Researchers say Alzheimer’s studies must focus on abnormalities in patients’ brains

A normal human brain, what most of us carry around in our heads, is the size of a large grapefruit but looks like a large pinkish-gray walnut. Doctors who have held the organ say it feels soft and squishy.

For most of her 83 years, before she started exhibiting major symptoms of brain-killing Alzheimer’s disease three years ago, Verna Kinersly’s brain operated normally, which is to say, amazingly.

What scientists estimate as 20 million billion bits of information move around in a normal brain every second, which enabled her to think, move, see, hear, taste, smell, create and feel emotions.

Without her asking, her brain also stored memories, controlled every heartbeat, breath and blink. It also received and analyzed information, so as a young mother, when she saw her daughter falling face first out of a chair across the room, she knew just how fast she needed to run to save her.

Today, her diseased brain doesn’t analyze situations well enough for her to safely walk across the street.

That so much of human life is often mysteriously controlled by something so small —- within the normal 3-pound brain is more power than in any supercomputer —- prompted Nobel laureate James Watson, co-discoverer of DNA’s structure, to call the human brain "the most complex thing we have yet discovered in our universe."

No one still knows how the brain coordinates myriad processes and assimilates vast amounts of information to function as an integrated whole.

LOOKING FOR A BREAKTHROUGH

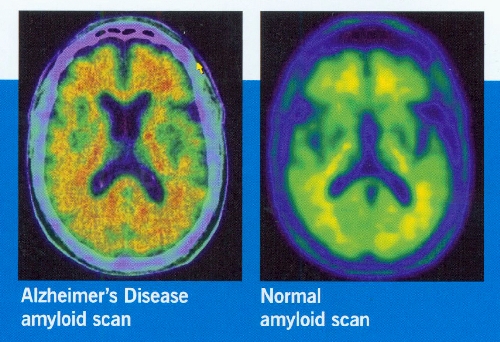

It’s morning at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, where director Dr. Jeffrey Cummings recently acquired medicine’s most sophisticated brain imaging protocol for Alzheimer’s, enabling researchers, for the first time, to detect the disorder at the earliest sign of memory problems. It’s an advancement that could lead to accelerated treatment and development of drugs against the disease.

Jerry Kinersly, a retired banker with a scientific bent, sits inside the center with his wife and talks about how the complexity of the brain undoubtedly plays a role in the difficulty researchers have had in unlocking the baffling workings of Alzheimer’s.

Kinersly, 83, says his wife, currently enrolled in a clinical trial, desperately wants to be part of a research breakthrough into the incurable disease, what most clinicians say is the only real hope for ameliorating the disorder’s devastating human destruction.

About 5.4 million people in America have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and the number is expected to increase to 16 million by 2050. Alzheimer’s Disease International estimates there are more than 35 million living worldwide with dementia, and that could increase to 115.4 million by 2050.

"It’s not only terribly costly in human terms, but it can bankrupt the country," Kinersly says, noting that his wife, who is losing her speech to the disease, volunteered to be part of a clinical trial not only to help herself, but all of mankind. "I know helping mankind may sound corny, but that’s how we feel. We believe finding answers to this disease are that important both on the human and economic front."

Experts project health care costs for the disease in the U.S. to hit $1.1 trillion in 2050.

While the National Institutes of Health spend annually $450 million on Alzheimer’s research, cancer research totals more than $6 billion a year, heart disease $4 billion and HIV/AIDS $3 billion.

Given the devastation caused by Alzheimer’s, the research funding allocation for the disease stuns Kinersly.

"It’s kind of hard to believe," he says.

Larry Ruvo, one of the nation’s top private fundraisers for brain research and the man who built the center in honor of his father, Lou, who died of Alzheimer’s, puts it another way.

"The amount of funding we get to end this tsunami of a disease is disgraceful," he says. "It’s time for people to stand up and say so to their elected representatives."

PLAQUES AND TANGLES

Like so many research trials with participants around the world, the one Verna Kinersly is in supports the still unproven but prevailing theory that the chief blame for driving the disease falls on the beta-amyloid protein, which forms sticky plaques and kills brain cells in sufferers.

Her 18-month trial treatment involves active immunization, using a type of vaccine that theoretically will trigger the body’s immune defense against beta-amyloid.

The National Institutes of Health report that more than 50,000 volunteers, both with and without Alzheimer’s, are urgently needed to participate in more than 175 trials and studies in the United States, 25 of them at the Ruvo Center. Dr. Kate Zhong, the center’s senior director of clinical research and development, points out that is more than any other center has in the country.

Studies nationwide generally deal with possible causes and risk factors of Alzheimer’s, as well as trials of drugs and behavior modifications aimed at treatment, prevention and improving diagnosis.

More than a century has passed since German physician Dr. Alois Alzheimer first described abnormal deposits of beta-amyloid protein plaques and tau protein tangles in the autopsied brain of a woman who suffered with dementia.

Now the most common form of dementia, Alzheimer’s stands as the only cause of death among the top 10 in the U.S. without a means to prevent, cure or even slow its progression —- a fact made less surprising by scientists admitting more was learned about the brain in the past 25 years of the 20th century, largely because of advances in techniques and imaging technology, than in all of previous human history. One out of eight people 65 and older —- 13 percent —- currently has Alzheimer’s.

Both Cummings, one of the world’s most renowned researchers, and William Thies, chief medical and scientific officer for the Alzheimer’s Association, agree that there is good reason the abnormal deposits described by Alzheimer still garner the most attention by researchers: The brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease are often riddled with plaques and tangles, which many scientists believe are linked to the development of the degenerative dementia.

The two methods being pursued to prevent the formation of plaques, where drug companies have spent the most money —- billions —- are vaccinations and drugs.

A string of experimental drugs designed to attack beta-amyloid have failed recently in clinical trials, leaving some drug company executives wondering whether they should cut research funding for plaque and boost funds for more research into tangles, which has had mixed results in the past. The work of Australian researcher Dr. Claude Wischik, who fervently believes tau is the cause of the disease, has served as a catalyst for many companies to invest hundreds of millions in drugs to stymie the protein. Wischik is awaiting the results of a clinical trial testing his causation theory.

Still, this spring U.S. officials said they would help fund a $100 million trial of the Roche pharmaceutical company’s amyloid-targeted drug, crenezumab, in 300 people who are genetically predisposed to develop early onset Alzheimer’s.

Research into both plaques and tangles, Cummings believes, needs to continue.

"We’re getting closer to real answers," he says as he sits in an office full of charts and studies.

Use of an imaging protocol that enables researchers to detect the beta-amyloid brain plaque, for the first time, early in the disease process is under way at the Ruvo Center. Cummings believes anti-amyloid drug trials have failed because patients enrolled in studies had progressed too far in the disease for treatments to be effective. A trial testing the accuracy of the scanner agent in the new imaging protocol is taking place in Las Vegas.

While insurance companies don’t cover the high cost of the test, Cummings believes the new imaging protocol will one day be widely used at the Ruvo Center and elsewhere to help make a concrete diagnosis. For now, he says it’s a research tool that will get new clinical trial drugs to patients earlier.

The center also has an anti-amyloid trial studying the efficacy of Bexarotene, an anti-cancer drug that also has shown promise against Alzheimer’s.

With several drugs failing to reduce the buildup of beta-amyloid plaques, it isn’t surprising, Cummings says, that research branches out into other areas, including surgical procedures that might boost memory and reverse cognitive decline.

Earlier this month, researchers at Johns Hopkins Memory and Alzheimer’s Treatment Center surgically implanted a pacemakerlike device into the brain of a second patient in the early stages of the disorder —- a form of deep brain stimulation similar to that already used successfully on thousands of Parkinson’s disease patients to reduce tremors and the need for medication.

Dr. Paul Rosenberg - head of the Johns Hopkins study, which also will involve 40 patients at three other U.S. sites and one in Canada – says he is heartened by a preliminary Canadian study that found that low-voltage electrical charges delivered directly to the brain 130 times a second over 13 months showed sustained increases in a patient’s glucose metabolism, an indicator of brain cell activity. Most Alzheimer’s patients show decreases in glucose metabolism over the same time frame.

Of the six patients studied in Canada —- those implanted do not feel the electrical current —- tests showed that two individuals appeared to have better than expected cognitive function.

Cummings says his biggest concern about deep brain stimulation for Alzheimer’s is that the disease is a widespread process in the brain, with the stimulation hitting only a localized area. It would be "very difficult to apply" such surgery to 5.4 million people with the disease, Cummings says, but he hopes making "drugs available to many people can be the way forward." If the surgery is positive in select patients, Cummings "would be delighted."

Both Cummings and Thies were excited last month by the findings of an English researcher who discovered a mutated gene, known as TREM2, that is suspected of interfering with the brain’s ability to prevent the buildup of plaque.

It is only the second gene found to increase Alzheimer’s in older people. The other, ApoEF, was discovered in 1993.

Both make a carrier of either gene three to five times more likely to increase the chances of developing Alzheimer’s.

The discovery, Cummings says, can provide clues to how and why the disease progresses, as well as open the door to a possible new drug to strengthen the gene, perhaps allowing the brain’s white blood cells to work.

PART OF AGING

Though in the distinct minority, there are researchers who believe that investigating the plaques and tangles in search of a cure for Alzheimer’s disease is a mistake.

"Old age is probably not curable," Dr. Ming Chen said recently in a wide-ranging phone interview.

Chen, who heads a research group at the University of South Florida, suggests that "tremendous social pressures" have pushed scientists to target Alzheimer’s as a curable disease. He says that as people live longer, Alzheimer’s researchers have been driven by the fear of the societal devastation caused by increasing numbers of dementia sufferers.

To Chen, Alzheimer’s appears an unfortunate part of aging for some people, just as some people suffer with osteoporosis and severe heart disease.

Writing in the December 2011 issue of the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, Chen said researchers should de-emphasize the quest for a cure —- he doesn’t think there is a villainous pathogen —- and instead search for effective prevention and treatment focusing on dementia as part of the aging process.

More studies, he said, should be done of interventions to strengthen or manipulate aging brain cells.

He stresses controlling risk factors, such as diabetes and hypertension, where studies have shown people are more vulnerable to developing Alzheimer’s.

What seems to support Chen’s position are study findings out of the University of California, San Francisco, in 2011. That report found that as many as half of Alzheimer’s cases worldwide could be prevented through lifestyle changes and treatment of chronic conditions such as diabetes. Even a 25 percent reduction in the seven risk factors —- depression, diabetes, smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyles, midlife high blood pressure and low education – could prevent 3 million cases of Alzheimer’s disease worldwide and nearly half a million in the U.S. alone, the study found.

Energizing the aging brain through social activities and educational opportunities can help fight off dementia, Chen says. He notes, too, that many older people live alone, hastening cognitive decline. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates 800,000 individuals with the disease, or one in seven, live alone.

Cummings also believes in a "use it or lose it" doctrine for the brain. He says a laid-back retirement might literally cause people to lose their minds. Quitting the world of meaningful work for a retired life of lounging around with a TV remote might seem enticing, he says, but that passive lifestyle is increasingly seen by researchers as a high risk factor for Alzheimer’s.

It is time, Cummings says, for the nation’s top governmental leaders and public health officials to have a frank discussion about the implications of retirement and a disease for which age is unquestionably a risk factor.

"We have a social idea of what retirement consists of, and we need to re-examine that idea," he says. "The logical extension of the data we have on dementia is that a person who is still capable of working, who is mentally stimulated with a strong sense of purpose, is better off from the cognitive point of view continuing to engage in that position."

TIMING MATTERS

Early onset Alzheimer’s, in which genes have proven to be a major factor, should be treated differently from the more common form of the disease, which often strikes people in their 60s and beyond, Chen says. About 5 percent of Alzheimer’s patients get the disease before their 60s.

Chen says medical interventions still should be found to deal with the three acknowledged genes that carry mutations causing early onset Alzheimer’s: APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2.

Cummings and Thies strongly disagree with Chen’s contention that the older age Alzheimer’s is a normal part of aging. While they acknowledge that there may well be multiple factors causing the condition, including genetics and lifestyle, they also believe researchers are zeroing in on slowing the molecular process at the heart of Alzheimer’s.

It is also clear, Cummings says, that stem cell research might play a role in Alzheimer’s treatment.

Scientists at the University of California, Irvine, have found that neural stem cells can rescue memory in mice genetically engineered to have advanced Alzheimer’s, raising hopes of a potential treatment.

CLINICAL TRIALS

Neurologist Dr. Charles Bernick says he has been moved by the fact that hundreds of Southern Nevadans want to be part of clinical trials: "They know what they’re testing probably won’t help them, but they really do want to help others."

They are people who include 85-year-old Richard Parker, who power walks five miles a day and does 200 curls with 10-pound dumbbells. He was part of a study that tested a pill he took three times a day for his short-term memory problems. The pill turned out not to be effective, but he thinks the exercise is.

"We have a center in this town doing research dedicated to stopping Alzheimer’s," he says. "Why wouldn’t people want to support it? You might want to help yourself and other people as well."

Currently ongoing at the Ruvo Center is the first multisite clinical trial in the United States aimed at trying to identify Alzheimer’s disease through an inexpensive blood test.

A successful trial could be a precursor to detecting the disease before memory loss occurs, a big step toward allowing earlier therapeutic interventions to halt or stabilize progression of the disease.

Another unique trial investigates the efficacy of a chair developed by the Israel-based company Neuronix. The chair combines mental exercise and transcranial magnetic stimulation in the hopes of improving brain function.

New drugs to be studied, some of which involve memory testing, blood tests and brain imaging, include:

■ Takeda, an oral tablet designed to delay the onset of Alzheimer’s.

■ IGIV, an intravenous drug that could slow the progression of the disease.

■ Biogen Idec, another intravenous drug study of a medication aimed at slowing disease progression.

■ Avanir, testing of a drug that has shown early promise of treating agitation and other behavioral problems in Alzheimer’s patients.

■ Resveratrol, testing of an active ingredient in red wine, one found to have potential in slowing the disease.

Both Cummings and Thies say there is a greater sense of urgency among researchers since President Barack Obama signed the National Alzheimer’s Project Act into law last year.

It calls for scientists to find a way to treat or prevent the disease by 2025, a goal some experts feel is too ambitious.

The five drugs currently approved by the FDA for treating the cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease —- Namenda, Razadyne, Exelon, Aricept and Cognex —- hit the marketplace between 1993 and 2003.

In its attempt to see the 2025 goal is realized, the Obama administration plans to spend an additional $156 million over the next two years.

Philanthropist Ruvo calls it "far too little … it makes no sense considering the devastation of the disease."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@ reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.

Alzheimer’s disease: A Rising StormThe Review-Journal presents a series about Alzheimer’s disease and its impact on society, today and potentially in the future.

• An overview outlining the prevalence of the disease and efforts by families to cope with it and by researchers to treat and cure it

• The financial impact of the disease on families and society

• Challenges for the 80 percent of Americans who choose to care for their loved ones with Alzheimer’s disease at home

• Alternative forms of care, from day care to assisted living and nursing homes

• Identification and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

• Debate about the benefits of testing for Alzheimer’s

FINDING HELP

These are local organizations that help people with Alzheimer’s disease and their families. Some accept volunteers.

Alzheimer’s Association, Desert Southwest Chapter, Southern Nevada Region

The association offers general information, support groups, educational programs, referrals and opportunities to volunteer.

Address: 5190 S. Valley View Blvd., Suite 104, Las Vegas, NV 89118

Phone: 702-248-2770

24-hour Helpline: 800-272-3900, operates seven days a week, in 140 languages

Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health

Address: 888 W. Bonneville Ave., Las Vegas, NV 89106

Phone: 702-331-7054

Appointments: 702-483-6000, Option 2

Information about services and programs for caregivers and families: 702-483-6023

Information about enrolling in a clinical trial: 702-685-7073 or brainhealth@ccf.org

Donations: Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Philanthropy Institute, 702-331-7052

Volunteer: 702-331-7046

Keep Memory Alive: 702-263-9797