Las Vegan donates kidney to wife of 44 years

Bernardo Barnachea, a retired medical technologist and businessman, admits he was worried.

Not quite freaking out worried, but almost.

He had seen a transplant brochure from University Medical Center, read some information on a UMC website, and both said that people who wanted to donate a kidney had to be age 55 or younger.

Here he was at age 66 and in perfect health being told he couldn’t donate a kidney to the love of his life, his dear Mindy, even if his blood type was compatible.

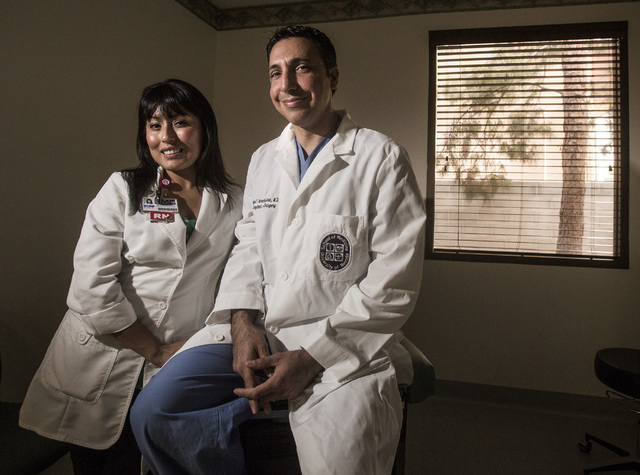

He called Arabel Dextre, the transplant coordinator, and let her know his wife, a retired nurse, just got on a waiting list for a kidney. He didn’t argue age discrimination, but she said he nervously and quickly and nicely recited results from medical tests that showed he wasn’t just healthy for 66, he was healthy for any age.

“He kept saying he knew age was an issue but he hoped it could be overcome,” Dextre said.

When Dextre could get a word in edgewise, she told Barnachea that although she was new to her position, she knew one thing for sure: the published age guidelines, not him, were too old in today’s transplant world.

There is no longer an age limit on donating a kidney as long as you’re healthy, she said, stressing that the brochures and information on the Internet had to be changed. Research showed that a donor’s health, not age, is key, she told him.

“He seemed relieved but I don’t think he felt completely sure age wasn’t an issue until he came and talked to us at the transplant center,” Dextre said. “He knew this was something he wanted to do, got all the screening done in just two weeks that showed his kidney would be a good match. That’s when I knew I was in the middle of a beautiful love story.”

The Barnacheas’ love story — they’ve been married for 44 years — added another chapter on April 14 at UMC when Dr. Bejon Maneckshana removed a kidney from Bernardo and Dr. John Ham then placed it in Mindy.

“I was so happy to do it,” Bernardo said recently as he sat in his Southern Highlands home with Mindy, now 69. “I didn’t want her to suffer, be in misery. She has such a big heart, done so much for people. Now we both feel great.”

The transplant made history at UMC, with Bernardo becoming the oldest living donor in the transplant center’s history. It is a milestone that Dextre hopes will encourage more people to come forward as living donors.

According to the United Network for Organ Sharing, about 90,000 Americans are waiting for kidneys, but fewer than 17,000 receive one each year. About 4,500 die waiting.

“We have to get more donors, first to save lives, then to save money,” Dextre said. “We changed the age guidelines at UMC about two years ago. Many people who are older keep themselves in good shape.”

The National Kidney Foundation points out that Medicare, which covers most treatment costs for severe kidney disease, saves money each time a live donor transplant removes an individual from dialysis, where waste is filtered and excess fluid removed through artificial means. Although a transplant costs more than $100,000, one year of dialysis costs $70,000. And although Medicare spends an average of $17,000 a year for the immunosuppressive drugs for a kidney transplant recipient, health experts say the health program saves more than $500,000 each time a patient is removed from dialysis.

Because donors are tested thoroughly before transplantation, a living-donor kidney is the best option for someone with failing renal function. Although half of living donor kidneys transplanted today will still be functioning in 25 years, half of cadaveric kidneys will fail in the first 10 years. But only a third of transplants nationally are from living donors.

In what is seen as an aberration in human development, people have two kidneys when they only need one to filter waste and remove excess fluid from the body. Stranger still, if one fails, the other one generally does, too.

When Mindy Barnachea had thought about a transplant — her kidneys had been failing from diabetes and high blood pressure for about 10 years and she was near dialysis at the time of her procedure — she thought about a cadaver organ. Even though her husband said he wanted to give her a kidney, she didn’t want to create possible health problems for him.

Although doctors note the vast majority of people can live normal, healthy lives with one kidney, a living-donor transplant is not completely without risk. The National Kidney Foundation has reported that as many as 2 percent of donors suffer complications, with 50 percent of those needing a follow-up corrective procedure. The chance of donor death, according to the federal government, is estimated at 0.03 percent, or three in 1,000.

“I just don’t see that as much of a risk, considering how you can help someone,” Bernardo Barnachea said. “I read so much about how a living donor kidney was better for a recipient. How could I not do that for my wife?”

Maneckshana, Barnachea’s surgeon, said his patient is “doing just fine. He’s very physically fit.”

That UMC transplant staffers are anxious to share stories about the kidney transplant process in Las Vegas — statistics show the local program functioning at better than the national rate — is a long way from how other staffers acted just six years ago, when they had a difficult time explaining quality control problems that resulted in the program being temporarily shut down.

Four deaths and a suicide within a year of transplant got the attention of federal authorities. So did UMC’s hurried promise to spend $1 million to upgrade the program, which included hiring new staff.

Today, federal statistics show the survival rate based on 136 transplants from 2011 through 2013 at 99.26 percent, higher than the average of 98.97 percent for centers of the same size.

The Barnacheas, parents of two grown sons, couldn’t be happier with their treatment at UMC. They came to Las Vegas five years ago to retire after 40 years split between Illinois and California. For nearly 20 years they ran their company, placing temporary employees at hospitals with nursing shortages in Orange County, Calif.

“We worked together for 20 years and had discussions about doing business but never fights, ” Bernardo Barnachea said.

When the Barnacheas, both immigrants from the Philippines, started courting more than 45 years ago in Chicago, Mindy wasn’t initially impressed with her suitor. A mutual acquaintance had introduced them at a party and Bernardo was smitten, he said, “by both her beauty and her big heart.”

“He was so aggressive at first, and I had to tell him I didn’t want to go out,” she said. “But when he went to school to become a medical technologist, I realized he had a brain after all. It didn’t take me long then to realize what a good man he is.”

They found they could talk about anything, had the same dreams about having children and becoming entrepreneurs. They liked the same movies, the same food. They got married in a Catholic church and had their first child a year later.

“What impressed me so much is how he’s been with her at every appointment before surgery and postsurgery,” Maneckshana said. “Their intensity of commitment to each other — she got out of bed first after surgery and went over and got him to walk the halls with her — so long after marriage is the way you want marriage to be.”

Barnachea suspects that if more people knew what he now knows, that you derive an unequaled sense of exhilaration from sharing something of yourself so another may benefit, there would be far more kidney donations from living donors.

Your life, he said, is never as full as when you’re sharing it.