With summer heat gone, proper hydration is still essential

Tara Pike wants to divert some plastic bottles from the local landfill. The University of Nevada, Las Vegas’ sustainability coordinator estimates that only about one in four plastic water bottles makes it into the recycling bin. This year the goal is to change that, at least on the university’s campus. With Pike’s help, the school has been installing hydration stations since last spring. The water stations bring carbon-filtered water into or near buildings on campus as an alternative to traditional drinking fountains.

The stations also have special spigots that let students and employees fill their own bottles. Early input has students saying the water tastes better than tap water, but not quite as good as actual bottled water, most of which is processed by reverse osmosis.

But the effort, which now counts about 21 stations on campus and another seven or so coming on line by year’s end, may also help to bring added hydration benefits to students and staff. Thousands of gallons of water have been used so far, as more and more campus regulars are starting to fit water stops into their daily routines.

“It’s not just students,” Pike said. “It’s the grounds crew and staff that tell me they use them all the time.”

Tedd Girourd, a kinesiology professor and director of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas’ athletic training education program, uses the stations daily to fill his own water bottles.

“Before, with water fountains, I just didn’t see them as sanitary,” he said.

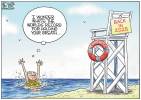

Although the school expects a drop in hydration station use with cooler weather coming, Girourd hopes for the opposite. As cooler weather sets in, the exercise expert knows this is the time when many valley residents may forget to bring water on that hike or jog where they would have certainly done so in August.

Dehydration is no laughing matter. Studies have shown that about 75 percent of the U.S. population is in a perpetual state of dehydration and probably doesn’t know it.

“It’s like anything else that builds up, you assume a threshold and people don’t realize how they’re supposed to feel,” said Marjorie Nolan-Cohn, a registered dietitian and spokeswoman for the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics.

Heat-related injuries climbed 133 percent between 1997 and 2006, according to the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Nearly half of those involved youths. In the past five years, the number of heatstroke deaths for overexerted youths is five times higher than in any five-year period during the past 35 years, says Douglas Casa, a professor and heat stroke expert at the University of Connecticut.

THE BODY’S NEEDS

Depending on activity level and other factors, suggestions on the amount of water a person needs can vary widely. Nolan-Cohn tells her clients that drinking half one’s body-weight in ounces is a solid rule of thumb. For example, a 200-pound person should consume 100 ounces of water in a day. The dietitian also says clients are always surprised at how much positive change occurs by simply drinking more water.

“Clients come in all the time and are shocked by how much better they feel. Their skin clears up and they have energy,” she said.

Girourd, whose work primarily involves competitive athletes, uses weigh-ins before and after workouts or competitive events to gauge an athlete’s hydration level. For each pound of weight lost in a workout, an athlete needs about 16 ounces of water to replenish the system. Once someone loses 2 percent of body weight, performance is affected. A 300-pound football lineman, for example, could lose 15 pounds in a strenuous workout, he added.

“You want to drink ahead of the thirst. That’s a difficult message to get across to people. But with athletes when you tell them (dehydration) will directly impact performance, they get it,” he said. “It doesn’t take much to lose 2 percent, especially in this climate.”

SYMPTOMS

Girourd also encourages athletes to take a more personalized approach to assessing their hydration. Charts are hung in athletic facility bathrooms at the school that show the color of healthy urine. A light yellow color usually means proper hydration. A darker, more apple juice-looking urine signals dehydration. Some athletes who are experiencing constant dehydration will have gastrointestinal problems, too, Girourd said.

Nolan-Cohn also said dehydration can bring a strong smell to urine. Other symptoms to watch out for are: not going to the bathroom all day, slow muscle recovery, leg cramps, soreness, headaches, dizziness, water retention (puffy fingers and legs), hunger or sugar cravings not long after eating, and fatigue.

One reason for decreased energy in a dehydrated person is the impact on the heart. Dehydration creates a lower blood volume in the heart, forcing the organ to work harder. The heart may add three to five extra beats per minute for a dehydrated person, Girourd noted. It’s not a huge factor for the everyday person, but, again, when dealing with athletes who feel fatigue, motivation to rehydrate sets in.

And, as Nolan-Cohn explained, even everyday people can feel an energy boost just by being properly hydrated and having their hearts not working as hard.

Girourd also points out the importance of acclimatization. This is an issue particularly for sports teams that visit the valley from more traditional four-season environments. He said it really takes about 14 days for a body’s thermal regulatory system to adjust to the climate shift.

But the information also applies to local students coming back to school for fall sports after being indoors much of the summer avoiding heat. As a result, local high school fall sports teams limit the length of training sessions for the first two weeks of training, Girourd said.

SPORTS DRINKS, ELECTROLYTES

Sports drink sales this year climbed to more than $4.1 billion though April, a State of the Industry analysis from Beverage Industry magazine showed. That may sound a bell for profits, but it’s not all in the good name of hydration.

Marketing teams have brilliantly targeted children with new logos and ever-changing drink colors. And they may be trying to sell children something they don’t need.

Athletes competing at a very high level may need the glucose and electrolyte minerals, such as sodium and potassium, that are in present in sports drinks. But kids and people playing recreational sports may not need the kind of boost, or the calories, sports drinks pack.

Chris Salas, a local personal trainer, asserts that water is the ultimate nourishing agent, not the colorful sports drinks so many kids are enjoying. He said even drinks such as Vitamin Water are not all their marketers claim them to be.

“They’re not squeezing fruit into those bottles. They’re using a chemically engineered fruit-flavored product and it’s nothing like water and fruit,” he said.

Salas said if someone is dehydrated in the middle of a workout, particularly someone with low blood sugar, a small amount of juice with plenty of water is a better cure. In intense athletic training situations, Girourd highly recommends a sports drink. But for the normal person on a 2,000 calorie-a-day diet, he uses some common sense.

“I say, ask yourself: ‘Does that (number of calories) play into your normal caloric intake level?’ ” he said.

But while Girourd isn’t against sports drinks as much as Salas, he also believes the industry’s marketing is misrepresenting the drinks. One egregious example is in public schools, where many cafeterias have ditched sodas in vending machines and replaced them with bottled water and sports drinks.

“Schools are thinking Gatorade is a health drink and that’s not accurate,” he said. “It’s absolutely what athletes need, but it’s not what the sedentary person needs.”

But Girourd also said it’s important to address the common knock against water: taste. Diluting a sports drink is one answer. That way a little taste is given to the drink without the heavy calorie and sugar intake. But Girourd has also found through research that water temperature between 50 and 59 degrees is ideal enough to satisfy the taste problem, too.

“Research shows people prefer the cooler temperatures for their drinks, and it works,” he added.

There are also hydrating food options. Fruits and vegetables are made up primarily of water in the first place. And with the many vitamins and minerals naturally contained in them, these foods are a better electrolyte enhancer than any drink on the market, Salas said.

“I highly recommend watermelon to my clients,” he added. “It’s hard to beat.”

COFFEE CONFUSION

For years, health experts counted coffee as a diuretic. More recent research is indicating that it may not be after all.

And now more and more athletes are looking to caffeinated substances before competition to give that extra boost, too. Experts appear to be proceeding with caution on the subject. For Salas, who himself is a coffee lover, he counterbalances water intake with a coffee beverage and encourages clients to do so, too.

Girourd said carbonated beverages are a bigger problem than coffee. They delay gastrointestinal emptying and can bring an uncomfortable feeling of fullness while exercising, he noted.

“Those are the drinks you really need to avoid,” he said.