Nevada ranked last in public health disaster readiness

Another piece of Nevada’s health care system – its ability to respond to a public health crisis — is drawing unwelcome attention.

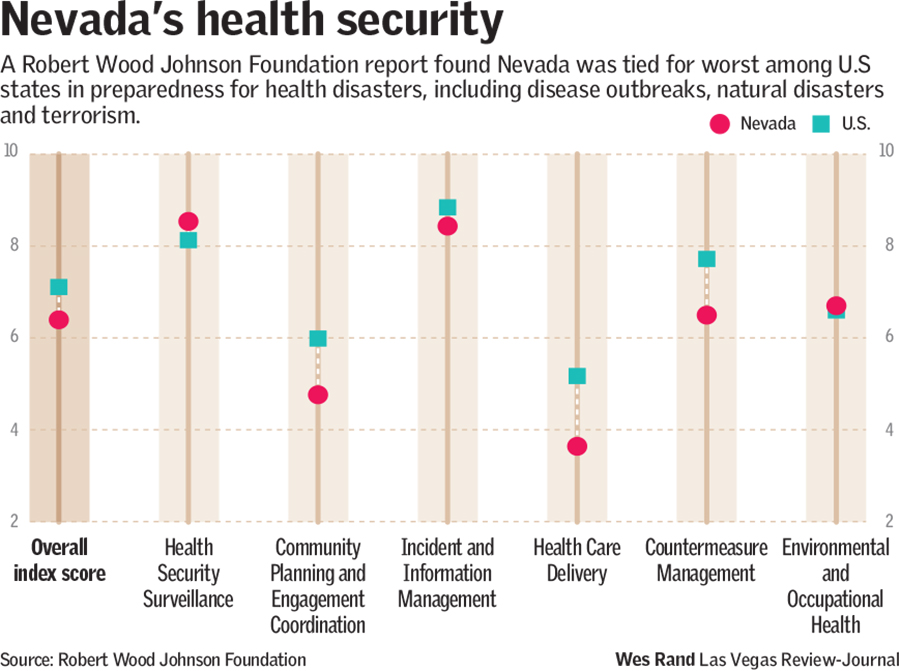

A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation report released late Monday found Nevada was tied for worst among U.S. states in preparedness for health disasters, including disease outbreaks, natural disasters and terrorism.

The state’s biggest issue: delivering care — particularly mental heath care — during and after a disaster like the Oct. 1 shooting, which killed 58 and wounded hundreds more.

Glen Mays, director of the foundation’s National Health Security Preparedness Index program, said that’s largely because there aren’t enough health professionals in Nevada to handle the growing population, causing its health care delivery index score to fall 7.5 percent from 2016 to 2017.

The state’s overall score of 6.4 tied it with Alaska for worst in the nation. The score is calculated on 140 measures grouped into six categories and 19 subcategories. Nevada scored above the national average in health security surveillance and in the subcategories of food and water security and biological monitoring and laboratory testing.

Still, Nevada’s score is falling when it comes to providing care, especially in mental health, which saw the largest decline — 55.3 percent — from 2016.

It’s a concerning trend, Mays said, and to some extent, it’s happening across the country.

“There are a lot of demands on our health care system for everyday health care needs, and we’ve had a lot of change in our health care system of the last five or six years,” Mays said.

He was referring to expanded health care coverage under Medicaid, which has granted more than 200,000 previously uninsured Nevadans access to care. But the availability of trained professionals and health systems hasn’t kept up with the growing insured population, Mays said, creating a shortage of health workers and services that will take time and money to erase.

According to the report, the state was designated a mental health professional shortage area in 2017 by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration for the first time since the foundation launched its index scoring system in 2013.

The growing demand is at least partly attributable to the Oct. 1 shooting, said Catherine O’Mara, executive director of the Nevada State Medical Association.

“I do know that it takes a long time to heal from that kind of trauma and to move forward, so I do have concerns that we don’t have enough providers,” O’Mara said.

Investing in the future

Apart from hiring more health professionals statewide, Mays said Nevada could improve its disaster readiness by bolstering communications among emergency medical services, hospitals and nursing homes.

“That’s a relatively low-cost thing that state and communities can do.”

The state’s Division of Public and Behavioral Health has implemented incentive programs, including the National Health Service Corps, the Nurse Corps and the Nevada Health Service Corps, to mitigate the provider shortage, spokeswoman Martha Framsted said in an email Tuesday.

And the inaugural class of UNLV’s medical school is on its way to completing its first year of instruction.

“I think continuing to invest in medical education, northern and southern, and developing residency programs are both really important for investing in and tracking new opportunities here,” O’Mara said.

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.