Las Vegas hospital blazes own path with malaria drug to treat COVID-19

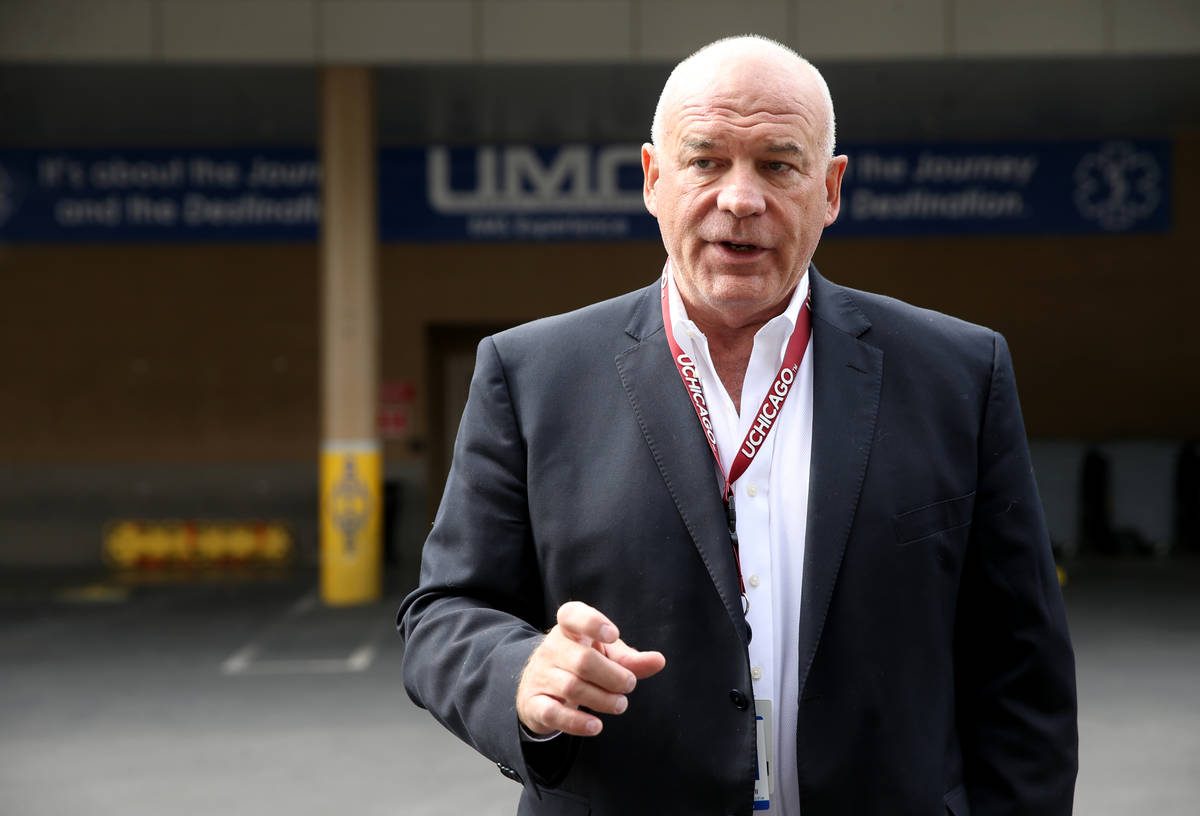

University Medical Center on Tuesday began prescribing hydroxychloroquine to high-risk emergency room patients who test positive for COVID-19 but do not require immediate hospitalization.

In doing so, UMC became the first Las Vegas-area hospital to dispense it on an outpatient basis, taking a cutting-edge position nationally in the use of the controversial experimental drug.

In a move aimed at preventing hoarding, Gov. Steve Sisolak on March 24 signed an emergency order limiting the use of hydroxychloroquine in treating patients with COVID-19 to those who are hospitalized. About a week ago, the state issued a dispensing waiver allowing hospitals to provide the drug to patients well enough to be sent home rather than admitted.

Dr. Thomas Zyniewicz, an emergency medicine physician at UMC, said the drug, which is frequently used to treat malaria and autoimmune diseases, has shown promising results in thwarting the progression of COVID-19. Two small studies out of China and France, as well as preliminary case studies across the U.S., are showing some benefit for some patients, he said.

“Our outcomes in our ICU patients to date are better than outcomes we’re seeing from Italy, China, France and other countries,” Zyniewicz noted. “Is it a result of the medication and the other antivirals we’re putting them on? Probably.”

President Donald Trump has been touting hydroxychloroquine to treat — and even prevent — COVID-19. However, the medical community, both in Southern Nevada and across the country, is divided over making the drug more widely available, noting that it has not gone through rigorous clinical trials for treating coronavirus.

That debate has been set aside for now in UMC’s emergency department, where doctors are able to test patients with fever, cough and shortness of breath for COVID-19 and get results back within hours and sometimes in a single hour, Zyniewicz said. Patients who test positive, have an abnormal chest X-ray, and are at higher risk because of age and underlying medical conditions are candidates to receive the drug and be sent home, as long as they are capable of walking, talking and eating.

‘A fighting chance’

As of Thursday, UMC had used the protocol with about a dozen outpatients, Zyniewicz said.

Across the country, he said, high-risk patients have been leaving emergency rooms and then returning four or five days later, only to require hospitalization and use of a ventilator to help them breathe.

“We were working day and night to determine if there was any therapy we could try, and this was our best resource at this time,” said Zyniewicz, a vice president with US Acute Care Solutions, a physicians group that serves more than 200 hospitals and facilities across the country.

“The patients we’re looking at first and foremost have diabetes, which is a disease that has been associated with a much worse outcome with COVID-19,” Zyniewicz said. “Now we feel very good we’re at least giving them a fighting chance to not be on a ventilator.”

Other area hospitals said they are currently using the drug only for hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Dr. Christopher Voscopoulos, medical director of the Southern Hills Hospital and Medical Center’s intensive care unit, said he has prescribed the drug to patients severely ill with COVID-19.

“When the risk of death outweighs the risk of the drug, then it is appropriate to try the drug,” he said.

From his perspective, it’s too soon to say whether the drug is benefiting patients. As for using the drug on an outpatient basis, he said he did not believe an experimental drug should be taken outside a hospital setting.

For hospitalized patients, Voscopoulos has been more enthusiastic about the early use of “proning,” or placing COVID-19 patients on their stomachs to improve lung function.

Proning is also being practiced at UMC, Zyniewicz said, along with prescribing anti-viral medications.

“Which part of our intervention was the most important? … At the end of the day, which one is the most important? We won’t know for a while,” he said.

But in a pandemic, when all drugs that could possibly benefit patients still need to be thoroughly studied, success is measured by how many people hospitals are able to get off of ventilators, he said.

“I fully expect that this therapy that we’re delivering will expand in Las Vegas and across the country pretty quickly as the production of this medication is ramped up,” Zyniewicz said, noting that UMC is the first hospital under his organization’s umbrella delivering the outpatient therapy.

In New York, a pandemic hot spot, clinical trials are evaluating the use of the drugs in patients who aren’t hospitalized.

Uses and risks

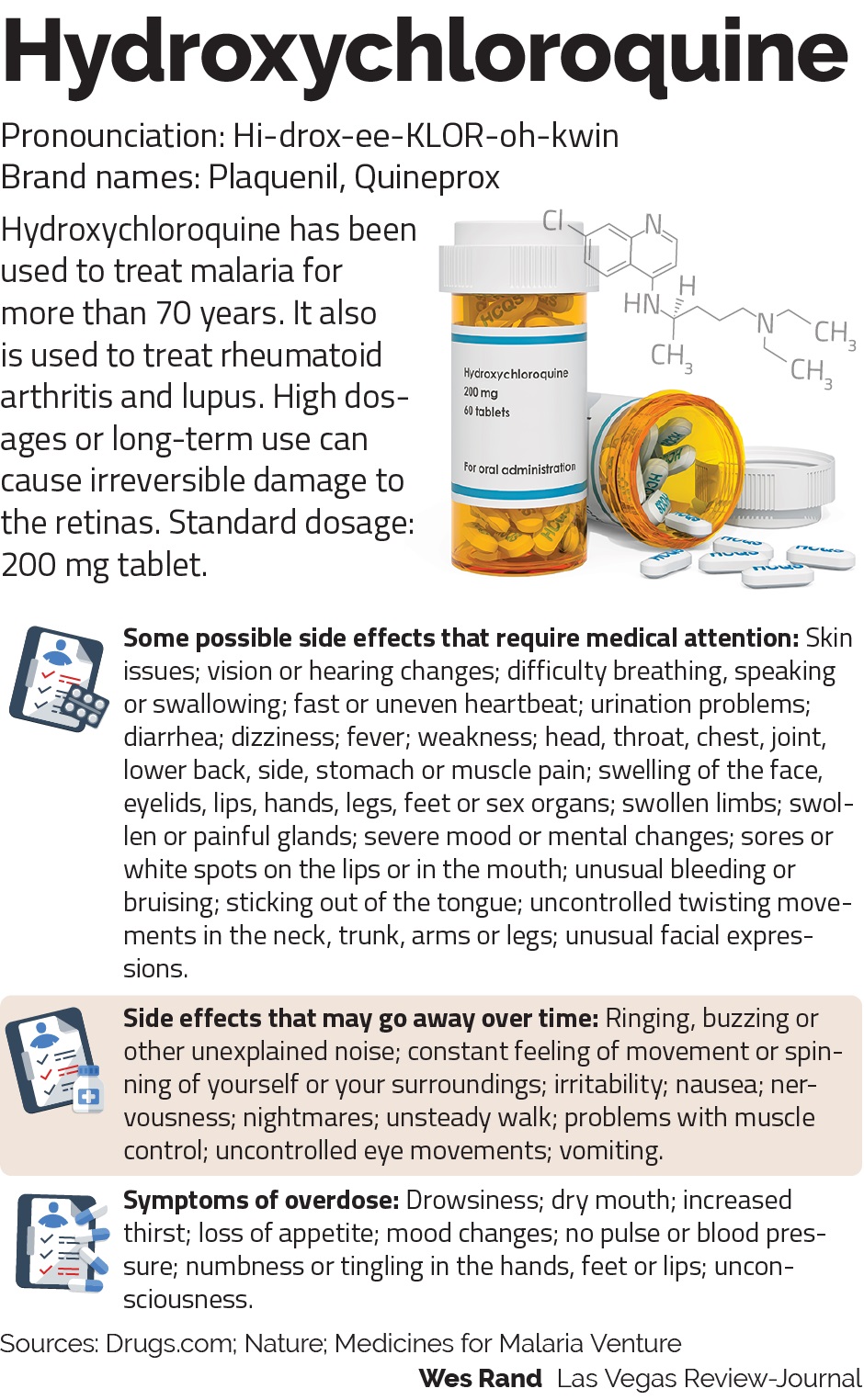

Chloroquine or its newer, safer derivative hydroxychloroquine have been used for decades to treat malaria, which is caused by a parasite. Hydroxychloroquine is also used to treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus by tamping down over-active immune systems.

The drugs have been studied in laboratories for their potential to treat viruses such as SARS, which is another type of coronavirus, and influenza, with uneven results, said Dr. David Weismiller, a professor at UNLV’s School of Medicine.

Using hydroxychloroquine “in the lab you were able to prevent the virus from infecting the cell,” Weismiller said. But outside the lab, it “wasn’t as successful in animal models and people models.”

Any drug given to generally healthy people to prevent the disease (something Trump has suggested in diverging from the advice of his medical team) should have “big double-blinded, placebo-controlled” studies behind it, said Dr. Judith Ford, medical director of clinical quality for HealthCare Partners Nevada.

The drugs, Ford said, “show potential, but that’s not how we practice medicine,” she said. “We don’t practice medicine on maybes.”

One question, she said, is “could we do more harm than good in outpatients with mild disease?”

Eighty percent of patients with COVID-19 have mild symptoms, which many argue is good reason to not prescribe an experimental drug as a preventive measure.

In guidance given to its physicians, HealthCare Partners Nevada states, “There are currently no medications that are FDA approved for prophylaxis (prevention) or treatment of COVID-19.” (The Food and Drug Administration, however, did give emergency approval late last month to a Trump administration plan to distribute millions of doses of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to hospitals across the country.)

The HealthCare Partners guidance notes that hydroxychlorquine has been used on critically ill, hospitalized patients “with some success in small numbers of patients.”

But it also notes that, among other things, the drug can disrupt heart rhythms and damage the liver.

“Using hydroxychloroquine in mild or moderate outpatient cases of COVID-19 or prophylactically for healthy people has not been recommended by any organization,” the guidance states. “HealthCare Partners Nevada medical leadership does not support the outpatient use of hydroxychloroquine at this time.”

Zyniewicz said that before giving the drug on an outpatient basis, UMC conducts electrocardiograms, liver function tests and comprehensive metabolic panels.

Doctors are engaging in “shared decision making” with patients and discussing possible side effects. “But I think the drug is quite safe, perhaps safer than a lot of other drugs we use,” he said.

“The drug has been around for 60 years … and it’s still widely used to prevent malaria,” Zyniewicz said. “I don’t know of anybody that’s going on safari that cancels their trip because they’re worried about cardiac side effects.”

Drug shortages

The governor signed the order limiting the use of hydroxychloroquine on COVID-19 after being warned by the state Pharmacy Board that hoarding and stockpiling of the drug “may result in a shortage of supplies of these drugs for legitimate medical purposes.”

Rheumatologist Dr. Scott Harris said he is getting five to 10 calls a day from patients unable to immediately fill their prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine, sometimes due to additional paperwork that is now required to prevent stockpiling and other times because a pharmacy doesn’t have it in stock.

“People are panicked that they can’t get their medication,” he said. He’s begun to talk with some patients about changing to other medications, which isn’t in their best interest when hydroxychloroquine already is benefiting them.

“We don’t want to fix something that’s not broken,” especially when the drug has not been found conclusively to to benefit COVID-19 patients, said Harris, an assistant professor at Touro University Nevada in Henderson.

But Dr. Mitchell Forman, another Las Vegas-area rheumatologist, said that despite the impact on his patients he was “thrilled” that there is a drug that could help treat “this most devastating, horrible disease.”

“I want my patients to have the very best,” said Forman, past president of the Clark County Medical Society. “On the other hand … you have this illness that is intractable, you have no prevention for it, and it impacts a significant population worldwide.”

Forman denounced any hoarding of the drug for unethical purposes, and called on pharmaceutical companies to increase its production.

But he said if he had patients with COVID-19, “I would do whatever I had to do to get them this drug,” noting that his daughter is a physician assistant in New York who has witnessed firsthand the devastation brought on by the disease.

Zyniewicz agreed that a situation often looks different to those on the ground.

“The people that are most interested in moving forward with caution are not the people that are actually seeing the patients with COVID or coronavirus,” he said.

“Certainly if you’re working here, or in New York, you want to be able to help patients,” he said. “And right now, this is the best way.”

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.