UMC can’t afford to help deaf with cochlear implants

The big brown eyes of 2-year-old Anahi Hernandez focus on the hands and lips of speech therapist Jenny Noble, who is teaching the pretty little deaf girl the sign language for “all done” as they finish playing with a ball.

Noble’s hands are in front of her chest, palms facing in, fingers pointing up. Then she turns her hands with a quick movement with her palms facing out.

“All done,” Noble says, repeating the sign.

In imitation, Anahi flips her tiny hands with a smile that grows each time she does it.

Her mother, Maria Rosales, sits nearby in the therapy room. Proud of her wordless baby girl, she applauds.

And then, with tears in her eyes, Rosales quietly bows her head and says a silent prayer.

What she prays for during each therapy session at the South Rancho Drive office of Hope Communication and Feeding Specialists is that her only child won’t have to rely just on sign language to communicate.

“Dr. (Matthew) Ng says that with a cochlear implant she’d probably be able to learn to hear and talk,” Rosales said. “But now no hospitals in Las Vegas are doing the operations because Medicaid and insurance won’t pay enough for them. I pray my daughter doesn’t have to be deaf for life because of money.”

AN EXPENSIVE MIRACLE

Divine intervention could be what is needed to keep Anahi, a Medicaid patient, and dozens of other Nevada children and adults from an unending sound of silence, now that officials at University Medical Center, the last hospital in the state to offer the implants, have said it is has become financially impossible to continue the cochlear implant procedures.

There also is the possibility, however remote, that Anahi and others without high reimbursement insurance plans could have their procedures done at private ambulatory surgical centers, which are just beginning locally to enter this surgical arena.

For that to happen, manufacturers of the implants will have to dramatically cut their prices, said Dr. Rudy Manthei, president of one of the centers.

UMC administrators said that’s something manufacturers have been unwilling to do for their patients.

Sometimes called a “bionic ear,” a cochlear implant is an expensive device — the apparatus alone costs more than $30,000 — that helps overcome problems in the inner ear, or cochlea. The surgical procedure for just one ear costs nearly $50,000 and takes two to four hours.

According to the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, the total cost of a cochlear implant, including evaluation, surgery, device and rehabilitation, can be as much as $100,000. Insurance seldom picks up the total cost.

Talk show host Rush Limbaugh can hear because of the technology. So can former Clark County Commissioner Bruce Woodbury, who calls the implants “a miracle” and “absolutely essential” for deaf children whose condition can be helped by the device.

“We lost nearly $800,000 in the last two years doing the cochlear implants,” said Kim Voss, an associate UMC hospital administrator. “It was a very painful decision to stop them a few weeks ago. It’s not something we wanted to do. We have a mission of helping here that we take very seriously. But the reimbursement from the government and insurance companies, especially Medicaid, is way too low. We couldn’t absorb the losses when we’re asking employees to take a pay cut and the hospital is losing $70 million a year.”

Sunrise Hospital, the other hospital that had regularly performed the procedure, backed off the implants in 2008.

“Our reimbursement didn’t even cover the cost of the implant and the supplies to perform the procedure,” said Sunrise spokeswoman Stacy Aquista. “It is no longer financially viable for Sunrise to offer the procedure.”

nevada’s situation

To hearing specialist Ng, one of about five physicians who perform the implant procedure in Las Vegas, the halt of the procedures could mean the state “is going to see a slew of deaf children, and that’s going to cost us a lot more in the long run. Believe me, it will tax the school system, and later it can hurt them from living productive lives.”

About 70 percent of Ng’s cases involve Medicaid patients.

He says he has about 10 cases backed up, and says the other specialists have similar numbers of patients waiting.

“The newborn hearing screening done of children in the state finds many cases,” he said.

Why UMC finally had to throw in the towel on the procedures isn’t difficult to understand.

In the 43 cases done in the last two years, the cost of the procedure came to about $48,500. Yet in the 14 cases that were reimbursed by Medicaid, the health program for the poor that is state-managed but jointly funded with the federal government, records show UMC received only $16,969.78 per procedure, a loss of more than $31,500 per case.

“Just the device alone costs us $33,000,” Voss said. “And then there’s the cost of anesthesia, nursing care and so on.”

Medicare reimbursed UMC at just more than $34,300 per case — the hospital still lost more than $14,000 on each one — while private insurance reimbursed the public hospital at around $39,000, cutting the loss to about $9,500 on each case.

States set Medicaid payment rates within broad federal guidelines, with some states having higher reimbursement rates than others for procedures.

Faced with huge financial problems in recent years, many states, including Nevada, have reduced Medicaid payments to health care providers. In 2008, Nevada’s hospitals suffered a 5 percent cut.

Had the Medicaid reimbursement for cochlear implants been around that of Medicare or commercial insurers, it is possible that UMC could have continued the program.

Administrators of public hospitals, trying to be faithful to a mission to aid the unfortunate, often take losses in some care areas if they can be made up in a more profitable program line, such as heart surgery.

“The losses were just too big,” Voss said. “We started looking at this in 2006 and again in 2008, and there was an outcry from physicians and families, so we continued. But it can’t be done any more.”

That Nevada state Medicaid offers so little in reimbursement makes Ng, who says about 80 percent of the children who need the device are on Medicaid, ask these questions of political leaders: “What does our society value? Are we unnecessarily diminishing quality of life?”

Lynn Carrigan, an administrator in the state’s division of health care financing and policy, said the state had recently raised the Medicaid reimbursement rate for the implants to around $19,000 per case, still far less than what UMC administrators say they need to break even.

“I didn’t know they had stopped the procedures,” Carrigan said. “That’s too bad.”

Even if a patient has the insurance or the money to have the procedure done at UMC, it can’t be done.

Federal guidelines don’t allow a public hospital to “cherry pick” its patients, Voss said.

“Ethically if we can’t serve Medicaid patients, then we’re not able to serve anyone else,” she said.

That means that although Maria Guillen has insurance through the Culinary union, she can’t get the procedure at UMC for her 2½-year-old son, Oscar.

“My husband also has insurance through his construction job,” she said. “We’ve been waiting for months now. We’re so worried. It’s much better if your child gets the device when he is very young.”

Now that ambulatory surgical centers will be doing implants, Ng said he is checking to see if the Guillens’ insurance would be accepted there.

The Guillens are also exploring the possibility of going out of town for the procedure.

WHO CAN BENEFIT

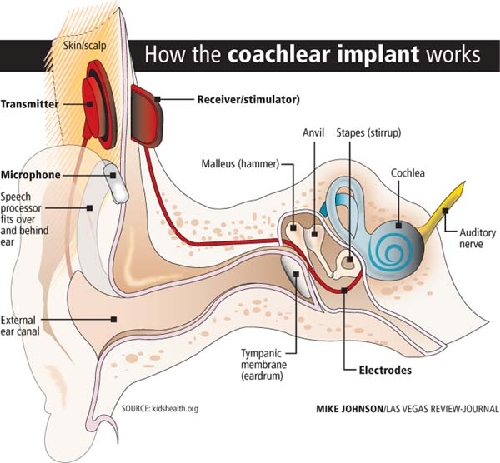

A cochlear implant is not at all like a hearing aid, which just amplifies sounds so they may be detected by damaged ears. A hearing aid does not help the profoundly deaf.

The implant bypasses damaged portions of the inner ear, using its own electrical signals to stimulate the auditory nerve. It allows people to hear, though the sound quality is sometimes described as “mechanical.”

Coupled with intensive post-implantation therapy by speech language pathologists and audiologists, which isn’t always covered by insurance, cochlear implants can help young children acquire speech, language and social skills. If possible, it is better to have it done by age 2, Ng said, although children often get them until age 6.

Early implantation provides exposure to sounds that are helpful during the critical period when children learn speech and language skills.

Many adults who have lost all or most of their hearing later in life often can benefit from an implant. They learn to associate the signal provided by the implant with remembered sounds, allowing recipients to understand speech by listening through the implant, without requiring lip-reading or sign language. Again, therapists generally become part of the learning equation.

Woodbury, who said he has a condition that started to rob him of hearing in his 20s, got his first implant about a decade ago at UCLA. A few years later, he said, Ng implanted a second one in the other ear at UMC.

“Having two of them helps with background noise,” he said.

Ng said he usually implants one device first to see how the patient responds and then later implants a second.

“Research is showing that people are doing better with two of them,” he said.

Woodbury said he finds it distressing that UMC has had to stop the procedures.

“I’m so grateful I have them,” he said. “I thank God and the medical profession. I couldn’t hear without them. I think it’s a miracle. It has allowed me to lead the life I have. I’m fortunate I didn’t have a financial difficulty in getting it done.”

Woodbury said it is inconceivable to him that the implants are still considered elective surgery.

“To someone who is deaf, it is a necessity,” he said. “For a child starting out in life, I think it is absolutely essential.”

Not all deaf individuals qualify for an implant. Reasons include: The hearing loss does not involve the cochlea or inner ear; an individual has experienced profound deafness for a long period of time; the hearing nerve itself is damaged or absent, and a hearing aid still allows a person to hear some sound and speech.

Ng said he suspects the cost of implants has a lot to do with how many people get them. According to the FDA, approximately 219,000 people, including about 70,000 Americans, had gotten them as of 2010. Yet a 2003 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine set the number of potential U.S. implant candidates at 1 million, and an estimate by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders put the figure at seven times as many,

“Money is playing a factor, but I don’t know how large,” Ng said.

Taci May’s 4-year-old daughter, Khloe, received an implant about two years ago.

“It’s been a miracle for our family,” May said. “The therapy is a lot of work, but we’re hoping she’s going to be all caught up on her speech by kindergarten or first grade.”

Just how often those miracles continue to play out in Las Vegas seemingly depends on how well ambulatory surgical centers can negotiate with the vendor for the cochlear implants, said Manthei, president and CEO of the Seven Hills Surgery Center in Henderson.

“We’ve been trying to work with the company (Cochlear Americas) to lower the implant cost,” Manthei said. “Manufacturers continue to increase the cost of implants and materials even in this economy, when things are so tough for everyone. What you’re seeing now is people losing access. … Of course, we’d like to be able to do Medicaid patients. But something would really have to change in reimbursement.”

Though Mike Blanton, area manager for Cochlear Americas, said he is sure something can be worked out so that even Medicaid patients can be done at ambulatory surgical centers, UMC’s Voss remembers a man who wouldn’t negotiate.

“UMC wanted too much of a discount,” Blanton said, not willing to say how much profit on the device is enough for his company.

May, whose daughter is now doing well after her implantation at UMC, can’t believe other parents may not be able to help their children.

“It breaks my heart,” she said. “It’s a life-changing thing. You open up so many more opportunities for your child.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at

pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.