Nancy Nelson answers Alzheimer’s diagnosis with poetry writing

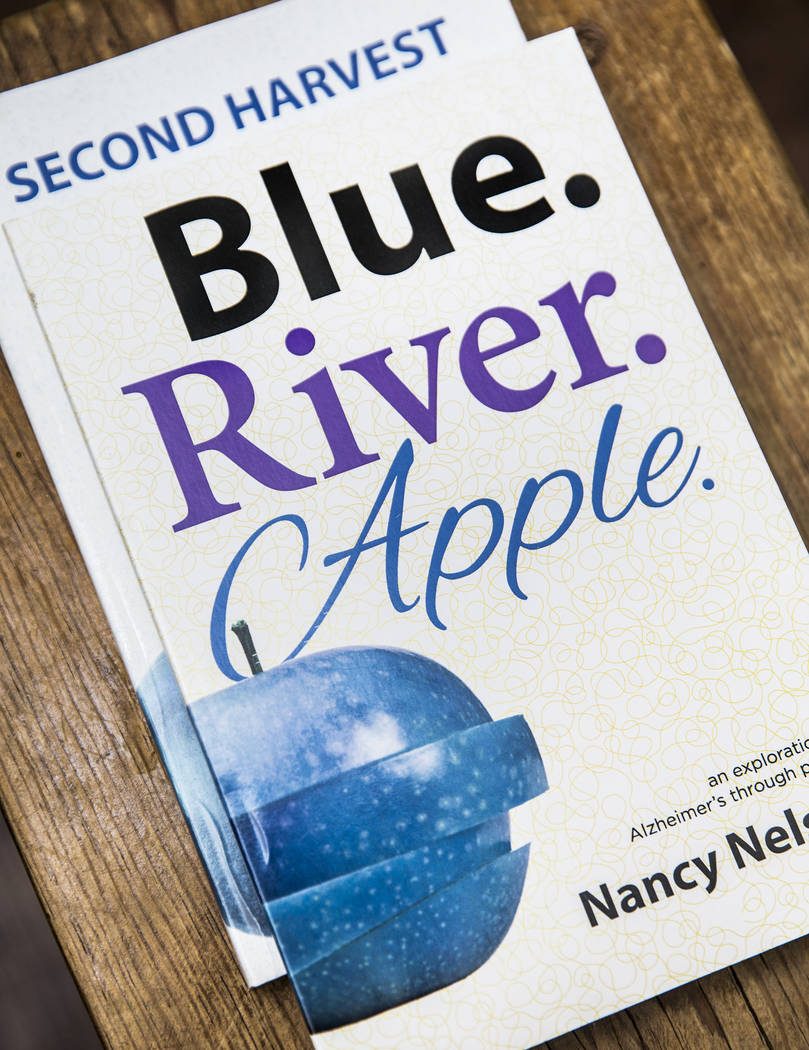

Blue, river, apple. It’s a disjointed series of innocuous words that sent Nancy Nelson on a journey she hadn’t prepared for and never wanted to take.

The words revealed that Nelson suffers from what then was diagnosed as early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Since then, the words have come to symbolize Nelson’s fight against what is going on in her brain, as well as the title of two books of poetry in which Nelson examines, with open eyes, deep feeling and wry humor, the trials, fears and everyday realities of living with Alzheimer’s.

Nelson, now 74, began to notice during her mid-60s that she was becoming forgetful. Despite having lived in Las Vegas for 50 years, she couldn’t link together the streets that would take her from here to there. She’d meet someone and forget the next day that she did. She blanked out on social appointments, resorting to fibs to cover up her memory lapses.

Blue, river, apple

Finally, in September 2013, at age 69, Nelson saw a doctor for an assessment. At the beginning of the exam, she was given three words — blue, river and apple — to remember. After a few more tests, she was asked to recall the three words and could remember just one.

Nelson laughs. “I’ll never forget blue, river, apple, thank you for asking,” she jokes.

Nelson’s father died in 2002 of complications from Alzheimer’s. But Nelson always had been well. She ate healthily, kept active, and her careers, first in the airline industry and then in insurance, were mentally stimulating.

“I found the diagnosis not to be believable, actually,” Nelson says. “I never worried about getting Alzheimer’s disease, even though my dad passed with Alzheimer’s. I never saw me having it. And when the words were said to me, I was shocked. I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t digest the severity of it.”

Nelson’s youngest daughter, Jennifer, was there to hear the doctor’s words with her.

“Jennifer and I sat there after he said it,” Nelson says. “He tried to hand me a prescription. I said, ‘Too soon. Too early.’ He left. Jennifer and I just looked at each other. We walked out in a daze, leaving the office.

“We got into the car and we hugged one another and we cried. Jennifer and I looked at one another, thinking, ‘Wow.’ It was a quiet ride home. I didn’t know what to say. I had brought her here thinking they were going to say ‘No.’ ”

Plotting a course

Nelson began to research Alzheimer’s disease and decided to share the diagnosis with her children and grandchildren.

“I have two girls and four grandchildren, and I’m ever-present in their lives,” Nelson says. “I decided when I got the diagnosis that I was going to bring everyone along with me.”

They’ve been supportive, and she hasn’t been shy about sharing her story with others, too. She notes that cancer once carried the stigma Alzheimer’s now does, and that “not so very long ago, the way to handle it was to keep family away. Fifty years ago it was the Big C. Now it’s the Big A.”

What eliminated cancer’s stigma was “people talking,” Nelson says. “So what I decided to do for myself is, I’m going to take this melted ice cream cone and I’m going to go back (and) get another that’s solid and good, and I’m going to start talking about it and help people.”

“And I’m so ordinary,” Nelson says, smiling. “I’m so average, ordinary, next-door-neighborish that they listen.”

The words flow

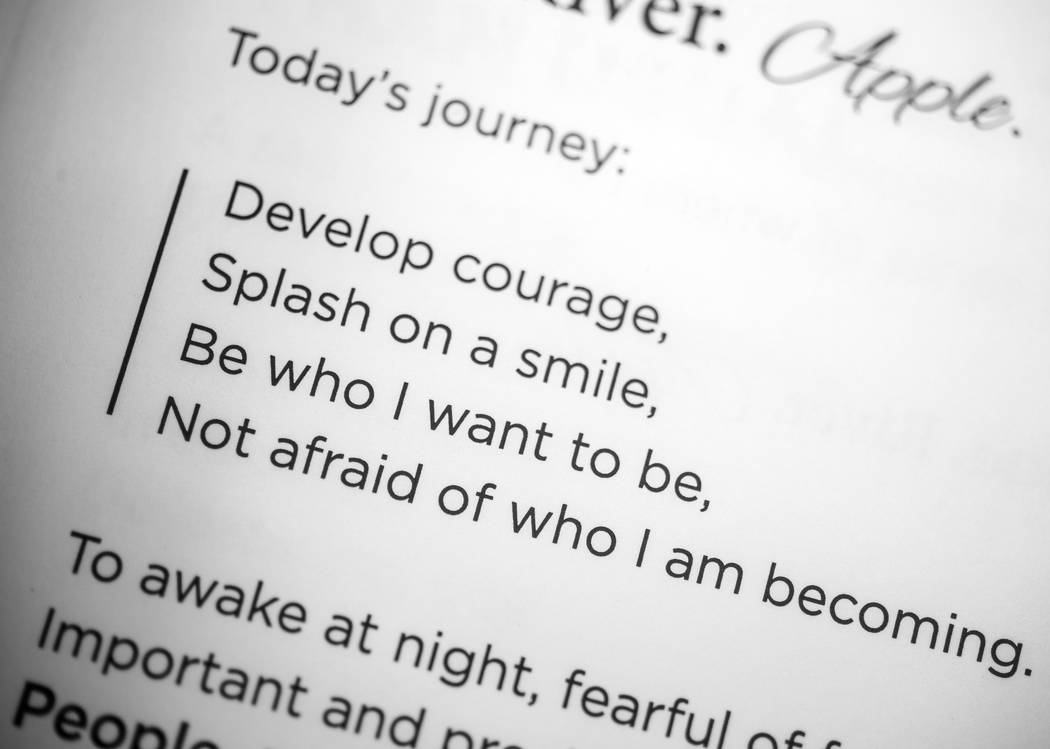

Nelson never had written poetry. But, she says, “the poems came to me immediately. Within days of getting the diagnosis, I would wake up between 3 and 5 a.m. in the morning and write. I told a friend, ‘I don’t know what’s happening to me.’ ”

However — or, Nelson says, from whomever — they came, Nelson found writing poetry to be therapeutic, helping her to work through her feelings.

“The poetry was journaling for me,” she says. “I was mad at doctors. I was frustrated at not remembering. I was perplexed when I couldn’t get from here to across town (and) connect the streets where I wanted to go.”

She considers her poetry “profound in a way. It’s short, it’s succinct. There’s a message in all of them. There’s hope that things are going to get better, and I feel (that more) today than I did back then. Things are going to be OK.”

Lifestyle changes

Nelson, now retired, also made changes in her lifestyle. She now follows a mostly vegan, Mediterranean diet. “Plant-based is really where it’s at.” She starts each day with 30 minutes of stretching, walks or runs several miles each day, does breathing and stress management exercises and challenges her brain with mental exercises and counting.

“I’m fighting to remain who I am in an ever-changing battle to do that,” Nelson says.

Nelson and her granddaughter also are writing a book that will explain Alzheimer’s to children using a penguin character, while her next book will be directed toward caregivers.

A new diagnosis

Nelson says a more recent medical assessment resulted in a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, in contrast to that initial diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

The new words don’t mean much to her, though. “I didn’t own the first diagnosis and I’m not owning this diagnosis, either, because nothing has changed for me,” she says. “I do the same silly things.”

Nelson finishes her story, takes a breath and smiles. “So I don’t know. Here we are. I will say to you, there is hope.

“Some people will say to me, ‘You’re in denial.’ Some people say, ‘That’s crazy.’ Other people say, ‘You don’t have anything wrong with you.’ ”

She laughs. “I say, thank you. I don’t know. I mean, I didn’t ask for this. I’m just going by the seat of my pants, doing the very best that I know how, and I really think that’s what everybody should do.”

The right things

Dr. Dylan Wint says positive lifestyle changes are “pretty significant” in helping to slow the progression of mild cognitive impairment.

Wint is a neurologist and researcher at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health. He’s also Nancy Nelson’s neurologist, and (with Nelson’s permission) describes her current diagnosis as “mild cognitive impairment, probably due to Alzheimer’s disease.”

However, Wint adds that, by following such lifestyle practices as getting regular exercise and watching what she eats, Nelson is doing all the right things.

For example, Wint says, it’s recommended that “people get about 150 minutes of aerobic exercise each week at a moderate level. What I tell my patients is: Enough that you get somewhat short of breath, but not so much that you can’t hold a conversation.”

Aerobic exercise may help to stem the progression of cognitive impairment in several ways, including by improving blood flow to the brain, Wint says. Exercise also can help to manage such conditions as hypertension and diabetes — both of which are risk factors for dementia — as well as depression, which also is a risk factor.

Nelson’s change to a largely vegan, Mediterranean diet — which is heavy on vegetables and plant-based foods and sparse on red meat — also is beneficial for brain health, Wint says, noting that “probably the strongest evidence we have for dietary intervention to improve brain health” is a combination of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets.

Lifestyle changes can have the greatest impact on brain health during earlier stages of disease when, for example, memory problems are just beginning to appear, Wint says, so “it’s really important for people to know that if you do have some memory (issues), that they still have options in their day-to-day life.”

Brain health tips

The Cleveland Clinic’s Healthy Brains website, healthybrains.org, offers visitors a free brain checkup, individualized information about potential health risks and information about lifestyle habits that can help to protect the brain.

The site also offers information about the Cleveland Clinic’s “Six Pillars of Brain Health”:

■ Physical exercise

■ Food and nutrition

■ Controlling medical risks

■ Getting enough sleep and managing stress

■ Mentally exercising the brain

■ Social interaction and staying connected to others

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280. Follow @JJPrzybyson Twitter.