Brain surgery helps Parkinson’s patient control symptoms

Less than three years ago, Ken Perrigo’s problems with balance often had him crashing to the floor. To get around the house safely, he began crawling. He was so stiff it would take him nearly an hour to go the short distance from one room to another.

He frequently couldn’t get into bed by himself. The bathroom was a challenge he couldn’t handle alone.

Trembling and weak, he couldn’t cut his own meat at the dinner table.

Outside, he used a wheelchair to get around.

He took 22 pills a day in an effort to control the tremors and rigidity of Parkinson’s disease, but the medication gave him the same erratic, spastic movements that people often associate with the actor Michael J. Fox, who also has the disorder.

On Wednesday, as he now has done regularly for almost two years, Perrigo headed out to the Painted Desert Golf Club in northwest Las Vegas. His 25-year-old son Kevin drove him, but Perrigo carried his own clubs at the driving range.

He was walking and standing tall, a slim and trim 6-footer with a smile on his face, not a twitch. The only shaking he did came when he shook hands. The strength of his handshake made it obvious he can now deal with a T-bone steak.

At first, his drives sliced right. But then one ball after another went straight down the middle.

"What happened to me was miraculous," he said slowly and softly, his speech slightly impaired. "I’d say I’m 90 percent better. I don’t take any medication at all now."

"It really was a miracle," Kevin said.

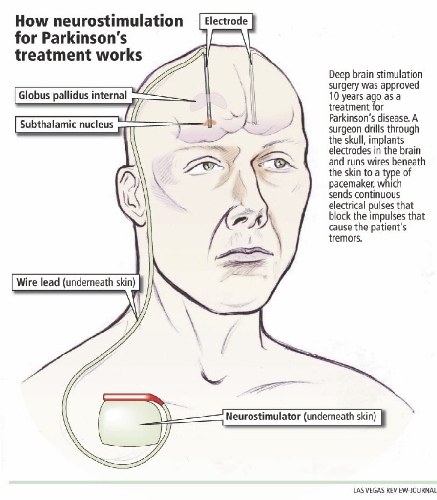

A surgery known as deep brain stimulation — the 53-year-old Perrigo has electrodes implanted deep in his gray matter that jam dysfunctional signaling in his brain — has transformed his life.

Now he goes shopping with his wife, attends school events for his daughter. The night life of Las Vegas once again can be a joy. He has taken up bowling again.

The former chief financial officer for a national auto loan firm said he has come forward now to talk about his experience to let others with Parkinson’s disease know that there can be hope for managing the disorder’s debilitating symptoms.

"Hope is important," he said. "But it’s also important for me to say that the surgery is not a cure. The disease still progresses."

Around 1 million people in the United States have Parkinson’s. Symptoms usually appear when someone is older than 50, but Perrigo was 39 when he was diagnosed.

The exact cause of the disorder is unknown, but it has been around for a long time. In 1817, the physician for whom the disease is named, Dr. James Parkinson, called it "shaking palsy."

A disorder of the central nervous system, Parkinson’s causes an individual to lose the ability to totally control body movements.

Deep in the brain, nerve cells known as basal ganglia help control movement. In an individual with Parkinson’s, these nerve cells, which make and use a brain chemical called dopamine, are damaged.

Dopamine sends messages to other parts of the brain to coordinate body movements. In someone with Parkinson’s, dopamine levels are low, so the body doesn’t get the right messages it needs to move normally.

There are experts who believe the disorder is inherited and others who believe there is something in the environment, such as a virulent pesticide, that causes the nerve damage.

Sitting in the office of Dr. Eric Farbman, a neurologist at University of Nevada School of Medicine, Perrigo said he was unaware of either a genetic or dangerous chemical catalyst for his Parkinson’s.

What he knew was that he was sitting at the kitchen table a little over 10 years ago and a tremor in his left hand caused him to spill a cup of coffee.

The shaking and rigidity on his left side spread to his right. He was diagnosed with the disease in 1999.

"Malena (his wife) and I cried," he said. "It was even harder to tell my mother. She had no idea I was having a problem."

As the disease progressed, Perrigo said his children, Kevin, Scott and Nicole, worried that they would lose their dad.

He had to leave work and go on disability.

For a while his medication, levodopa, helped relieve symptoms, correcting the shortage of dopamine. But as time passed, the medication itself caused dyskinesia, a jerky, dancelike movement of the arms and head.

Only for about an hour a day, at best, did he feel normal.

Two years ago, unhappy with his neurologist, he visited Farbman in a wheelchair.

Almost immediately Farbman, whose speciality is movement disorders, thought Perrigo was a perfect candidate for deep brain stimulation. He didn’t have the dementia or other cognitive deficiencies that some Parkinson’s patients suffer from, and the large amount of medicine he was taking wasn’t having the desired effect.

"My other neurologist never told me I could be a candidate for brain surgery," Perrigo recalled. "I’m afraid there are others out there in the early stages of Parkinson’s that don’t know about this."

When Farbman broached the subject of deep brain stimulation, which had been approved by the Food and Drug Administration 10 years ago as a treatment for Parkinson’s, Perrigo didn’t immediately go for it.

Although the risk of death from the procedure is less than 1 percent, it carries other risks.

Farbman told Perrigo a patient he had at the University of Pittsburgh suffered a stroke.

There is also the danger of intracranial bleeding, seizures, infection, nervous system disorders, psychiatric disorders, device related complications and cardiac disorders.

A Veterans Affairs study of 255 patients with Parkinson’s disease during the last decade found that the overall risk of experiencing a serious adverse event was 3.8 times higher in deep brain stimulation patients than in patients who just took medicine.

"It was a difficult decision to make," Perrigo said. "After all, it’s brain surgery, where someone is drilling into your head and fishing around."

What caused Perrigo to opt for surgery is that researchers also have found that after six months brain stimulation patients gained an average of nearly five hours a day of good symptom control, while patients on medicine had no change. The brain surgery patients also took less medication.

When Perrigo gave Farbman the go-ahead, the neurologist contacted neurosurgeon Dr. Aury Nagy, who performed the procedure at Desert Springs Hospital in 2008.

"I had great anticipation, but I tried not to be overly optimistic," Perrigo said.

He recalled that Michael J. Fox had a different kind of brain surgery that didn’t alleviate all of his symptoms. Fox has said that he won’t have any more surgery unless it’s a cure.

On the first day of Perrigo’s procedure, Nagy used computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging to precisely locate the target in Perrigo’s brain.

The next day, with Perrigo’s head held firmly in a sophisticated vise, he drilled, implanting electrodes in Perrigo’s brain.

"We had to make sure we didn’t hit blood vessels," Nagy said.

Perrigo was awake for much of the procedure. As strange as it may seem, patients feel no pain as a surgeon works inside the brain. Perrigo was under anesthesia, however, during the drilling through his skull.

The electrodes in Perrigo’s brain are connected by wires to a type of pacemaker device that Nagy implanted under the skin of his chest. The device was activated after Perrigo was given about a month to heal from the procedures.

It sends continuous electrical pulses to the target areas of the brain, blocking the impulses that cause tremors.

Shortly after it was activated, Perrigo went home.

And then he stood up and walked around the block.

"I had an incredible sense of freedom," he said. "What I went through was all worth it."

Neither Nagy nor Farbman have seen a patient respond to deep stimulation the way Perrigo has.

"To get completely out of a wheelchair and off all medication is pretty much unheard of," Farbman said.

Just how effective the electrodes are became apparent when Farbman shut off the pacemaker device to one side of Perrigo’s body. Within seconds, he was trembling, seizing up with involuntary movements. Turned immediately back on, he again was calm.

Perrigo, who is fluent in English and Spanish, said he may have experienced some cognitive decline since the procedure.

"I believe I’m thinking just as well, but I can’t always get what I’m thinking out of my mouth," he said.

He also has found that his face doesn’t express emotion as well. And he has found himself drooling.

"There is a downside to the procedure," he said.

Farbman isn’t sure that the procedure has caused any of the problems that Perrigo associates with it.

"You have to keep remembering that deep brain stimulation is not a cure," Farbman said. "The disease continues to progress."

While Parkinson’s itself is not a fatal disease, patients eventually may become severely incapacitated and unable to move or care for themselves. Difficulty swallowing caused by the disorder can lead to aspiration of food in the lungs, which can cause pneumonia and other fatal pulmonary conditions.

How long Perrigo will continue to enjoy his present state of health is anybody’s guess.

"This brain surgery hasn’t been around that long, so we really don’t know what the future holds for him," Farbman said.

Perrigo stays on top of research into a cure for the disease.

The use of stem cells, once thought to hold much promise in combating the disease, still seems a long way from reality, he said.

He is happy that the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas is part of a clinical trial studying the effect of exercise on Parkinson’s.

"We don’t know what the next big step after brain surgery is going to be," Perrigo said.

Still a relatively young man, Perrigo said he wants to be alive when his youngest child, 16-year-old daughter Nicole, gets married.

"She’s one of the top students in her class at Bishop Gorman High School. I’m just hoping she waits to age 28 to get married," the proud papa said.

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.