A crisis quietly unfolds in Clark County hospitals

Kenya Young paced in the back parking lot of Valley Hospital Medical Center.

It was Monday afternoon, warm and sunny. Someone had painted glowing white candles and blooming poinsettias on the windows surrounding the hospital’s main entrance.

At the ambulance bay and emergency department, though, there were no festive decorations. It was clinical, quiet. No line of people waiting outside, no sign of crowds within.

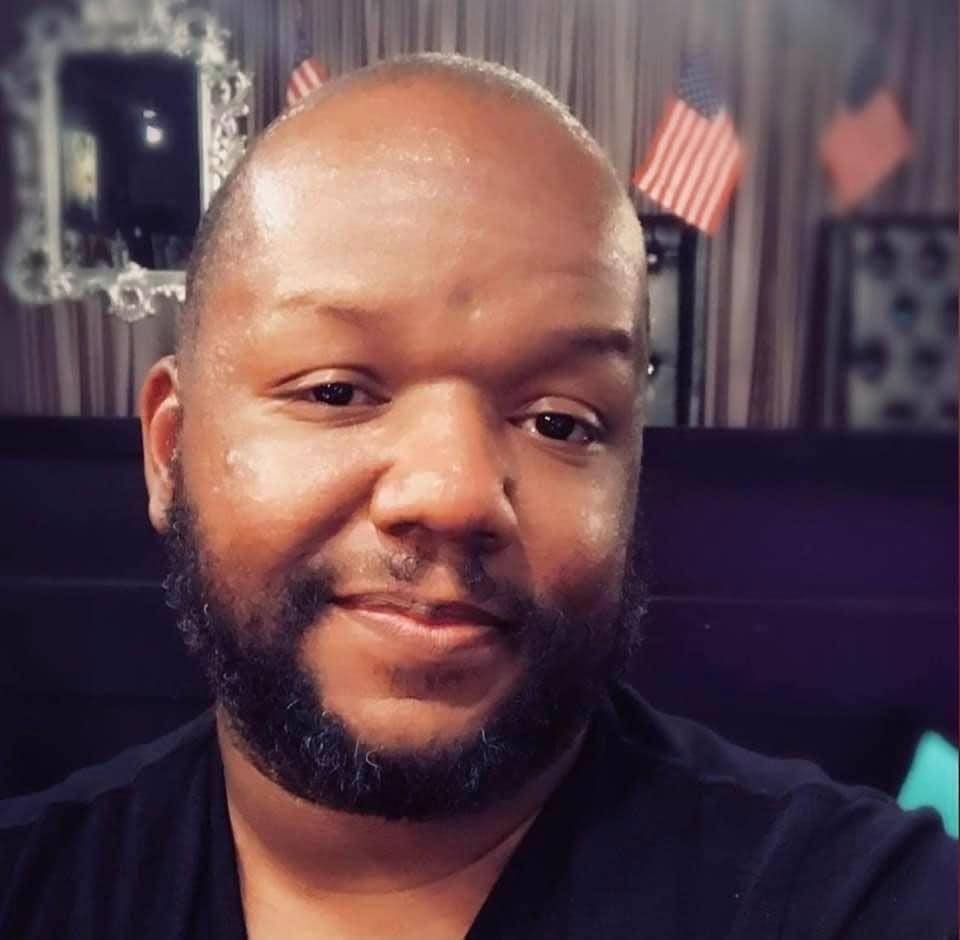

Young steeled herself. Having parked in the wrong lot, she walked over to University Medical Center, where her brother lay in an ICU bed, about to die. Marlon Young, 40, had gotten sick with COVID-19 only a week earlier, while working as a cabdriver.

There was a light breeze. Young, 39, was confused, angry, allowed into the hospital for the first time only to say goodbye.

On the ICU floor, staring at her brother’s weak body through glass, she sang “Fly Like An Eagle” by Steve Miller Band. She doesn’t know why; it just came to her, Young said. She was the only visitor in the unit of about 10-15 other patients, each in their own room, connected to machines and monitors. She was alone in her alertness, aside from the strangers in scrubs.

It took about five minutes for him to die once he was disconnected from life support. There was no fanfare, no announcement, nothing but a kind nurse to acknowledge that her older brother — the one she and her six other siblings had grown up with in foster care — was now dead. Just one of more than 2,800 Nevadans the coronavirus has claimed since March.

■■■

Records show the pandemic continues to rage in Nevada.

But drive past a hospital emergency room, or walk up to a main entrance, and it’s hard to tell. Review-Journal reporters who visited 15 valley hospitals early Tuesday reported no lines outside and no evidence of long ER wait times.

At urgent care clinics, where some go to get tested for the coronavirus or seek treatment for other ailments, the ongoing public health crisis is also not obvious. Reporters counted lines of 10 to 30 people outside before business hours, but most of the queues dissipated when clinics opened for the day.

The quiet and calm outside both facilities is deceptive, knowing that inside the hospitals, where frontline hospital workers are being pushed to their limits by the COVID-19 surge, life and death decisions are being made every minute. This, despite the Nevada Hospital Association’s assurances that the region’s hospitals have room to take on more patients.

Celia Nieto, an ICU nurse of 15 years at St. Rose Dominican Hospital, Siena campus, in Henderson, said Tuesday that all 26 staffed beds in her unit were filled with COVID-19 patients.

“What we’re seeing currently is the worst it’s ever been during this pandemic,” she said. “We’re pretty stretched thin.”

Nieto called it “controlled chaos,” saying she had heard talk of rationing care. And she worries about the weeks after Christmas and New Year’s Eve.

“I do anticipate it getting worse,” she said. “I’ve seen death, grief and trauma like I’ve never seen in my career.”

■■■

Even if you do not fall ill with the coronavirus, the COVID-19 surge continues to affect urgent care in the Las Vegas Valley.

Some hospitals have delayed or reduced elective surgeries, which can range from kidney stone removal to organ transplants. In the coming weeks, facilities may be forced to consider canceling the procedures altogether, said Brian Labus, assistant professor of epidemiology at UNLV.

Expectant mothers have had to pick and choose who can be present when they give birth amid coronavirus visitor restrictions. And in moments of crisis, when life hangs in the balance, families like that of Vinston Fortee Davis Jr., 26, cannot surround bedsides.

Davis was hospitalized in critical condition in UMC’s trauma unit this week for reasons unrelated to the virus. On Sunday, hospital staff allowed his girlfriend and relatives to see him two at a time.

But on Monday afternoon and into the night, the admissions were paused. Nine adults and three children were camped out in folding chairs in the parking lot, waiting for word as prayer candles burned at their feet.

With Davis in a ground-floor bed near a tall window, they took turns giving each other boosts, so relatives could at least catch a glimpse of the young man. One at a time, they pressed their faces to the glass.

■■■

Where do we go from here: Nearing the brink but not on the edge just yet — beds filling up but not full?

“It kind of depends on the behaviors and how people interact,” Labus said.

Nevada is entering a dangerous period in what is supposed to be a joyous season. The approval of new vaccines gave hope. But distributing doses will take time, and the holidays are here now, bringing with them the possibility of “superspreader” events aplenty.

“It’s not the resorts. It’s not the restaurants. It’s not the grocery stores,” UMC CEO Mason Van Houweling said Tuesday. “It’s the very close-knit gathering with families and others that we have to be beware of. You don’t look at your family as a threat, but this virus can be very silent especially when it’s asymptomatic.”

Wear a mask. Keep your distance. The guidance has not changed. But the situation, even if you can’t see it, is more dire.

Without a dent in current trends, Clark County will have to get creative. It’s a gentle way of saying beds may move to parking garages or convention centers, and staff may have to decide who gets treatment and who does not, based not on need but space, resources and staff.

“The endgame is getting a large enough percent of herd immunity so we have protection for the rest of us,” Labus said, something that likely won’t happen until the summer.

■■■

In the parking lot of Nucleus Plaza on Tuesday, in the Historic Westside, Kenya Young hosted a charity coat drive the day after her brother’s death.

She had planned it weeks in advance, before he got sick. She was angry and hurt but couldn’t bring herself to cancel.

People in masks browsed the free selection, hanging on racks under a small white tent. Others stopped to make a donation, a portion of which was set aside for foster children, just like her and her siblings growing up. Music played.

She talked about how quickly COVID took him. The fight for information while he was hospitalized. The frustration of not being allowed by his side until it was time. She talked about the drive and the good she hoped it would do for the community. Then they needed her at the tent.

“I hate COVID,” she said before walking away. “And I was skeptical at first — I didn’t think it was real. And now I know it’s real.”

Contact Rachel Crosby at rcrosby@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3801. Follow @rachelacrosby on Twitter. Contact Arthur Kane at akane@reviewjournal.com. Follow @ArthurMKane on Twitter.

Review-Journal reporters fanned out across the valley Tuesday to gauge the situation at urgent care clinics and hospital emergency rooms. Staff writers Julie Wootton-Greener, Bailey Schulz, Al Mancini, Jason Bracelin, David Ferrara, Rory Appleton, Blake Apgar, Shea Johnson, Katelyn Newberg, Aleks Appleton, Alexis Ford, Mya Constantino and Mick Akers contributed to this story.