No easy cure for doctor deficit in Nevada

EDITOR’S NOTE: One in an occasional series on the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Jessica Zarndt is a local gal who made good.

The native Las Vegan earned her medical degree in 2008 from Touro University Nevada College of Osteopathic Medicine in Henderson. She left Las Vegas to complete a residency in family medicine in Texas and moved home to practice in 2011. Today, Zarndt teaches and sees patients at Touro.

"I really love what I do, and I believe in it. I see myself staying in academics and staying here in Las Vegas, and hopefully educating future students," Zarndt said.

There’s just one problem with this success story: Nevada has too few Jessica Zarndts. The Silver State has some of the lowest doctor-to-patient ratios in the nation.

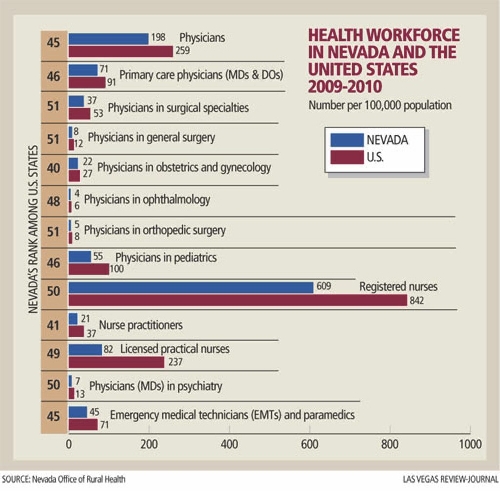

A forthcoming study from John Packham, a health policy researcher at the University of Nevada School of Medicine, ranks the state No. 46 for its share of primary care doctors, family practice specialists and pediatricians. For obstetricians and gynecologists, it’s No. 40. Nevada also ranks 51st in general and orthopedic surgeons, and 50th for psychiatrists.

Physician shortages are so bad the state could double its doctor population in some specialties and still sit at or near the bottom, said Larry Matheis, executive director of the Nevada State Medical Association.

Nevada has limped along for decades with too few doctors, but the situation is about to get critical. As the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act – Obamacare – swells the ranks of the insured, newly covered patients will flock to doctors’ offices. At current staff levels, locals can expect wait times for appointments to skyrocket. Frustrated patients will likely flood emergency rooms for immediate care of colds, sore throats, ear infections and other routine issues – an expensive problem the law was supposed to prevent.

Policymakers and industry experts say they will work on solutions in the 2013 Legislature, which kicks off Monday. But ideas that could make the biggest difference face uphill political battles, or they need funding, a tall order for a state that is already looking under its couch cushions to fund education.

"This is going to be a real test. We are going to see stress on this system unlike anything we’ve seen ever before," Matheis said.

EMERGENCY ROOMS

For a glimpse of how bad things could get in Nevada, consider Massachusetts.

In the two years after that state’s individual insurance mandate took effect in 2006, emergency room visits jumped 9 percent, according to the Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy. ER visits kept increasing through 2012, when they finally began dropping for reasons that are not clear to industry observers.

ER visits rose because when people have coverage, they are more likely to go to the doctor. They may have a chronic illness they can finally afford to treat, or they might schedule a checkup because they have insurance and want to use it. As doctors’ appointment books fill up, more people go where they cannot be turned away – an emergency room.

Nevada could see an even more dramatic shift into ERs, said Dr. Mitchell Forman, dean and professor of medicine at Touro. The state doesn’t have nearly the doctor ratios of Massachusetts, which topped the nation in 2009 for doctors per 100,000 people. Plus, Massachusetts had far fewer uninsured people: Before the individual insurance mandate took effect, 10 percent of its population lacked coverage, compared with 20 percent in Nevada. So not only does Nevada have a far lower share of doctors, it also has more pent-up patient demand.

"Whenever people have difficulty getting an appointment or accessing the system, the emergency department becomes the default place most people go," Matheis said. "Everybody is expecting it. Hospitals are bracing for it."

The problem is, the ER is the worst way to provide non-emergency care. Not only is it the most expensive option, but patients see whoever is on call rather than developing a relationship with a primary care provider who learns their history and stays on top of chronic conditions.

"Having a lot more people with health insurance is just going to confound an already difficult situation here, and probably make it more likely that folks now with insurance are going to go to ERs," Forman said. "They’ll get health care, but it’s not the kind of health care we envisioned with the Affordable Care Act."

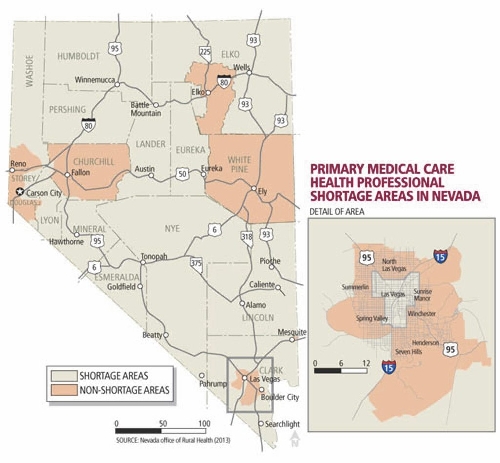

The problem could be especially stark in the city’s urban core, which has an acute shortage of primary care providers because it has far fewer doctors and its population is less healthy and in need of higher levels of care. Doctors set up practice more often in affluent suburban neighborhoods with comparatively healthier populations, Packham said.

Experts say the state does have short-term options to help ease the burden on local medical systems, but some of those choices could see resistance.

EXPANDED NURSING ROLES

Several local industry experts pointed to one quick way to boost the number of primary-care providers: Rewrite state law to expand the scope of practice for nurses and physicians’ assistants. Right now, nurses and PAs practice under doctor supervision; but wait times could drop if some professionals, particularly nurse practitioners with advanced degrees, could independently treat patients who have everyday ailments, such as strep throat or mild seasonal allergies.

The idea has the attention of lawmakers. State Sen. Justin Jones, D-Las Vegas and chairman of the Senate’s Health and Human Services Committee, said nurses and physicians’ assistants "will play a critical role in meeting our increased health care needs," and the committee will look at laws covering their training and scope of practice.

The idea isn’t universally popular, though. Dr. Thomas Schwenk, dean of the University of Nevada School of Medicine, called the role of nurses and PAs "a very controversial issue."

Added Matheis: "There’s a lot of anxiety on the part of doctors about having as much training as they have, and seeing others with less training billing for the same services. But I think, for the most part, doctors agree that people who are well-trained have a lot to add, and we’re not going to get through this without using everybody in the system to their maximum."

Matheis said the question is how do you build public safety into the system and keep down liability costs if patients feel they didn’t get adequate care?

Plus, asking nurses to do more can’t be the sole answer: Nevada also ranks 50th in registered nurses and 49th in licensed practical nurses per 100,000 residents, according to Packham’s School of Medicine study. And that’s after doubling public nurse-education programs in the past decade.

So, lawmakers must also look at immediately boosting doctors’ ranks, perhaps by easing state licensing requirements.

Forman said it took him eight months to obtain his Nevada physician’s license, despite decades of practice in multiple states and an unblemished disciplinary record. By contrast, it took him a month to get licensed in Michigan.

"If someone has board certification and unlimited licensure in another state, with no major difficulties in terms of their practice, that should be enough reason to expedite their application, particularly in a state where we need people so desperately," Forman said.

Doctors have proven before that they are willing to come here.

Nevada’s doctor shortage is more a result of exploding population than a dim view of the state as a place to practice, Packham said. Its number of family medicine practitioners jumped nearly 210 percent from 1990 to 2010. Its number of specialists spiked 233 percent.

"In terms of setting up a practice and having plenty of patients to see, Nevada in general, and Las Vegas in particular, were pretty attractive until the recession of 2007," Packham said. "You had 5,000 people a month moving here, and 80 to 85 percent of them had insurance coverage. That’s a lot of paying clients."

So many that it overwhelmed the system: Southern Nevada’s population alone doubled from about 1 million in 2000 to roughly 2 million in 2012. Doctor growth just couldn’t keep up.

That’s not to say the state has an otherwise perfect recruiting pitch. A lot of doctors don’t consider Nevada "a serious medical marketplace," Schwenk said.

The state has no dominant health system or major medical school. Care is disjointed, spread among thousands of small practices, clinics and hospital systems. That makes it hard for some doctors to see where they would fit in, or how they would get a practice going. Nor does the state’s fragmented system offer the fellowships and referral networks of other markets.

Still, the market does have appeal. Just ask new doctors and medical students.

Zarndt returned to Las Vegas because she is from here, but she is convinced more doctors would come if they could see life away from the Strip, including outdoor activities, churches and other community draws. Creating larger practices would help, too, because they can pay more than smaller offices, she said. And don’t discount the lure of opportunity.

Opportunity is partly why second-year Touro student Kristina Buscaino left suburban Los Angeles for Henderson. Buscaino said she is not sure what type of medicine she will practice, but she is pretty certain she wants to practice it here.

"There are a lot of hospitals, and a lot of patients who need care here," she said. "With health care reform, there’ll be a need for new doctors."

Nevada can’t fill its need for doctors from the outside alone. The long-term solution is to grow more physicians here through residencies. Right now, Nevada has the smallest number of residencies of any state, Matheis said, and that’s a problem because the vast majority of doctors practice within 50 miles of where they train.

If little training is available here, then the state will continue to produce too few doctors.

ATTRACTING MORE DOCTORS

The University of Nevada School of Medicine has about 275 residents, though that is going up to 325 in the next couple of years. Touro has 82 residents. Neither institution says that’s enough.

"We’re so far behind, it’s almost hard to imagine," Schwenk said.

The University of Nevada would need 30 to 50 more primary-care residencies a year for the next three years to begin making a dent in need, Schwenk said. Its faculty of 200 should be at least three times that size to churn out enough local doctors. At Touro, Forman said doubling residents would help considerably.

But there’s little hope of new funding for such big strides. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services finances the bulk of graduate medical education, including resident stipends and faculty salaries. The agency is more likely to cut spending than boost it, Forman said. That makes hospitals nervous about committing to large numbers of new resident spots.

If the federal government won’t fund graduate medical education, industry experts said they would like the state to step in with money. But with K-12 education and colleges and universities already consuming 55 percent of the state’s two-year, $6.2 billion budget, and little promise of added revenue for more education spending, it will be hard for the state to help much, Forman acknowledged.

Still, legislators should look at how they allot Medicare and Medicaid funding. For example, some spending could shift from expensive, unnecessary treatment into residencies, particularly in high-need specialties.

The Legislature could also offer hospitals tax breaks to add residents or improve malpractice protection, Forman said.

Nor should residencies happen through hospitals alone. Outpatient clinics and primary-care practices should get training dollars to increase opportunities to train more doctors in basic care, Packham said. The state could even reimburse primary-care residents .

To attract more doctors, Southern Nevada also needs an academic health science center, a partnership between a university and private health providers focused on breakthrough research that can help patients today. Such centers "raise the bar of quality" and draw doctors, Forman said, but it has been difficult to create one here because most hospitals are focused on their own state-of-the-art services, rather than collaborating.

"We have unbelievably duplicative services that are very inefficient, mostly because of issues of ownership," Forman said. "Everyone wants to own it. No one wants to do this as a partnership. We have not been able to get private and public to work together."

For now, public and public are working together, at least. The University of Nevada School of Medicine and the Clark County-owned University Medical Center have partnered on trauma care for more than 20 years, and they are working together to build a program in cancer research and care.

The necessary improvements could take years to happen, but that doesn’t lessen the importance of launching them now, Matheis said.

"We understand we can’t double the number of residents in two years, but we’ve got to be moving in the right direction," he said. "We can’t just sit and wait and hope. The answers aren’t going to get any easier."

Contact reporter Jennifer Robison at jrobison@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4512. Follow @J_Robison1 on Twitter.