Rise in esophageal cancer may accompany the ‘good life’

Taking heartburn seriously could save your life.

That’s true even among those who seem otherwise healthy, according to Dr. Fadi Braiteh, a gastrointestinal oncology specialist with Comprehensive Cancer Centers of Nevada. When those patients come to see him for cancer treatment, what’s sad, in retrospect, he said, is their assumption that heartburn is necessary.

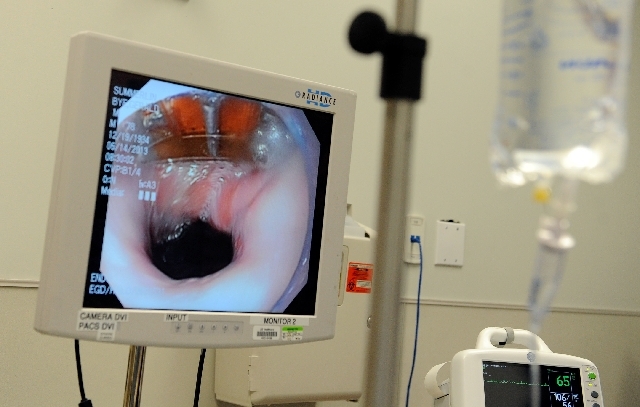

“Heartburn is not the normal condition,” he said. “They truly need to talk to their primary care doctor to see the gastroenterologist, have a scope. Because unfortunately, often I see patients and I wish they did the scope six months earlier, nine months earlier. That would have been a lifesaver.”

Heartburn, or reflux disease, involves the reflux of acid up from the stomach, burning the esophagus, the hollow tube that moves food and liquid from the throat to the stomach. Reflux problems may be associated with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, a kind of esophageal cancer.

According to the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, esophageal cancer, overall, is on the rise in Nevada, based on statistics taken from 2005 to 2009. Death rates are rising in Clark County. And, Braiteh said that the trend is becoming a “worrisome public health issue” across the country.

“There are three cancers increasing nationwide in the United States, while all others are going down,” he said. Liver cancer, melanoma and gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma are at the top of the list, not necessarily in that order.

Linda Ivers is a local American Cancer Society patient navigator and human Yellow Pages of resources ranging from free gasoline cards to support groups for people as far away as Kingman, Ariz. She said she saw more than 1,600 patients with all kinds of cancer, communitywide, last year alone. She’s also seen a rise in the number of people struggling with esophageal cancer.

“I wouldn’t say that it’s skyrocketing, but I have seen more of it than I have in previous years,” she said. “I would say 40 percent more in the last two years.”

Esophageal cancer comes in two “different flavors,” Braiteh said. Squamous cell carcinoma, in the family of the head and neck cancers, is associated with smoking and drinking, and usually happens at the upper or mid third of the esophagus. Adenocarcinoma develops at the stomach-esophageal junction, he said.

Thirty years ago, 95 percent of esophageal cancers were squamous, with adenocarcinomas accounting for 5 percent, he said. But adenocarcinomas are galloping forward with a vengeance, moving the balance toward 60/40.

“There is a suspicion that it’s related to obesity, and the subsequent heartburn that comes with obesity,” he added.

Although diabetes, cardiovascular disease, strokes and heart attacks are the widely known malevolent fruits of obesity and the American way, now add another, more mysterious killer to the basket.

“Even now, with medicine improving the survivorship of patients with these conditions, they’re again falling into the trap of this consequence of obesity, which is cancer,” he said.

Braiteh sees approximately 20 new esophageal cancer cases per year, he said. If they undergo the recommended surgery, chemotherapy and radiation while the disease is localized, their chances of reaching a five-year survival mark are 1 in 3, he said. At stage 4, when the cancer has spread, it’s 1 in 20.

“For adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, it’s not a good prognosis,” said gastroenterologist Dr. Navjot Singh of Red Rock Gastroenterology. “Squamous carcinoma has a better prognosis because it can be treated differently.”

As for warning signals, watch out for heartburn, especially after eating or spontaneous activity, Braiteh said. That includes the burning sensation of acid going behind the chest bone. Or, waking up at night with heartburn and the sensation of acid traveling up the throat. Among the later warning signals are the sensation of food stuck in the throat and pain when swallowing.

“Not every one of those pains means you have cancer, but the likelihood becomes exponentially high,” he said, adding that people need to talk to their doctor.

According to the National Cancer Institute, weight loss, hoarseness and coughing can be signals as well.

Drinking hot tea and hot alcohol, a more widespread practice in nations such as Iran and France, can also burn the esophagus, leading to the squamous diagnosis, Braiteh said. And, genetics may make a difference — one possible reason why esophageal cancer looms even more darkly in Japan than in the U.S., according to Braiteh.

Singh suspects that Las Vegas may provide a playground for esophageal cancer.

“It’s a different lifestyle,” he noted. “People drink and smoke here a lot. And they eat a lot. I think that’s because of the availability of these products, and the service industry. I don’t think I saw this much smoking and drinking where I trained.”

In his 3½ years of practice in Nevada, he’s seen plenty of esophageal cancer and Barrett’s esophagus, a condition that can lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Barrett’s snuck up on 78-year-old Jerry Bye, one of Singh’s patients and a former Boeing test engineer and contracts manager for 35 years in the Seattle area. After moving to Las Vegas to enjoy retirement 15 years ago, Bye realized that the economy wouldn’t cooperate. He returned to work as a school bus driver.

He could tune the kids out. But 10 years ago, he began waking up in the middle of the night with a hot sensation in his throat.

“It wasn’t painful or anything,” he recalled. “It was just annoying.”

His doctor diagnosed him with Barrett’s and put him on a stomach acid suppressant for several years. Things changed when Bye switched to Singh last year.

According to Braiteh, acid can transform the lining of the esophagus into something akin to the lining of the stomach. The tissue becomes unstable, and the end result is Barrett’s. Lifting and stripping the area allows a new lining to grow — like skin molting and making room for new skin.

Enter Singh, who uses a Halo System at Summerlin Hospital Medical Center to help Barrett’s patients ward off cancer with a radiofrequency ablation procedure. So far, he said, he’s performed more than 50 of the procedures in the Las Vegas area.

“This is something new to Nevada,” he added. “Summerlin has made the choice to go forward with the investment in treating patients and preventing cancer, and I think they’re thought leaders here.”

Bye’s third, and he hoped final, procedure was on June 14 at Summerlin Hospital. By now, he knows the ropes of a process that has involved a probe going down his mouth and throat. The before and after photographs of his insides have been impressive, he said. And, he reckoned, the procedure has usually taken less than an hour.

Although he hasn’t noticed a difference made by the procedures, he’s grateful that Singh switched his prescription, a move that’s cleared up the reflux. What he has gotten from the procedures: the hope of gaining proof on the final round that the Barrett’s, and the possibility of cancer, are gone.

But for those who do develop esophageal cancer, a lack of resources, funding and knowledge specific to their cancer presents a mighty obstacle, according to Ivers.

“Do you ever think of esophageal or throat?” she said. “People say, ‘Oh, I’ve got a lump in my throat.’ And they just ignore it.”

When Ivers’ own mother showed up at her house with a lump on the back of her neck, Ivers sent her to the doctor — where she was “pooh-poohed.” But in 2½ hours, the lump changed dramatically, she said. Her mother was diagnosed with stage 3 esophageal cancer, and lived for almost three more years, although she’d been given three more months.

“Nobody talks about any other cancer except for breast and maybe prostate,” she said. “That’s a fact. I think it’s very sad that the other cancers aren’t recognized. But it takes one person to champion that cancer.”