Las Vegas hospital raises awareness about Medicaid repayments

A video of a swaddled baby, hooked up to breathing tubes, his tiny fingers and toes poking out from underneath a wrap, leads the homepage of the Every Baby Counts Nevada campaign site.

A young mother, Brooklynn, speaks to the camera and relates how one of her two premature twins, Rose, died at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, despite receiving the best available care for newborns in Southern Nevada, while her son, Johnny, survived heart and kidney issues.

“Without all the advanced technology that they have, I mean, they wouldn’t have made it at all,” she says, speaking through tears.

Her story is part of the hospital’s campaign, launched in November, to raise awareness for what it says are unsustainable reimbursements from Nevada Medicaid that threaten its ability to provide the costly services associated with high-level infant care.

“Nevada’s sickest babies need your help,” the video’s headline reads.

$77M in uncompensated care

Babies requiring care in the neonatal intensive care unit, or NICU, can cost the hospital thousands of dollars daily, depending on the equipment or medication required to keep them stable, said Sunrise CEO Todd Sklamberg.

But Medicaid, the insurer for about 70 percent of the hospital’s NICU patients, only pays up to $1,487 daily per baby.

The discrepancy left Sunrise Hospital with $77 million in uncompensated costs for intensive infant care last year, Sklamberg said.

Without a bump in payments for the hospital with the most pediatric acute care beds in the state and the only dedicated pediatric cardiology unit in Nevada, Sklamberg said he worries some of the hospital’s highest cost services — he wouldn’t specify which — will disappear.

“There has to be a fair level of reimbursement,” he said. “Right now, it is unsustainable.”

He added: “Given the disproportionate level of acuity here, the need for us is immediate.”

State pays daily rate

Nevada’s Medicaid program is one of just a few nationwide to pay on a per diem rate.

Most states reimburse hospitals based on what’s called a diagnosis-related group — a code that ties a reimbursement rate to the level and type of services provided by the hospital. But Nevada uses a flat dollar amount of $1,487 to pay back high-level NICUs, no matter the level of care provided.

That amount, which results in reimbursement to hospitals on average of about 57 percent of NICU costs, the Nevada Hospital Association estimates, was last adjusted in 2008, according to Nevada Medicaid data. That adjustment cut the $1,960 per diem rate the state used to pay its high-level NICUs by 24 percent.

But Jared Davies, chief of rates analysis and development for the state Department of Health Care Financing and Policy, which oversees the state program, said Medicaid reimbursement rates are usually lower than what private insurers pay.

“Typically, Medicaid rates don’t come anywhere near to matching the costs incurred by hospitals in that setting,” he said.

And Marta Jensen, former state Medicaid administrator, acknowledged that the agency generally doesn’t have the necessary budget to raise rates or to match the rising costs of health care.

To see the impact this can have on a hospital’s operations, consider the case of Roman Macias, who has a congenital condition called hypoplastic left heart syndrome and has spent the greater part of his first year of life at Sunrise Hospital.

Macias, who celebrated his first birthday in mid-December, had to be on a heart-lung bypass machine called an ECMO for an extended period of time. The cost of that, Sunrise said, was $6,900 a day, and Sunrise is the only hospital in Nevada which offers neonatal ECMO.

He’s also has been receiving nitric oxide to help his breathing. The medicine totals $3,300 daily.

Hunting for answers

That gap between how much it costs a hospital to provide care and how much they’re paid for it is leaving Sunrise scrambling for answers. The days of cost-shifting, Sklamberg said, when a provider could tap private insurers to fill the holes in lagging Medicaid reimbursements are “long gone,” and supplemental payments through the state’s Disproportionate Share Hospital Payment (DSH) program don’t cut it.

Those payments, handed out to hospitals “serving a disproportionate share of uninsured, indigent and Medicaid patients,” according to the state, mostly go to University Medical Center, Clark County’s public hospital. UMC received 98 percent of the $70.7 million in payments to Clark County hospitals through the program for the 2018 state fiscal year, while Sunrise received the second-highest payment at nearly $216,000, or just 0.3 percent of the total.

Sunrise Hospital says it serves about one-fifth of all NICU newborns in Nevada annually. That adds up to about 1,000 babies each year.

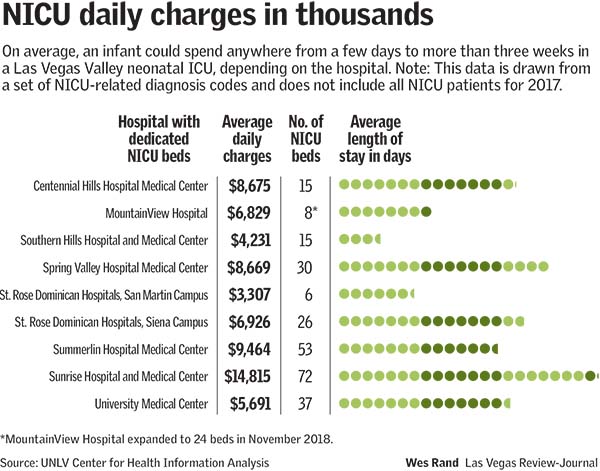

At 72 beds, Sunrise Hospital’s NICU is the largest in Clark County and the state. Summerlin Hospital Medical Center has the county’s second largest NICU at 53 beds, followed by UMC’s 37-bed unit.

Sunrise charges significantly more per patient, too. Last year, patient charges often associated with NICU care averaged $14,980 daily at Sunrise, compared to about $8,000 at Summerlin Hospital and $3,500 at UMC, according to state data. Sklamberg said the hospital serves some of the sickest babies in Nevada, which can drive up costs.

In an emailed statement, Summerlin Hospital spokeswoman Gretchen Papez agreed that Medicaid reimbursements for intensive care of infants are particularly insufficient.

“Depending upon their development and medical needs, some of these babies stay in the NICU for weeks, and even months, utilizing high-cost medical and surgical care,” the statement said. “Medicaid reimbursement levels fall short of covering hospital costs in general, and when applied to the services provided in a NICU, typically reimburse less than 50 percent of the hospital’s cost.”

Drumming up public support

Sklamerg, the Sunrise CEO, said he’s received verbal support from legislators for raising Medicaid reimbursement rates over the years. It’s a regular topic of discussion, too, among physicians, health administrators and health care workers that Nevada’s Medicaid reimbursement rates are too low to persuade more physicians to accept those covered by the state-federal plan or attract new physicians to a state where there’s a dearth in primary care.

But the verbal support hasn’t materialized into change, Sklamberg said.

Hence the Every Baby Counts campaign.

“We’re trying to talk to the community,” he said. “Before anything is shut down, the community needs to understand what that potentially means: residents will need to leave the state for care.”

The hospital has “months” before it starts looking at trimming down NICU services, Sklamberg said.

Ensuring access to such specialized care is a top priority for Nevada Medicaid, according to Nevada Medicaid acting administrator Cody Phinney.

“One of the best things that can happen is babies come into this world healthy and get the care they need when they’re born, because that will mitigate a lot of problems later as they grow up,” she said.

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.

Code-based payments not a panacea

Medicaid’s acting administrator, Cody Phinney, said the state agency will likely explore moving to a diagnosis-related group (DRG)-based model of payment by 2022 after it does an upgrade of its decades-old computer system in February and works through any issues in the aftermath.

Many insurers and state programs have made the switch to disincentivize hospitals from keeping patients longer than medically necessary, said Robert Berenson, an expert with the Urban Institute.

“It may be better to have hospitals care a little more about providing prudent care rather than trying to generate more days, so I think in that case, DRGs may create better incentives,” he said.

But there’s no data that suggests either the per diem or DRG models reimburse hospitals at a level that is closer to the actual cost of care, despite Sklamberg’s lament that the current system just isn’t working, Berenson said.