Kidney Disease: Father feels guilty that son has disorder

Just a few months ago, when Juli Maloney looked at her 45-year-old husband, Bryan, she worried. His bloating made him look pregnant with twins, and his face was ashen.

He couldn’t stay awake even after sleeping more than half the day.

“I was watching my husband die a little more each day,” she said last month as she prepared to leave her Henderson home for Bracken Elementary School in Las Vegas, where she teaches first grade. “I kept praying something good would happen.”

Polycystic kidney disease, or PKD, a genetic disorder where sacs of fluid called cysts grow in the kidneys, had caused Bryan Maloney’s kidneys to fail.

Maloney’s two kidneys, each of which should have been about the size of a fist and weighed less than half a pound, had ballooned to more than seven pounds each and grown bigger than footballs.

The cysts replaced much of his kidneys’ normal structure, resulting in their having only about 4 percent of regular function. No longer could the two vital organs filter wastes and extra fluid from the blood to form urine.

Dialysis, the artificial process of filtering the blood that tethered Maloney to a machine, seemed to wear him out.

“He didn’t have any energy after those treatments,” Juli Maloney said of the entrepreneur who had opened and run baseball schools in Southern California and Las Vegas. “He was deteriorating fast. It was hard for our two sons to see him like that.”

If Juli and Bryan Maloney only had to worry about his health and what his death would mean to their two young boys, that would have been more than difficult enough to bear. But as his condition worsened, they worried even more about their 6-year-old son Kaelan. Tests had revealed he had early signs of the disease that came from his father’s side of the family.

“The whole time that my husband was going through his ordeal, in the back of my mind I was thinking that Kaelan might have to do the same thing one day,” Juli Maloney said. “It was terrifying.”

back playing ball

Today, thanks to a January kidney transplant at University Medical Center, Bryan Maloney is energetic once again, doing what he loves to do, teaching baseball through his Nevada Prospects program and playing ball with his own two boys, 9-year-old Garrett and Kaelan.

With his health no longer such a major concern, it is easier for Bryan Maloney to keep his anxiety about Kaelan’s future under wraps.

But as he watched his sons play ball last month in Henderson’s Vivaldi Park, Maloney admitted he will always have a sense of apprehension.

“I don’t see how you could not as a parent,” he said. “I felt real disappointment and guilt when I learned he had it. But I think Kaelan will be strong enough to deal with it.”

The Maloneys don’t shy away from talking about the disease with their children.

“I hope I can donate a kidney to my brother if he needs one,” Garrett said at the park when he overheard his dad talking about Kaelan and PKD.

PKD is the most commonly inherited disease in the United States; about 600,000 people have it. Children have a 50 percent chance of getting it from parents who have it.

For many people, PKD is mild and causes only minor problems. But about half of patients with PKD have kidney failure requiring dialysis or kidney transplants by age 60.

Mother’s transplant

Five years ago in Arizona, at the age of 65, Suzann Maloney, Bryan’s mother, had to have a PKD-related transplant. Though her father died at 75 and had kidney problems, no one knows for sure if he had PKD. Her mother died at age 90, and her grandparents were very elderly when they died.

“I was dumbfounded when I found I had it,” Suzann Maloney said by phone from her Arizona home. “I’m very sad my grandson has it. I hope somehow stem-cell research will help in this area one day.”

About 10 years ago, Bryan Maloney found out he had the disease after his blood pressure became very elevated. Though Maloney thought it would be a long time before the effects of the disease would really hit him, his kidneys started growing rapidly.

A test done shortly after Garrett’s birth found that the boy did not have the disease, but Kaelan’s test was positive.

Had the Maloneys known that their children would get a full-blown version of the disease, Juli Maloney said it’s possible they would not have had children.

“I don’t want to pass on pain.”

The question of whether to have children when you could pass on something that makes life more difficult to a loved one is a “tough one,” Juli Maloney said. “I do know this; when I saw that little miracle born and how he has turned out, so vital and energetic, I wonder how the world could live without him. I’m going to help him be a wonderful asset to the world. We want to be positive with him, let him do all he can.”

She has faith that even if the disease progresses in Kaelan as it did in her husband, “things will work out for the best.”

Maybe, she said, medical science will progress even further in gene therapy.

If a transplant for Kaelan becomes necessary one day, Bryan Maloney hopes his son won’t have to wait any longer than the 14 months he did.

About 88,000 Americans are on kidney transplant waiting lists, with about 4,000 dying each year before getting one. A little more than 20,000 kidney transplants are done each year, nearly 50 at UMC.

Fortunately, people can live normal lives on just one kidney.

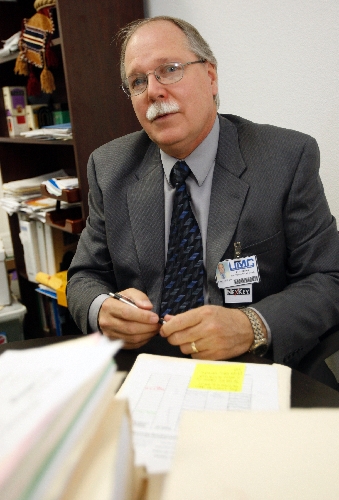

Should his son ever need a transplant surgeon, Bryan Maloney hopes the physician will be as talented as Dr. John Ham, the UMC surgeon who took out his kidneys and gave him a donated organ.

“I don’t know who the donor is,” Maloney said. “I’d like to know. I’m curious.”

Ham said because Maloney’s kidneys were so large, the transplant surgery “was more of a challenge.”

“Normally, we don’t take someone’s kidneys out in a transplant; we leave them in,” Ham said. “But in this case I thought he could tolerate that level of surgery to give him a better quality of life.”

When Kaelan hears about the surgery his dad had, and that he could have one day, he becomes uneasy. With a baseball bat on his shoulder, he tried to express what it all means to him. Finally, he just shook his head.

“I think it’s scary,” he said.

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at

pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.