there — among them: star 1930s movie dog Dumpsie, who died by poisoned meatball, and Blinky the Friendly Hen, a frozen, headless chicken — at its core, the book’s really an emotive, in-depth examination of the bond we form with our pets, a bond that can run so deep, they often become a part of the family — and maybe even more of a welcome one than certain in-laws.

And so what happens when a pet dies?

A part of us does as well — or so it can feel like.

“People who have been through that would understand: that’s a family member, too,” Koudounaris says. “And that’s what the book is about: That connection.”

‘It always breaks your heart’

Every day, he got on the phone and fought back tears while others shared theirs.

In preparation for writing “Faithful Unto Death,” Paul Koudounaris spent a full year as a volunteer grief counselor for people whose pets were dying or had recently passed.

“As a writer, you have to get past your own perspective to really understand a subject,” he explains. “Every single day, no matter what I was doing, I always made time for that. And there would not be a single day that entire year where something that someone said did not break me.

“That’s why I only did it for a year, because I’ve experienced that,” he continues, “and then listening to other people experience it — it’s different for every person, but it always breaks your heart.”

In a way, the publishing of “Faithful” is a sadly timely one for Koudounaris: one of his cats, Baba, who’s featured in his 2020 book “A Cat’s Tale: A Journey through Feline History” where she’s dressed in a series of historical costumes hand-sewn by Koudounaris himself, is nearing the end of her life.

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, she strolls into the living room of Koudounaris’ condo in the central part of town, where one wall is dominated by a large tapestry depicting a cemetery setting and another comes arrayed with a collection of mounted goat heads (His grandfather raised them).

Baba — one of two cats who roam around the place, the other being a sociable male named Walter — seems in good spirits still, climbing on visitors for pets.

“She doesn’t quite know what’s going on, but she still likes life,” explains Koudounaris, who tends to speak in soft tones, which takes a bit of the edge off the prevailing subject matter at hand: death — and its many reverberations.

It’s a subject matter that Koudounaris seems almost destined to explore: Even as a kid, he was obsessed with what was going to be written on his gravestone one day.

“I’d come to the dinner table, and I’d tell my mom, ‘Hey, if I die, will you write on my grave that I liked animals? ’ Or, ‘Will you write on my grave that I wanted to be a scientist or something?’” he recalls, his tattoos, piercings and colorful headgear lending him the air of a sociable swashbuckler. “And my mother would be like, ‘Get the psychiatrist. This is death. This is bad.’ But it was out of curiosity and fascination.”

This fascination would only grow over the years.

After completing his Ph.D. in 16th and 17th-century European art at UCLA, where Koudounaris describes himself as the Fox Mulder of the art history department — “Everyone else was going to go out and do something new on some new iconography, and I was like, ‘I’m going to work on woodcuts of werewolves.’ I was the one who was always doing the weird stuff” — Koudounaris was bumming around abroad when he began visiting old-world burial sites.

This begat his first book, 2011’s “The Empire of Death: A Cultural History of Ossuaries and Charnel Houses,” which he’d follow up with two more tomes on death: “Heavenly Bodies: Cult Treasures and Spectacular Saints from the Catacombs” and “Memento Mori: The Dead Among Us,” the latter’s title referencing the Latin phrase for “reminder of death.”

The idea for his latest book came over a decade ago, when a friend encouraged Koudounaris, who was living in Los Angeles at the time, to check out a pet cemetery in Carson, California.

“I went down there one day, and I just walked around, reading the graves and taking a few pictures,” he recalls. “All these other places filled with the human dead, none of them had ever broken me in that way, because there was an earnestness to those little graves and the inscriptions and seeing little pictures on the ground.

“I thought I was bullet-proof,” he continues, “because I had done three books in a row, traveled to 70 countries, looking at dead people. And that’s what stuck in my heart in a way nothing else had. I was like, ‘Yeah, there’s something here.’”

A brief history of burying man’s best friend

It all began with Cherry’s end.

A Maltese who lived in 19th century London, the little dog’s fondness for fetching the daily mail was rivaled only by walks in Hyde Park, as Koudounaris recounts in “Faithful.”

He did so with such frequency that his owners became friendly with the park’s gatekeeper, who lived in a cottage on the grounds.

Upon Cherry’s passing in 1881, his family asked the gatekeeper if the dog could be buried in his garden.

He agreed, word spread, and other grieving pet owners soon made the same request.

And with that, the modern-day pet cemetery was born.

This was no small thing: back in those times, burying pets was often viewed with scorn, dismissed as a display of over-sentimentality for a mere animal.

And attempting to lay a dog or cat to rest in a human cemetery was seen as an act of borderline sacrilege.

As Koudounaris details in his book, when a widow buried her pet terrier in a municipal cemetery in New York in 1888, a local newspaper called it one of the “most disgusting incidents of the present year.”

The dog was exhumed.

“One of the things I get into in the book is this difficulty that people had in the 19th century of making people understand that when their animal died, this was a family member and it deserved the same love and respect upon his death,” Koudounaris explains.

In 1896, America’s first pet cemetery opened in Hartsdale, New York as chronicled in “Faithful,” a 256-page, lavishly designed, picture-heavy cross between a history book and an art book released by the prestigious publishing house Thames & Hudson. Koudounaris took all of the photos himself, taking a full month shooting the iconic gravestone for Dewey the cat in Massachusetts’ Pine Ridge Cemetery just to get the sunlight right).

As pet cemeteries spread across the country, the inscriptions on grave markers evolved. The earliest examples were frequently plain and devoid of emotion, sometimes not even mentioning the animal’s name.

Before long, they’d become the exact opposite.

“Let a little dog into your heart,” reads a headstone for a pooch named Bingo in Atlanta’s Pet Heaven cemetery, pictured in the book, “and he will tear it to pieces.”

A different kind of loss

“I miss your snoring every night. I miss your wet nose kisses. I miss seeing your big beautiful eyes.”

“If Christ would have had a little dog it would have followed him to the cross.”

“You came into this world the day my beloved son left. You, sweet girl, saved my life.”

“Our best loved baby.”

“Mommy’s favorite ‘face’”

You don’t have to have ever known Snowball Rodrigues, Bandit Kornada, Muffin Zahnow, Beer the police dog or any of the hundreds of other pets interred at the Craig Road Pet Cemetery to feel the pain of their passing etched into their gravemarkers.

Visiting a human cemetery tends to be a tranquil, solemn experience, the dead often memorialized with spare, poetic prose carefully chosen to distill a person’s essence.

Strolling the grounds on a recent afternoon feels entirely different. Here, among the heart-shaped tombstones for canines Blush (“Daddy’s girl”) and Meritage (“Her smile will never fade”) and the wreath of orange flowers brightening the grave of pitbull Knight Haneefzai, the emotions are writ large and shared without inhibition.

In terms of grieving, the difference between the two is the difference between a whisper and a shout.

As Koudounaris writes in “Faithful”: “Inscriptions on pets’ grave markers speak in their own peculiar idiom, free from the restraints that govern our discourse over the human dead.”

But why?

The answer to this question lies at the heart of his book.

“It’s a different kind of relationship,” Koudounaris explains of the dynamic between human and pet. “Throughout their lives, even your most beloved friend is still a discrete individual, but that cat or dog becomes a part of you.

“Losing a person can be like losing a piece of yourself, but in a different way,” he continues, “because a pet becomes a part of our identity in a very intimate way. And because it’s an unspoken relationship, it’s almost like a primal, intuitive relationship rather than a rational one.”

This is what can make the relationship such a powerful one.

“It’s the unconditional love from the pet,” explains Dr. Birgitte Tan, a Henderson-based pet loss and grief specialist and retired veterinarian. “They don’t talk back, they don’t argue, they are just there for us, so we feel that they give the love without fear, without worry, without policing.

“We can have such a deep bonding,” she continues, “because they’re not sitting there saying, ‘I’m wondering if you’re going to receive my love or reject me.’ They just give.”

Gone but never forgotten

On the very last page of “Faithful Unto Death,” there’s a small photo of a cat’s grave in Winterhaven, California, ringed by a bag of Fancy Feast cat treats, a jar of catnip and a small statue of a winged feline.

“A calico, not a tortie, get it right!” its inscription reads.

The cat, named Tika, belonged to Koudounaris.

She died in 2017, while he was writing the book.

Koudounaris is facing loss once more in Baba’s passing.

With “Faithful,” he digs deep into the pet grieving process — a process that remains ongoing for him.

“Countless books have been written about grieving your pets, and I read every single one of them to help me know what I didn’t want to do,” he says. “One thing I came away from after talking to people whose pets have passed, and after reading all those books, it’s that every relationship with a pet is different — the grief is vastly different, and no one can really guide you through it.

“What I wanted for this book was this additional level, where it also served as a kind of grief — not guide or template — but just something to help people understand that their feeling was universal,” he continues. “This is a universal problem, and you’re okay for feeling it.”

Back at Craig Road Cemetery, a man in a black shirt and matching ball cap sits cross-legged before a fresh grave, dabbing his eyes with a white cloth as he lays a pet to rest.

He has another dog with him, a small, excitable thing on a leash.

As he walks off the grounds a few minutes later, he coaxes the dog to jump in the air, a moment of sadness giving way to a moment of play, the pain of owning a pet giving way to its joys.

“This is the essence of memento mori, the reminder of death,” Koudounaris says later. “It’s also memento vitae: the reminder of life.”

Paul Koudounaris hosts a book signing and lecture for “Faithful Unto Death” at 7 p.m. Saturday at Cemetery Pulp (3950 E. Sunset Rd, Suite 106).

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram.