Radioembolization: Starving tumors to fight cancer

Aug. 17 was the 10th anniversary of 59-year-old Dal Anderson’s carcinoid cancer diagnosis. He commemorated the occasion by writing his cancer a letter. After all, there have been some perks, he says. People say you look good. You find joy most people just brush past. You pick your friends well. You get to tell “the Man” to take a leap sometimes.

Cancer has also been filled with surprises for Anderson. It started with gut pain and a strange copper taste in his mouth. A surgeon cut out 18 inches of his small intestine, then “patted me on the head and said, ‘You’re cured, go live life,’ ” he remembers. Scared to death, he delved more deeply. Others told him that in four or five years he’d have the cancer back, and it would be in his liver.

“They were right,” he says.

In 2008, he lost his job in sales, customer service and training about the time he was undergoing another surgery. He woke up from that surgery to discover that the cancer had spread to his liver — apparently without showing up on a test.

He’s shooting for five or six more years of life, minimum. But prognoses from others don’t mean much to him.

“The surgeon, they said, ‘You’re cured, go out and live,’ ” he points out. “And I found out that was a lie.”

One approach he’s taken to steer the odds in his favor: becoming the first patient in interventional radiologist Dr. Trey Q. Pham’s new y-90 SIR-Spheres program at Centennial Hills Hospital Medical Center, just a few months ago.

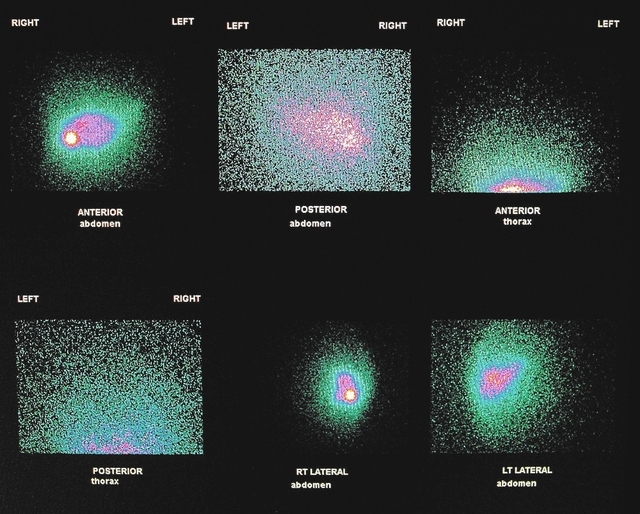

The procedure is radioembolization, also known as selective internal radiation therapy. It targets liver tumors with millions of tiny radioactive beads called SIR-Spheres microspheres, via the tumors’ blood supply. The beads contain the radioactive element yttrium-90, which delivers more highly concentrated radiation to the tumors than conventional external radiation, according to Sirtex, the company that develops oncology treatments using small particle technology, including the microspheres.

“You’re minimizing injury to the healthy tissue and delivering more of the radiation to the tumor itself,” Pham explains.

“I always tell my patients, the worse off they feel, the better off I feel, because I feel like there’s an effect on the tumors,” he adds.

“It’s called radioembolization because after these little beads lodge in the tumor, they then radiate the tumor at the same time,” says Dr. Edward M. Wolin, one of only a few oncologists specializing in neuroendocrine cancer. He directs a large patient care and clinical research program as co-director of the Cedars-Sinai Carcinoid and Neuroendocrine Tumor Program at Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute in Los Angeles.

“So the tumor is deprived of oxygen and food, and in that messed-up state, it is radiated as well,” he says. “There’s a big hit to the tumors that are specifically in the liver.”

Anderson saw Wolin, first, after receiving what turned out to be an incorrect pathology report, which left him with a seeming death sentence. Wolin’s team recommended radioembolization, and, because of insurance limitations, directed Anderson to Pham, who was launching the treatment in Las Vegas.

According to Pham, Anderson’s cancer is only one of many that spread to the liver. Since the research began to heat up on the procedure around 2000, radioembolization has been used to treat primary liver cancer in addition to colorectal and carcinoid cancers that have spread to the liver, he says. There’s also talk of using the procedure to target cancer that’s metastasized to the liver after starting out as breast, lung and esophageal cancer.

Pham emphasized that the procedure is not a cure.

“It’s more of a palliative procedure, where number one, I’m trying to curb the disease process, and number two, trying to give a better quality of life,” he says. For some of his patients, the cancer has stabilized after the procedure. Others must repeat it down the road.

Dr. Richard R.P. Warner, founder and medical director of the Carcinoid Cancer Foundation in White Plains, N.Y., and director of the multidisciplinary Center for Carcinoid and Neuroendocrine Tumors at the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, and another expert on the disease, says: “Somewhere around 80 percent of the cases so treated get an effective, beneficial response. It’s making the tumors regress, smaller, prolonging life. But it will only work on those that are in the liver. The duration of that response varies tremendously, but the average case can expect a benefit to last about two years. However, the treatment can be done over and over again. Some patients, four or even five times.”

But there are other ways to treat tumors in the liver, depending on how many tumors there are, how big they are, and what tumors are outside the liver, Wolin says. For example, chemoembolization, the coating of little beads with chemotherapy to target tumors rather than the whole body. Embolization that uses just plain beads to simply block off the blood supply to the tumor. Putting needles into tumors and microwaving them in a process called radiofrequency ablation, which cooks the tumors inside the liver. Annihilating tumors by injecting alcohol into them. And also, surgery.

Wolin says having so many options is the reason why he has a multidisciplinary team of as many as 20 doctors discussing the ideal management of each patient, every week.

Linda Best, 62, is another one of his patients. She attends the carcinoid cancer support group led by Anderson at The Caring Place in Las Vegas. Best is an avid diver, hiker and bicyclist who says she’s always eaten right. But after years of misdiagnosis of her carcinoid cancer — commonly labeled as everything from menopause to irritable bowel syndrome — the cancer spread to her liver. Wolin placed her on a study treatment, rather than recommending radioembolization, she says. She’s been on it for 14 months, and remains stable.

For those who do undergo radioembolization, Pham hopes to reduce the stress on patients who have traditionally had to travel out of state for treatment.

“It’s a shame to do a procedure where you don’t know what’s going on, you’re not comfortable, and you’re a thousand miles away from your family,” he says.

The procedure itself requires planning. Pham reviews a recent CT scan to assess the extent of the disease. A blood test reveals whether the liver is working well enough to withstand the treatment. There’s also a mapping procedure beforehand, involving an angiogram, done by way of a catheter inserted into the hepatic artery.

Pham uses the catheter to snake his way around. He eventually identifies and blocks vessels so the microspheres don’t travel to areas such as the stomach or small bowel, where radiation could cause ulcers. Each person’s body is unique, he notes, when it comes to the tiny vessels that might allow wayward microspheres to become troublemakers.

He breaks the actual radioembolization into two separate visits: first one liver lobe, and then the other. The goal is to minimize side effects and concentrate radiation on one lobe at a time.

“This actually improves side effects,” he says. “You see multiple people who’ve gone through chemotherapy where they’re losing their hair, or patients who do radiation and a lot of healthy tissues get destroyed. And so with this procedure the side effects are actually much better than the side effects with other chemotherapy drugs or radiation. Most patients are outpatients where they come and do the procedure and then they go home the same day.”

Anderson’s description of the first treatment didn’t resemble a walk in the park.

He lost 16 pounds because he couldn’t eat.

But, “I’m buying myself quality time,” he says.