Las Vegas sisters share the gift of life through transplant

It was a miracle, the sisters remember, that the doctors seemed to make so routine.

On March 7, 2011, during medical procedures at University Medical Center, a kidney was removed from Darlene Graham and then transplanted into her sister Sharon Zink.

"The whole thing went just the way they said it would," the 69-year-old Sharon, a retired hairdresser, recalled on a recent Saturday morning as she sat on the couch in her 56-year-old sister’s Henderson home. "We had a fantastic transplant team, just awesome. It’s a miracle to me that a kidney can be taken from one person to save another’s life and both end up feeling great."

Darlene, a legal assistant, nodded in agreement and teared up.

"It’s an experience I will never forget and always cherish," she said. "I saved my sister’s life. To be able to do that, to know that she will live on, it has touched my heart so deeply."

Last week the sisters were part of a symposium at UMC designed to educate social workers and health care professionals about the transplantation process. Karen Hess, the director of transplant services, said the goal was to expand access to kidney transplants as a treatment option.

The all-day conference dealt with issues that included how patients are referred for transplant, selection and evaluation of patients, and living-donor transplants.

"I also want prospective patients and living donors to know that there’s no need to go out of state for a transplant," Darlene said. "We have one of the best programs right here. I’m telling you the doctors make miracles routine."

SMOOTH OPERATION IN LAS VEGAS

That miracles are referred to as routine in the kidney transplant process in Las Vegas – statistics show the local program functioning at better than the nationally expected rate – is a long way from how it was referred to just four years ago.

Back then there were two struggling, underfunded and understaffed programs, one at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center and one at UMC. On July 1, 2008, Sunrise officials announced they would merge their program into UMC’s.

Then in September 2008, UMC’s program was shut down because of illness to its lone transplant surgeon.

About 60 days later, and just four months after becoming the state’s only kidney transplant program, UMC was stripped of that privilege because of quality deficiencies, leaving in doubt what 200 Nevadans awaiting kidney transplants would do.

Documenting 45 deficiencies, including five deaths within a year of transplant, more than double the expected rate, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS, notified UMC that its certification for transplant would be revoked.

The state’s congressional delegation – Reps. Shelley Berkley, Jon Porter and Dean Heller and Sens. Harry Reid and John Ensign – worked to get the decertification stayed, arguing that the suicide of one patient had thrown the statistics out of whack and that other deficiencies were administrative and easily correctable.

Also persuasive to federal officials was the promise of a new $1 million commitment by UMC to the transplant program, which included the hiring of new administrative staff and a temporary contract with highly regarded transplant surgeons, including two from the renowned University of Utah transplant program.

IMPROVING AMID CONTROVERSY

Though the successful efforts to block the federal bid to close the kidney transplant center have been lauded for enabling Nevadans with kidney disease to have lifesaving transplants close to home, The New York Times raised questions last year about the propriety of Berkley advocating for a kidney program at UMC in which her husband, Dr. Larry Lehrner, has a financial interest.

The U.S. House of Representatives announced this month that it will formally investigate Berkley over allegations that she violated House rules by using her position in Congress to benefit her husband’s medical practice, which includes a partnership in Kidney Specialists of Nevada, a group contracted with UMC for about $700,000 a year to deliver a full range of kidney care, including transplant evaluation.

Berkley, locked in a tight race for the Senate seat now held by Heller, has also introduced bills to benefit kidney doctors and fought lowering Medicare reimbursement rates for doctors who do dialysis. In a partnership, Lehrner operates a number of dialysis centers in Las Vegas.

Amid the controversy, the UMC transplant center quietly continues to make strides in its quality of care.

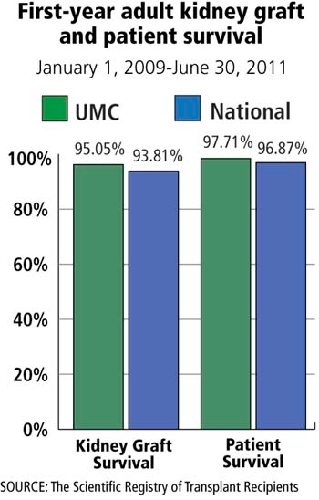

Earlier this month, the center received word from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients that during the reporting period between January 2009 and June 2011, one-year patient survival at UMC was 97.71 percent – there were two deaths out of 98 transplants – compared with an expected national rate of 96.8 percent.

Since July 2011, the UMC transplant team has done 91 more transplants with no deaths. There are now 84 people on the hospital’s transplant list.

UMC’s kidney survival rate from 2009 to 2011 – if a transplanted kidney fails the recipient can go back on dialysis – was 95.05 percent, compared with the national expected rate of 93.81 percent.

Since 2010, UMC’s transplant team has been permanently headed by Hess on the administrative side and Dr. John Ham, formerly of the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, Ore., on the clinical side. Ham also brought on board Dr. Jordana Gaumond and Dr. Bejon Maneckshana. Among the three surgeons, they’re closing in on 2,000 transplants in their careers.

Special nurses, pharmacists and social workers were also hired.

"We’re now capable of doing 100 transplants a year," Ham said. That’s more than double the number currently done.

According to the United Network for Organ Sharing, about 90,000 Americans are waiting for kidneys, but fewer than 17,000 receive one each year. About 4,500 die waiting.

Sharon and Darlene, along with their husbands, hope more Nevadans will consider being living donors – such transplants save taxpayers’ pocketbooks as well as lives.

TRANSPLANTS SAVE MEDICARE MONEY

Medicare, which covers most treatment costs for severe kidney disease, saves money each time a live donor transplant removes an individual from dialysis, according to the National Kidney Foundation. Though a transplant costs more than $100,000, just one year of dialysis costs $70,000. Even with Medicare spending an average of $17,000 a year for the immunosuppressive drugs for a kidney transplant recipient, health experts say the health program saves more than $500,000 each time a patient is removed from dialysis.

Initially, when Sharon thought about a transplant – her kidneys had been failing for five years and she was about to go on dialysis at the time of her procedure – she did so in terms of receiving an organ from a cadaver.

"I didn’t want to put my family or anybody else at risk," she said. "Only when I became educated did it make sense to me."

In what is seen as an aberration in human development, people have two kidneys when they only need one to filter waste and remove excess fluid from the body. Even stranger, if one fails, the other one generally does, too.

"My tests today show that I’m doing just as good or better with one kidney," Darlene said.

Although transplant surgeons note that the vast majority of people can live normal, healthy lives with just one kidney, a living-donor transplant is not without risk. As many as 2 percent of donors suffer complications, according to the National Kidney Foundation, with 50 percent of those needing a follow-up corrective procedure. The federal government has estimated the chance of donor death at 0.03 percent, or three in 1,000.

THE BEST OPTION FOR KIDNEY TRANSPLANT

Largely because donors can be tested thoroughly before transplantation, a living-donor kidney is the best option for a kidney recipient. Half of living- donor kidneys transplanted today will still be functioning in 25 years; half of cadaveric kidneys will fail in the first 10 years. Yet only a third of transplants nationally are from living donors.

Despite her sister’s protests, Darlene decided she wanted to donate a kidney to her sister. She prayed that she would be immunologically compatible. She doubted Sharon could handle dialysis long. It’s a four-hour, three-times-a-week process that leaves many so exhausted that they can’t work or even handle day-to-day travel or chores. Just half of dialysis patients survive more than three years.

At first, Graham felt comfortable only about donating an organ to a family member. But the more she looked into what being a living donor could mean, she decided donating to a stranger could still help her sister.

She researched what are known as paired exchanges, a technique of matching willing living donors to compatible recipients. For example, if Darlene couldn’t donate to her sister because she wasn’t a biological match, she could donate her kidney to a matching recipient who also has an incompatible but willing partner. The second donor, of course, must match the first recipient to complete the pair exchange.

A paired exchange is the simplest case of a much larger exchange registry program. In February, the final link in a domino chain of 30 kidney transplants took place across the country as donors gave a kidney to a stranger after they learned they could not donate to a loved one. In turn, their loved ones received compatible kidneys in exchange.

As it turned out, Darlene needn’t have been concerned over compatibility. She was a perfect match.

On the day of the transplant, before Darlene was wheeled back to have her kidney removed, she heard Sharon call out: "You can still back out if you want to."

"No way," Darlene said.

It took Gaumond less than three hours to remove her kidney. And it also took Ham less than three hours to attach it inside Sharon’s abdomen – largely because of possible surgical complications, nonworking kidneys are left in transplant recipients.

Immediately, the new organ began to work, producing urine.

Four days later, Darlene left the hospital. The next day her sister did.

Neither woman complained of pain, only fatigue. A month after her procedure, Darlene was back at work.

"I felt better right way, better than I had in a long, long time," said Sharon, who must take six anti-rejection pills per day. "It just took me a few months to get back all the energy that I hadn’t had in years."

How did Ham, UMC’s chief of transplantation, view what the sisters say was a lifesaving miracle?

"It went well," he said, matter-of-factly. "Just routine."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.