C-sections: Some question whether surgery occurs only for medical necessity

If a discussion of childbirth today doesn’t include cesarean sections, it’s not natural.

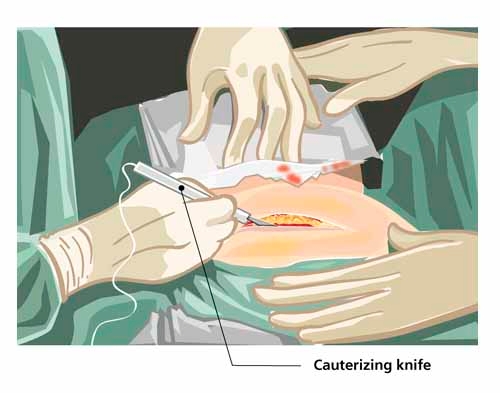

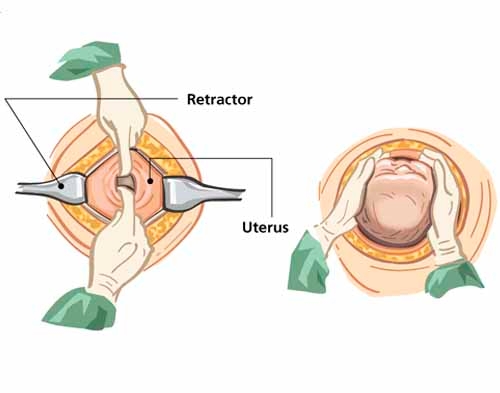

C-sections, as they are more widely known, have become the most common surgical procedure in the nation’s hospitals. And more than 1.4 million cesarean sections — the delivery of a fetus by surgical incision through the abdominal wall and uterus — are performed in the United States each year.

That translates to about one in three deliveries, with the number slightly higher in Nevada at 36 percent. The state’s C-section rate rose 72 percent from 1996 to 2007, the sixth highest increase of any state, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While a necessary cesarean can save a mother and her child from injury or death, public health officials stress it’s highly doubtful that a third of U.S. women need to have babies cut from their bellies.

Some Las Vegas women, incensed by what they believe are too many doctors cutting for convenience rather than medical necessity, have started support groups, at which they share information about how to realize a natural birth.

Though the ideal rate of cesareans is not known, the World Health Organization and U.S. health agencies suggest a number no higher than 15 percent, largely because C-sections pose a risk of surgical complications and are more likely than vaginal births to result in problems that put the infant in intensive care and the mother back in the hospital.

Those same officials note that cesareans, which result in hospital stays and charges that are both about double those of vaginal births, increase the risk of dangerous abnormalities in the placenta during later pregnancies, which can cause hemorrhaging and lead to a hysterectomy.

Why the staggering increase in C-sections the past four decades? They were at just 4.5 percent of births nationwide when first measured in 1965.

The medical reasons for the procedure have remained largely the same:

■ A labor that fails to progress.

■ A baby has reduced oxygen supply.

■ A baby is in breech, feet or buttocks first, or transverse, side or shoulder first, position.

■ The mother is carrying multiples, such as twins or triplets.

■ There are problems with the placenta or umbilical cord.

■ A baby has a large head.

■ Mom or baby has a health condition.

The CDC concluded that in addition to clinical reasons, the increase can also be explained by nonmedical factors, including physician practice patterns, legal pressures, maternal choice, more conservative practice guidelines and the older age of women.

Dr. Jerry Reeves, vice president of medical affairs for Health Insight, a nonprofit community based organization dedicated to improving the health care systems of Nevada, New Mexico and Utah, has come to his own conclusion.

"One of life’s miracles is being reduced to an epidemic of unwarranted profitable major surgical procedures with serious complications, too often for the convenience of the surgeon," he said. "And vulnerable expectant mothers are not in a position to challenge the recommendations of the obstetrician."

CESAREAN SECTION GUIDELINES REVIEWED

In 2010, nearly 34,000 children were born in Nevada, more than half of them in Clark County. More than 12, 000 were by C-section.

Of those C-sections, more than 46 percent of the mothers were repeat customers. A long-held belief of many physicians, one debated by a growing number of women, is that in the interest of safety, once a woman has delivered by C-section, any future babies should be delivered that way, too. Doctors are concerned about a life-threatening rupture at the scar left by a previous cesarean.

In 2010, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued new guidelines designed to make it easier for women to find doctors and hospitals that allow a vaginal birth after cesarean, or VBAC. An Australian study released three weeks ago, however, is sure to heat up the debate over VBACs. While the complication rate was low for both, natural birth after a C-section is slightly riskier than repeat surgery, the study showed.

In an editorial accompanying the study, Dr. Catherine Spong of the National Institute of Child Health and Development, wrote: "In the end, the onus falls on the clinicians. … Neither the patient nor the clinician would have to fret about whether to attempt a trial of labor or choose a repeat cesarean if the first cesarean had been prevented."

Reeves’ contention that C-sections in Nevada aren’t always done for medical reasons is partly based on the state’s hospital discharge data.

Dr. K. Warren Volker heads the largest ob-gyn group in Southern Nevada, with more than 39 providers at eight locations. He agrees there are "unfortunately" doctors doing C-sections for convenience and on demand: "Even though it is a common surgery, there is an increased risk of complications. It is, after all, major surgery."

Potential C-section complications for moms include infection at the incision site, in the uterus or in other pelvic organs, such as the bladder; more blood loss, which can lead to anemia or a blood transfusion; possible injury to organs such as the bowel or bladder; and scar tissue or adhesions that can lead to future pregnancy complications.

Reeves, 54, terms the high C-section rate "overmedicalization" and offers charts and graphs.

In 2010, for example, the C-section rates at Spring Valley, Summerlin, Southern Hills and St. Rose Dominican Hospital-Siena — all Las Vegas Valley hospitals that largely cater to insured patients — were above 41 percent.

Yet University Medical Center, which sees more low-income patients, many of whom don’t receive good prenatal care, had a rate of 29 percent.

"Something doesn’t add up," Reeves said recently. "You would think that low-income patients who usually don’t have as good of prenatal care would require even more C-sections than those with good prenatal care."

Ninety percent of those who received a C-section in Clark and Washoe counties were insured while just 29 percent of uninsured patients received C-sections.

"It seems obvious that the better off a woman is, the better her chance of receiving a C-section," Reeves said.

The hospital discharge data also show that between 93 percent and 97 percent of C-sections and vaginal deliveries in both counties were in the mild or moderate severity categories.

From 2004 to 2010 in Clark County, when obstetricians handled more than 155,000 cases, 10 women died during 55,940 C-sections compared to four who died during 100,275 vaginal deliveries.

Vaginal births, of course, are not without risks. Even a spontaneous vaginal birth can cause a painful vaginal area and urinary and bowel incontinence for the mother, and weakness and lack of motion in the arm of an infant.

In most instances, those problems resolve shortly after birth.

Using forceps or vacuums in an assisted vaginal birth can cause brain injury in an infant and injuries including bowel and sexual difficulties for the mother.

Still, vaginal births only resulted in a 4.5 percent complication rate compared to a 9.5 percent complication rate from cesarean sections during the six-year period ending in 2010.

"Women who are going through the birthing process need to be fully informed of the risks and benefit of C-sections compared to vaginal delivery," Reeves said. "It’s major open abdominal surgery."

And major surgery, of course, comes at a high price.

At Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, moderate C-section deliveries, those with no major challenges, ran up hospital charges of more than $25,000 each, compared to vaginal deliveries at about $12,000.

C-sections, according to Reeves, end up becoming a profit center in many hospitals, so there’s not much incentive to reduce them.

But Chuck Duarte, administrator of the state’s Medicaid program, said state officials are looking at policy changes that could remove financial incentives for doctors to do C-sections at government expense, which he believes will reduce the financial burden on taxpayers.

He said doctors who do unnecessary cesareans, often inducing labor before 39 weeks, will be paid the same as doctors who perform a normal vaginal delivery, $1,599. That’s a drop of $586.

Hospitals where unnecessary C-sections are performed will also be paid at the normal vaginal delivery rate of $1,140 per day for the mother and $312 for the newborn. Patients who have a normal vaginal delivery generally go home in less than two days, while those with C-sections stay more than three days.

"It can be a significant cost saving," Duarte said. In fiscal year 2010, C-section costs were more than $9 million for less than 1,900 deliveries while nearly 5,000 vaginal deliveries were $15 million.

Spokesmen for local hospitals say their administrators do nothing to encourage doctors to perform more expensive C-sections and that those decisions are made between doctors and patients.

Reeves said he doubts many physicians do C-sections for the primary reason of earning a few hundred dollars more. Private insurance, like Medicaid, pays a little more for a C-section.

He notes, however, that elective C-sections can be scheduled well in advance, allowing the doctor to see more patients and increasing the doctor’s bottom line.

The practice variations of doctors fascinate Reeves. He pointed to documents showing the C-section rate of four doctors, none of whom had a practice specialized in high-risk pregnancies, thus requiring cesareans. Two had C-section rates of more than 65 percent while the other two had rates less than 24 percent.

"They all can’t be right," he said. "If C-sections were done only for medical reasons, one would expect the rates to be more in line. It appears that too many C-sections are done predominately for the convenience of the physician."

Reeves said it isn’t difficult for a physician to talk a woman into a C-section, particularly if she hasn’t researched what to expect in childbirth: "Any new mother who wants what is best for the baby is going to do what the doctor suggests is in the baby’s best interest."

Reeves noted that C-sections take less than an hour, while labor for a vaginal delivery can last 12 hours or more.

Convenience, Reeves said, isn’t just something cherished by physicians. Obstetricians, he said, will receive calls from patients requesting the scheduling of elective labor inductions months in advance, at a time when the patient knows the doctor will be in town.

"Natural childbirth proceeds when the body is ready," Reeves said. "Early inductions of labor and C-sections can be scheduled when the mother and doctor are ready. They are not mutually compatible."

SUSPECTING SURGERY FOR CONVENIENCE

Everything had gone right with Chelsea Robbins’ first pregnancy. She was in great health at 24, worked at her jobs as a receptionist and photographer until she was 36 weeks along, and enjoyed evening walks with her husband, Dustin, right up until she was 38½ weeks.

It appeared her dream of a natural childbirth would come true.

One day she started to feel a few slight contractions so she went to the nearby Rose de Lima campus of St. Rose Dominican Hospital in Henderson.

"I knew I wasn’t in full labor but just wanted to check and see what was going on," she said. "I was excited."

A nurse monitored her irregular contractions for about an hour.

"Everything was fine," Robbins recalled recently as she waited to participate in a support group at Well Rounded Mama, a center on South Eastern Avenue that’s devoted to helping women find the right childbirth choices. "The baby’s heart was fine. There was no fetal distress. I just figured I’d be sent home."

When the nurse called a doctor in her physician’s medical group — her own doctor was on vacation — Robbins had little concern. Then the nurse said the doctor wanted her to be induced.

"She never really said why, just that the doctor thought it would be best," Robbins said. "I was stunned."

Robbins and her husband wanted to go home and wait for labor to come naturally, but nurses advised against it. If Robbins disregarded the doctor’s instructions, she would be liable if anything went wrong.

Assuming that the doctor must have her best interests at heart, Robbins let nurses give her a drug to speed up contractions. The contractions became strong enough to require two epidurals for pain but not strong enough for her to deliver a baby.

After several hours, the doctor performed a C-section because of Robbins’ "failure to progress."

"I believe now this was all for the convenience of the doctor," Robbins said. "It was a gruesome surgery cutting through my stomach muscles. I couldn’t even see my baby at first.

"It took me three or four weeks to get over the surgery. I could hardly get out of bed myself. I didn’t like not being able to nurse or carry Conrad at first. I really think that C-section caused my post-partum depression."

A study released in 2010 by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development found C-section rates were twice as high after induction of labor compared with women undergoing spontaneous labor. The study suggested that doctors aren’t acknowledging that labor takes time and doesn’t follow a predictable pattern in women, especially first-time mothers.

About 20 percent of labors are induced, according to national studies.

"Believe me," Robbins said. "If I had an emergency and my baby’s life was at stake, I’d say cut me open right now. But that wasn’t the case. This was a doctor who felt she was dealing with a young naive mother who didn’t know any better and wanted something done on her schedule. It’s just not right."

When Michelle Van Norman was halfway through her second pregnancy in 2005, her doctor asked whether she wanted to schedule her C-section delivery date.

Because her first child was born by cesarean and her doctor subscribed to the "once a C-section, always a C-section" dictum, Van Norman didn’t find the doctor’s request unusual.

And because her physician told her that the baby would be fine, the Las Vegas woman agreed to have the delivery 11 days earlier than her due date.

"There were no medical reasons for the delivery being early," Van Norman told a number of families that had gathered at Well Rounded Mama. "He just said when he could do it, and I figured it was a more convenient time for him."

It might have been convenient for the doctor, Van Norman said, "but it wasn’t convenient" for the little boy she and her husband named Christian.

After his birth by C-section at Mountain View Hospital, one of his lungs collapsed. Because of the severity of his case, Van Norman said, her son was transferred to the intensive care unit at Sunrise Hospital. He spent three weeks in ICU and 10 days on a ventilator with six tubes going into his chest.

"I didn’t get to see him for days because I was stuck in another hospital," she said.

Van Norman wept as she talked. So did many of the 25 mothers on hand.

"The whole first year of my baby’s life was horrific," she said. "And my husband and I still don’t know if the oxygen deprivation had any effect on him. My son should never have been born that early. I swore from that day on I would never put another baby through that kind of torture for any reason."

Van Norman’s surgeon declined comment on the case.

HOW INFANTS CAN BE AFFECTED

Babies born early through C-section without a medical reason are about twice as likely to spend time in the neonatal intensive care unit, researchers say. A 2009 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that they also are more likely to contract infections and need the assistance of breathing machines.

Van Norman’s experience is an example of why the March of Dimes has pushed its "Healthy Babies are Worth the Wait" campaign nationwide. It argues that "at least 39 weeks is best for your baby."

The campaign warns that having babies before that includes a significant increased risk of an infant requiring intensive care and ventilator support. Studies stressed by the campaign show that rates of respiratory complications were 14 times higher in pre-labor cesarean birth at 37 weeks compared with 40 weeks gestation, and 8.2 times higher at 38 weeks.

Many experts consider the optimal length of pregnancy to be 40 weeks, when the brain and lungs are fully formed.

According to researchers with the CDC, the average time a fetus spends in the womb has fallen seven days in the United States since 1992, which experts call an "evolutionary dramatic event."

A 2007 study of nearly 18,000 deliveries found that 9.6 percent were early births — through scheduled inductions or C-sections — for nonmedical reasons.

"A C-section can cause problems for your baby," the March of Dimes literature warns. "Babies born by C-section may have more breathing and other medical problems than babies born by vaginal birth."

Cuts from medical instruments also can occur with newborns delivered by cesarean sections.

"Research clearly shows that it’s better for the mother and the baby when a delivery comes when it’s naturally supposed to come," said Michelle Gorelow, director of program services for the March of Dimes in Las Vegas.

DOCTORS POINT TO LIVES SAVED

Dr. John Nowins, president of the Clark County OB/GYN Society, isn’t enamored of the numbers that health officials have targeted as promoting the best results in childbirth.

Rather than back the CDC and World Health Organization, which push for no more than 15 percent of childbirths done through C-sections, he says the correct number is what the patient and doctor agree on to have a healthy baby.

"It’s hard for me to be critical of C-sections because they’ve saved so many lives," he said. "All I can say is thank God our ob-gyns know how to do them. They’ve saved babies and even the mom. They’ve gotten much safer over the years. What we want is a healthy baby, plain and simple."

Magdalena Alvarez, a midwife who helps run Pink Peas, a pregnancy care center at 3920 W. Charleston Blvd. that strongly advocates for natural childbirth, agrees that safe C-sections are important.

She said a C-section saved both her life and that of her second baby.

"I strongly believe in natural childbirth, and by that I mean in the home," she said. "But I also strongly believe in C-sections in emergencies, when they’re medically necessary. That’s what they’re fundamentally supposed to be for."

Alvarez had a condition known as placenta previa, where the placenta totally covered her cervix, the doorway between the uterus and the vagina.

"It was discovered during an ultrasound," said Alvarez, mother of seven children, five of whom were delivered at home after she had a C-section. "If I hadn’t had the C-section, the baby and I both would have died."

But when a doctor says, "What we want is a healthy baby, plain and simple," she worries that a doctor isn’t trying for childbirth without surgery.

"That’s not right," she said. "A mother can’t really bond with a child during a C-section and she also has to go through major surgery. So C-sections should only be for emergencies, nothing more."

Nowins says it’s not unusual today to find women who opt for the convenience of a C-section. Relatives might be in town or they might want to make sure their own doctor isn’t on vacation. And he says that babies have long been considered full term between 37 and 40 weeks.

"The reason the March of Dimes is emphasizing 39 weeks now is women not getting proper prenatal care," he said. "But if you have a woman who got an ultrasound early in her pregnancy so we can accurately date her pregnancy, there isn’t a problem."

Nowins also disputes that doctors frighten their patients into C-sections when they are in labor: "The doctors I know are always going to try to do what’s best for his patient. A patient can always go to the charge nurse if she has a problem with a doctor. And that nurse can make sure that behavior stops."

DOCTORS RUN THE OPERATION

While that advice might work in theory, Las Vegas registered nurse Christy Seekatz says the charge nurse will seldom, if ever, side with a patient against a doctor.

"She works with the doctor all the time," Seekatz said. "And she’s around the patient one time. Now who do you think she is going to try and keep happy?"

Seekatz said a doctor talked her into a C-section when she didn’t need one. Doctors lobby for C-sections for their personal convenience or because scheduling cesareans allows them to have more patients, which increases their income, she said.

"They basically see women as ignorant of the process, and too many of us are," she said. "I’m a nurse and I was terrified. When the doctor said there could be a problem with the baby’s heart rate — not that there was — I went along with whatever the doctor said. But women have to become more educated so doctors can’t push them into things just so they can go home."

Nowins, however, contends it is unfair and unjust to think that doctors have anything other than the best interests of their patients at heart: "I know a lot us who are still up in the middle of the night delivering babies."

Nowins said doctors also have to consider potential liability. It is unfortunate, but true, that some babies are simply born with problems. And if that child is taken in front of a jury, he said, empathetic jurors will blame the doctor.

To protect themselves when challenges arise, Nowins said, doctors opt for C-section, which shows a clinician took action at the first sign of a problem.

Dr. Tammy Reynolds, an obstetrician who had her first child by C-section and her second vaginally, agrees that doctors practice defensive medicine in part to protect themselves from liability.

She believes many doctors, fearful of being sued if there is harm to a baby after a normal labor and delivery, might be quicker than they were in the past to perform a cesarean.

Though fetal heart rate monitoring is far from precise, with rates of heartbeats variable, Reynolds noted some obstetricians will use a monitoring strip that can be interpreted as a sign of full-time distress to convince themselves and patients a C-section is necessary.

"You can wait, and most of the time everything will turn out all right," Reynolds said. "But we’re told that we’ll seldom get sued for doing a C-section when there could be trouble, but we’ll always be sued if we don’t."

Obstetrician Steven Harter concurs that defensive medicine is regularly practiced. With malpractice insurance rates ranging from $85,000 to $200,000 a year for obstetricians, he said physicians who deliver babies fear "the one big suit that can take away their malpractice insurance for good."

"They put hundreds of thousands of dollars in their education, and they don’t want to be wiped out," he said.

At least one well-known malpractice attorney said she is unaware of ob-gyns carrying out C-sections to protect themselves from liability.

Las Vegas defense attorney Kim Mandelbaum, who has represented about 2,000 doctors in malpractice cases, said she has never had a doctor tell her that he or she did a C-section as protection against liability.

"The doctors I’ve worked with tell me they don’t want to do surgery unless they absolutely have to," she said.

Still, a study done by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists supports what Reynolds and Harter say about physicians’ liability concerns.

In 2009, 63 percent of ob-gyns in the study group made changes in their practices because of the risk of liability claims, with 29 percent increasing the number of C-sections.

That same research found that more than 90 percent of ob-gyns have been sued at least once during their careers, with about 30 percent of the claims related to a neurologically impaired infant. Of these, nearly 50 percent resulted in an average payment of $1.1 million.

While that research is compelling, it doesn’t speak to whether insurance companies actually favor physicians performing C-sections as a way of fighting off possible lawsuits.

Jim McMahon, risk manager for Premier Physicians Insurance Co., which insures a number of Las Vegas doctors for malpractice, said his company would not encourage doctors to do C-sections unless totally warranted.

"It is major surgery with liability risks of its own," he said. "Believe me, you don’t get a discount for doing them."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.

Part 2Las Vegas doctors, women try to change C-section approach