National, local efforts take aim at epidemic of obesity in children

No doubt about it, America’s kids are fat. They’re so fat that first lady Michelle Obama has launched a multipronged initiative to bring attention to the situation and its inherent health risks, and to work toward a remedy.

In Southern Nevada, the problem of childhood obesity is even more serious, because our kids are even fatter than their counterparts across the country.

Doctors with the Nevada State Health Division said during a hearing May 26 that 22 percent of school-age children in Clark County are obese, compared to 17 percent nationwide.

"I think a lot of the problem is that you have a lot of shift workers here in Las Vegas, and quick access to lower-cost buffets and food items, around-the-clock access to food and alcohol," said Robin Morello, a bariatric nurse with the University Weight Loss Center, a partnership of University Medical Center and the University of Nevada School of Medicine.

Angelique Martinez, a registered dietitian with the Children’s Heart Center of Sunrise Children’s Hospital, said because most Las Vegas families either have both parents working or a single parent who works, "the options for food are something quick, because Mom or Dad’s tired, and they don’t have a lot of money or time to spend making healthier meals. The availability of so much fast, easy, convenient, sugary, fatty foods makes it hard."

Add a tendency toward sedentary behavior and a lack of natural sources of exercise — such as walking to the grocery store — and the result is an obesity problem. And when a family’s lifestyle habits are poor, it affects everyone.

"There does seem to be a halo effect, where children of obese parents tend to be obese," said Dr. Shawn Tsuda, an obesity specialist with the University Weight Loss Center. "And in turn, obese children have a 60 percent to 70 percent chance of being obese adults."

Obese children face increased health risks such as Type 2 diabetes, which in the past primarily affected adults.

Solutions to the problem are elusive, but one place people are looking for answers is the schools.

The Clark County School District has a wellness policy that addresses such issues as goals for nutrition and activity, with provisions for measurement and accountability.

At school, kids are getting healthful foods — or at least it would appear.

Virginia Beck, registered dietitian for the school district’s food service department, said schools provide nutritious, low-fat, low-cholesterol, low-sodium meals with no trans fats and with the amount of calories and nutrients recommended by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for each particular age group.

Even when high school students are served pizza or burgers as part of their school lunch, the items contain less than 30 percent fat and meet other nutritional guidelines, Beck said. But she added that there is only so much her department can do.

"It’s difficult," Beck said, "because I don’t really have any control over what the schools do."

Terri Janison, president of the Clark County School Board and a member of the district’s new wellness committee, said, "There are schools that don’t follow the wellness policy, so that’s been somewhat of a frustration, and I’ve been very vocal about it."

Janison said the wellness policy "addresses, literally, parties and things," in an effort to keep schools from circumventing food services.

But why would they?

"Because I think it’s what people choose to do in their own personal lives," Janison said. "If they don’t choose to adhere to those rules for themselves personally, they might not think it’s important for the students."

Economics is another complication.

Neighborhoods with a high proportion of lower-income residents tend to have a correspondingly higher number of fast-food restaurants and convenience stores, said Monica Lounsbery, director of the physical activity and policy research program at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

And healthful foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables either seem to be or are out of reach.

"Fresh fruits and vegetables are much more expensive," Janison said.

She remembers a case when children at a school in a lower-economic area were given fresh apples in the lunchroom.

"They looked at it and didn’t know how to eat it, so they tried to peel it with their teeth," she recalled.

The school district has received an assist from the Chefs for Kids organization, which has worked for years to provide hot meals to children at 12 local at-risk schools and teach good eating habits and nutrition.

Christopher Johns, executive chef at South Point and chairman of Chefs for Kids, was one of more than 500 chefs who attended Obama’s "Chefs Move to Schools" kickoff event June 4 at the White House.

"This new thing for Mrs. Obama is more for individual chefs in different cities to get involved and to adopt a school and to go in and start talking to the children and teach a very few basic cooking skills," Johns said, "what you can do with nutritious food and how simple it is to prepare a meal compared to going through the drive-through or microwaving Doritos from the convenience store. Broccoli can be very nice if it’s cooked properly, but if it’s stewed or not cooked enough, it’s not good."

Tsuda said he thinks schools should be doing more on both the dietary and fitness fronts.

"We do know the things that contribute to obesity in Las Vegas, with things like sedentary lifestyle and not having enough state or city initiatives to battle obesity, especially in young people," Tsuda said.

"There should be things to promote better diets in schools, and more information for young people as early as grade school or middle school on avoiding unhealthy fast foods and things of that sort, and exercise more. There’s more and more of these things going on out there, but there needs to be more of a push on the state level and the city level."

That’s difficult for schools during recessionary times when cuts are the norm.

"The challenge is that schools have a lot more to do," especially when they’re trying to meet the mandates of No Child Left Behind and similar initiatives, Lounsbery said.

"As we cut things in education, a lot of times the first things to go are physical education, exercise programs and things like that," Morello noted.

And she gets no argument from Janison. As far as physical education, she said, students in the district get "not enough — period."

"The reality is the minutes of the day that we are provided are what we have to offer these children academically," Janison added.

Another challenge is that families are not getting physical activity at home. Janison said she is somewhat puzzled because she sees packed soccer, football and Little League fields. But Lounsbery said the reality is that only 20 percent of Americans meet guidelines for physical activity.

In Las Vegas, she said, the environment itself has much to do with that. Consider our urban sprawl.

"If you walk anywhere in Southern Nevada, you know the sidewalk does end," Lounsbery said. "There are no more neighborhood markets."

Changing times are a contributing factor as well.

"Before, when people went to work, they expended calories," Lounsbery said. "At every age level, people are sitting more and more."

There are no state mandates for how much physical education a student must get, except for the two credits required in high school.

The Clark County School District has its own guidelines, however.

Diana Cockrell, who is principal at Hollingsworth Elementary School, said elementary students in the county are to get two 50-minute physical education periods a week. Of that, she estimates that 30 minutes of each period are active time, with the balance instructional.

The district caps PE class sizes at 75, Cockrell said.

Lounsbery noted a survey of 155 schools across the country found average physical education class sizes of 33.

"And they have recess (which is 15 minutes) every day," Cockrell said.

Hayden Ross, who until recently was a district physical education facilitator, said agencies including the federal Centers for Disease Control and organizations including the National Association for Sport and Physical Education recommend 150 minutes of activity per week for elementary students and 225 minutes for students in middle and high schools.

"Not just physical education," Ross said, "but in addition physical activity could be a walking club before school or any number of things in school, or after-school activities that are open to everyone."

"We know that kids need some unstructured playtime," Cockrell said. "Even as an adult, it’s hard to sit in a chair all day long."

And that may be the key to solving or at least fighting the problem: keeping kids moving.

"The wellness committee is trying to incorporate into professional development how to incorporate movement into your teaching," Janison said.

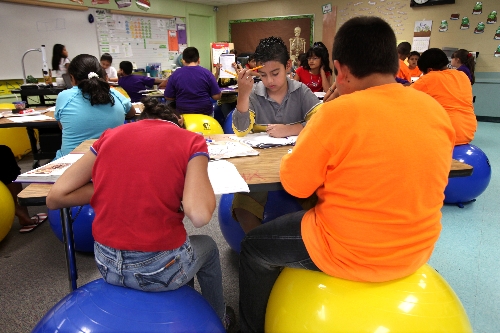

At C.P. Squires Elementary School, one of 14 local schools to benefit from a $1.3 million federal grant over the next three years, movement is part of the routine.

Marcie McDonald, who has been principal at the school for six years, has students in four classrooms sitting on fitness balls instead of desk chairs, because the constant, almost unconscious balancing required helps build core strength.

Kids might learn 90-degree angles in math class by getting out of their chairs and stepping through the angle formation. Or, to learn the word "burrow," they might be asked to burrow under their desks.

PE teacher Jerrad Clancy — "He’s pretty awesome," McDonald said — teaches dance at recess.

The school population is 92 percent Hispanic, so Clancy has taught things such as Mexican folkloric dance. But a recent acquisition is a Miley Cyrus tape so the kids can learn the dance in the "Hannah Montana" movie.

Clancy also started an after-school intramural soccer program, students learned to swim at a nearby pool and the school has a walking program for students and their families, with logs kept and prizes awarded for miles walked.

"Our kids don’t stand around," McDonald said.

Ross said such innovative programs are a key to reducing obesity, and cites a move away from a sport-based PE curriculum, which can alienate the less athletically gifted. Thanks to the grant, Ross said, some schools have received fitness-center equipment and other nontraditional sports equipment such as yoga mats, scooters and tricycles.

"We’re really trying to engage kids in activities that they already are naturally inclined to participate in," she said.

A goal is to keep kids moderately physically active for at least 50 percent of class time. And family nights demonstrate to parents how many cubes of sugar are in a Gatorade and let them try out the fitness equipment "and have fun with their kids."

Because it’s really about more than having fun.

"Using projections to see how much is spent on unhealthy living, there will never be enough money to address half of the care that will be needed," Lounsbery said.

"The pattern needs to be changed, because of the implications for learning — and for what we aspire to be as a nation."

Contact reporter Heidi Knapp Rinella at hrinella@review journal.com or 702-383-0474.

VIDEO: Combating obesityBY THE NUMBERS

22% — Percentage of school-age children in Clark County who are obese, compared to 17 percent nationwide.

60%-70% — Chance that obese children will be obese adults.

20% — Percentage of Americans who meet guidelines for physical activity.