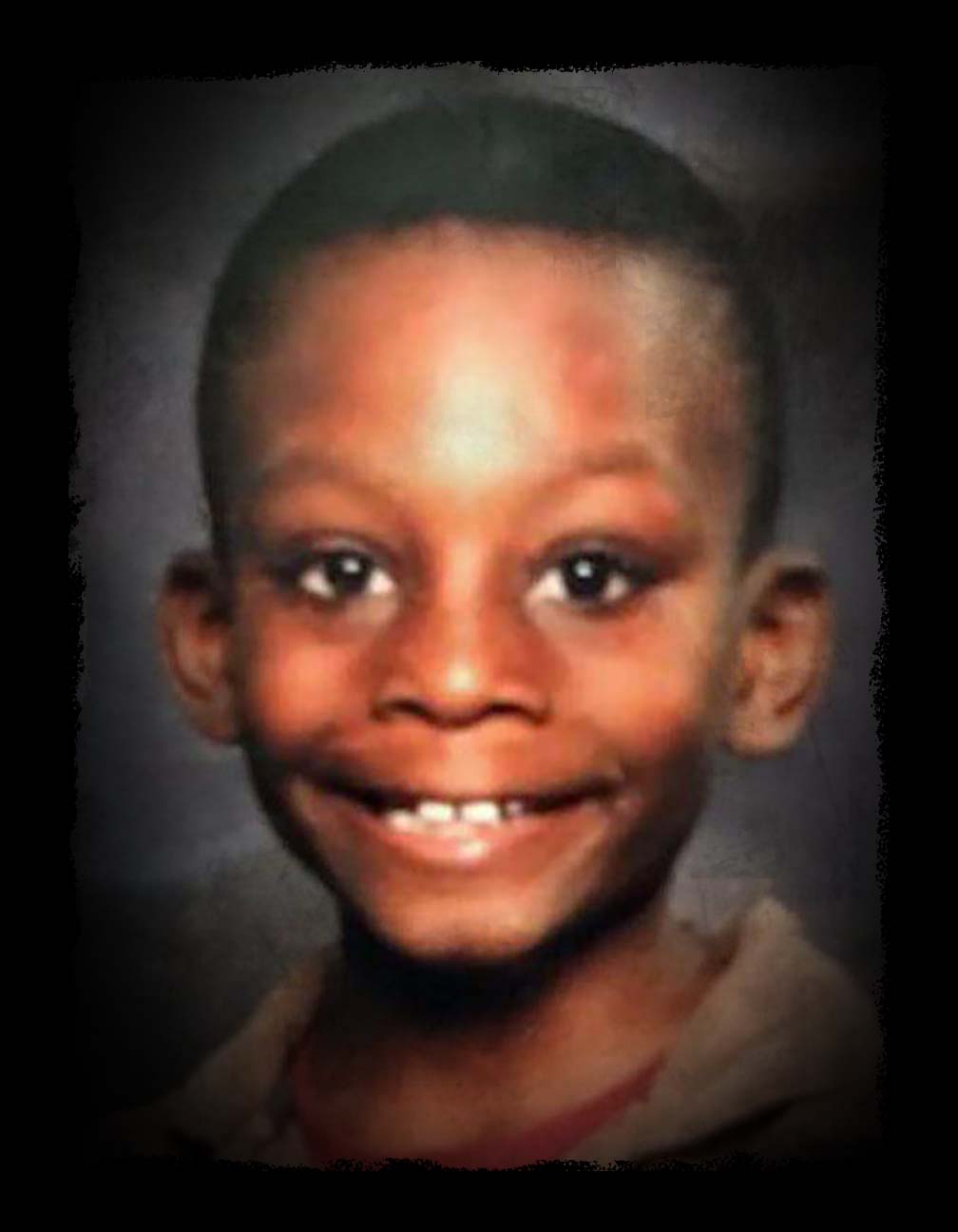

By the time anyone really searched for Aaron Jones, he had been dead for months.

The 13-year-old’s body was found in late April 2017 wrapped in a blanket under a tarp and a pile of rocks in a desolate desert lot behind a weekly motel. Aaron had been missing since January.

A grand jury indicted his father and stepmother on murder charges following testimony that the boy suffered horrific abuse from the adults who were supposed to protect him.

Confidential Clark County records that track child protection contacts with families, obtained by the Las Vegas Review-Journal, vividly document a decade of chaotic home life for Aaron and his siblings with seemingly unfit parents.

Aaron’s care was so concerning that educators at his school warned that his home life was “a recipe for disaster.”

His mother, Dijonay Thomas, was said to have deteriorating mental health and cognitive abilities, repeatedly losing track of her children. His father, Paul Jones, pleaded guilty to child abuse before gaining custody of Aaron and his sister, records show.

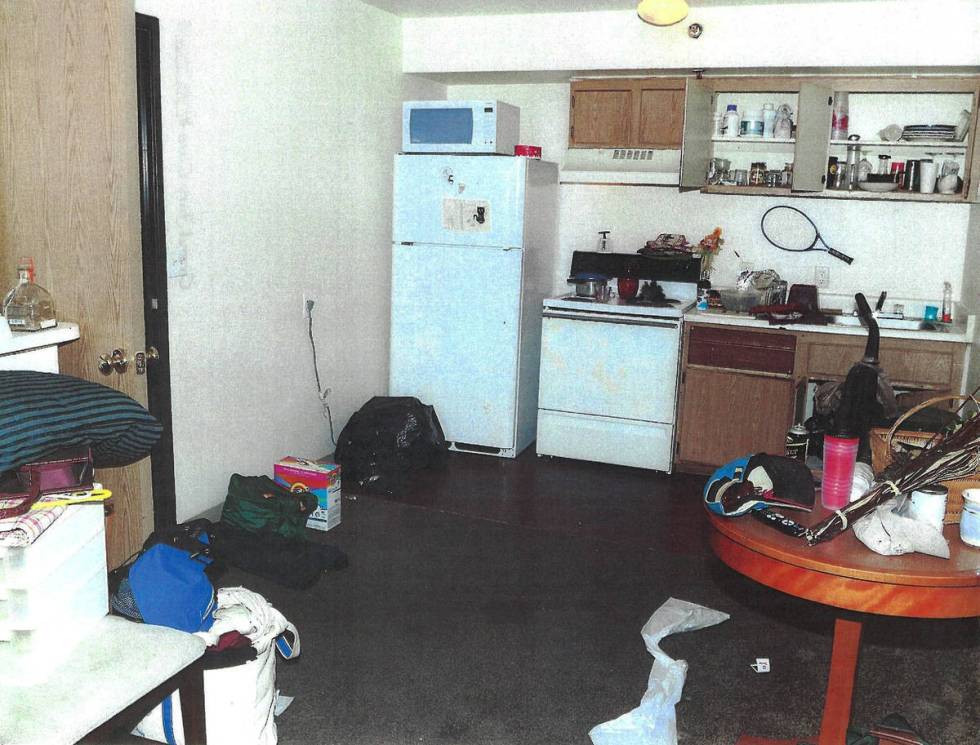

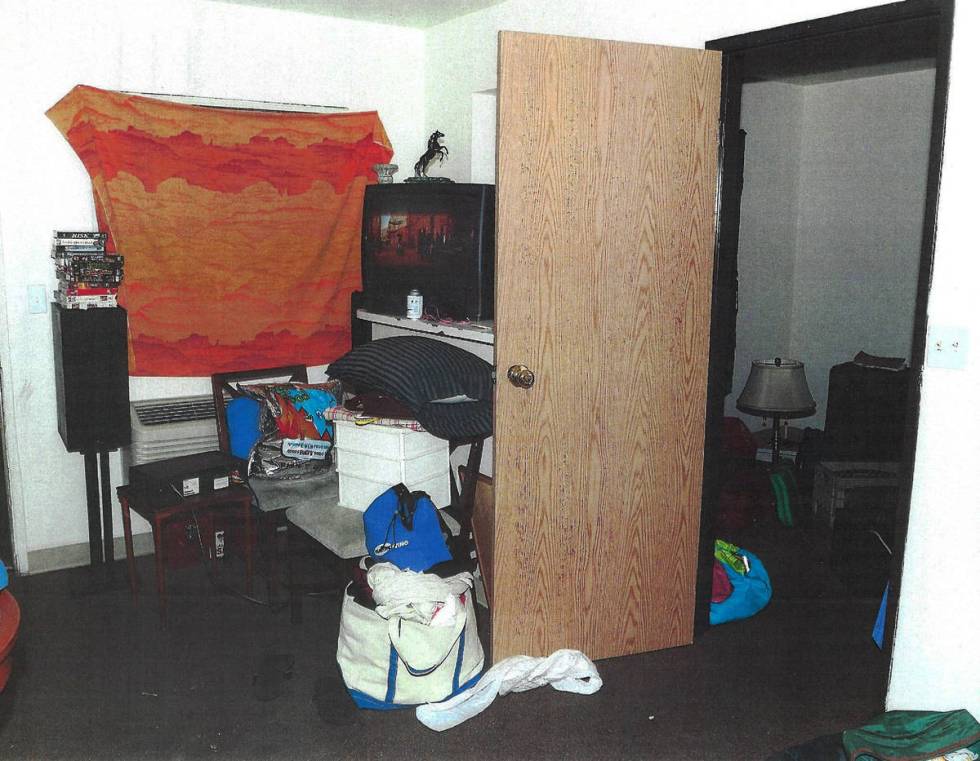

Jones and his wife, Latoya Williams-Miley, then both 33 years old, lived with 13 children in a one-bedroom Siegel Suites on a seedy part of Boulder Highway filled with transient motels, locals casinos and car dealerships.

The county UNITY records reveal child protection workers had contact with the family about 100 times, but failed to act on warnings about their home life, and made inexplicable and inconsistent decisions in their attempts to protect the youngster.

The final action that sealed Aaron Jones’ fate was a court officer who gave custody of the boy to an abusive father in June 2016, records show.

“In this case, as an entire state, we failed Aaron and should have provided him with more resources,” said Jared Busker, interim director at the Children’s Advocacy Alliance, a nonprofit that advocates for changes to protect abused children. “Our caseworkers need more time with families to make a better informed decision.”

Aaron is just one of dozens of children in the past eight years who died or were severely injured at the hands of abusive caregivers despite Child Protective Services investigations of their families, raising questions about whether recent attempts at reforming human services agencies in Nevada have worked. Child advocates also are concerned the coronavirus crisis is preventing CPS from finding abuse by stressed caregivers as children do not attend schools where abuse might be discovered.

County spokesman Dan Kulin said CPS officials by law cannot comment on a specific case, but said the county’s goal is to keep families together whenever possible.

“We are constantly looking for ways to improve and have made changes over the years to improve how we work with families to keep children safe,” he said in an email statement.

School warning

Two years before Aaron’s body was found, Ryan Lewis, then principal at Ollie Detwiler Elementary School, called CPS with a warning.

The educators told a worker that Aaron and his sister did not get along with other children, and their mother, Dijonay, exhibited bizarre and immature behavior, such as discussing a sexually transmitted disease she contracted with school staff, according to the UNITY records.

School officials described the situation as “a recipe for disaster,” records show.

Instead of heeding the educators’ warning, a social worker found the children “dressed appropriately,” “talkative” and “well mannered,” after visiting the children at school in March 2015, records show.

Lewis told the Review-Journal that CPS should take reports from school officials very seriously as they are trained at spotting problems and required by law to report suspected neglect and abuse.

“Reported cases from professionals should be taken with a different sense of urgency,” said Lewis, who has since moved to Edith Garehime Elementary. He also said county workers should update school staff on what they found after complaints so teachers can monitor the children, but that rarely happens.

It took a year after the school officials’ warning for Thomas to lose custody of Aaron and three of his siblings.

But instead of finding a foster home, officials placed Aaron and his sister with Jones, their biological father, who received a suspended jail sentence and was on probation after pleading guilty in 2015 to abusing two other children under his care, court records show.

Once Aaron was in Paul Jones’ custody, the father repeatedly punched Aaron, forced him to stand for days in a corner of an apartment soaked in his own urine and feces, withheld food and encouraged his siblings to hit him while Williams-Miley threw canned goods at the boy, according to testimony in front of a 2017 grand jury looking into Aaron’s death.

Eighth Judicial District Hearing Master David Gibson, Jr., who gave Paul Jones custody, said his hands were tied by state laws despite his ambivalence about placing the children with an abusive parent.

”In hindsight it’s easy to look at this and for anybody looking at this, it’s a tragic case of abuse and neglect,” Gibson said, whose family court position was to rule on custody and child safety issues. “The abuse and neglect law is not adequate to protect every single child. There are situations beyond anyone’s control.”

"The abuse and neglect law is not adequate to protect every single child. There are situations beyond anyone’s control."

CPS cases

Aaron’s case is just one of dozens of child deaths each year in Clark County that might have been prevented by CPS staff.

Between 2012 and 2019, about 180 of the roughly 1,000 children under 18 who died under suspicious circumstances or were seriously injured in Clark County had prior contact with CPS staff, a Review-Journal analysis of coroner and CPS records shows.

More than a third of the nearly 70 children 13 years and younger who died in homicides had CPS investigations of their family prior to their deaths, records show.

While detailed records like the ones the Review-Journal obtained about Aaron Jones remain confidential in those other cases, it is clear many died after they were left with their caregivers.

[ How to report abuse or neglect of children in Nevada ]

Busker said officials should spend more money to protect abused children. “Generally as a state, we need to do better,” he said. “One child dying is one too many.”

Kulin said the county is working to find more families who abuse their children.

“The high number of cases in which we have not had prior contact with the family is concerning,” the statement said. “We know that the most tragic cases of abuse and neglect typically occur in households in which abuse or neglect occur with some regularity. This is why it is important for the department to connect with families in crisis as soon as possible.”

Decade of neglect

Dijonay Thomas’s family came to the attention of CPS in 2006 when there was an allegation that she had burned Aaron, UNITY records show. Child protection workers could not find any marks on the boy.

At the time, Aaron was eager to go to preschool, showing off his new clothes and haircut to CPS staff, the UNITY notes say. He liked animals, displaying a pet turtle for visitors and making animal noises to get attention from CPS workers.

A year after the burn allegation, Dijonay gave birth to her third child who she couldn’t properly feed, records show. The child was taken into protective custody in June 2007 after she only fed him two ounces of formula a day instead of four.

After removing the infant in 2007, workers made about two dozen visits to the family — only about half of which were unannounced. Eighth Judicial District Family Court substantiated neglect in the formula feeding case, but in December 2008 gave the baby back to Thomas and closed the case.

The hearing master referred to in records only as Sullivan “told Dijonay that she was a wonderful mother and to keep up the good work,” the records show.

Dijonay saw a psychiatrist at CPS’s request and he determined that she does “possess, under certain circumstance, the capacity to safely and effectively parent her children,” records show.

More than four years went by with no complaints or entries in the UNITY record.

In 2013, North Las Vegas police called CPS after Aaron’s sister reported that she was hit with an extension cord and her brother was threatened with a knife by Thomas’ boyfriend. Aaron, just days after his 10th birthday, told CPS that his sister, who was two years younger, had lied because she didn’t like her mother’s boyfriend, records show. The allegation was found to be unsubstantiated, but county officials noted concerns about Dijonay’s care of her growing family.

“(M)other appears to be low functioning and may have issues regarding age appropriate behaviors,” CPS workers wrote, adding the mother brought the daughter to elementary school wearing high heels and lipstick.

At that point, Aaron was the oldest child in the family and he prided himself on trying to help raise his siblings, including cooking rudimentary meals and looking after younger children, workers wrote in UNITY notes.

Unsubstantiated neglect

Several times CPS workers determined that credible neglect allegations were unsubstantiated, even after police documented that Dijonay lost track of her kids.

In 2014, one of the children escaped the family apartment while Thomas was in the shower. He stole a golf cart and crashed it into a parked SUV. CPS closed the case, determining there was no neglect and the children were safe.

The following year in November 2015, one of Aaron’s brothers fled from the family during a trip to a shopping mall on Charleston Boulevard and was found by police, who noted that the 8-year-old urinated in the squad car and the mother didn’t seem concerned.

“Upon locating the mother there was concern of her aloofness about the situation and ability to communicate as the officer suspected that she may be drunk,” a CPS worker wrote.

Workers also found that one of the children hadn’t been to school in nearly a month. Thomas is quoted in the UNITY records saying the children don’t go to school because they don’t want to go.

In all, four allegations of inadequate supervision against the family were unsubstantiated, according to a Jan. 23, 2016, entry in the UNITY records.

Thomas and her attorney, who has since been disbarred according to the Nevada Bar Association website, could not be reached for comment.

The family lived in a number of apartments and weekly motels around Las Vegas and North Las Vegas, being “evicted several times due to the children’s behaviors,” records show.

In March 2016, Dijonay told CPS the family moved in with a relative, but the address provided to the agency did not exist.

“There is no present danger identified at this time because the family’s whereabouts are unknown at this time,” the UNITY notes say.

Missing families

Aaron’s case is not unique. The Review-Journal identified at least five cases where CPS workers lost track of the families before a child died or was seriously injured, coroner data and child death disclosures show.

For example, in August 2018, 3-year-old Dejan Hunt was found dead in a duffel bag and police reports say her mother admitted to biting and hitting her before her death. State child welfare disclosures say that about a year before Dejan’s body was found, CPS received an allegation of abuse and neglect about the family.

“Due to unsuccessful attempts to make contact with the family and insufficient information available to support the allegations, the allegations were unsubstantiated and the case closed,” the report said.

State policies are part of the problem.

In Nevada, CPS workers can close a case as unable to locate if they can’t find a family after four attempts. An unable to locate determination automatically records the abuse or neglect allegations as unsubstantiated, so no further investigation is done.

In contrast, Los Angeles County workers must continue to search for the family and mark the allegation “inconclusive,” leaving open the possibility the abuse or neglect happened, county policy records show.

Three-year fight for child autopsy records

For three years, the Las Vegas Review-Journal has been battling to force the Clark County Coroner to release autopsies of children who died in suspected child abuse cases. The information is key to determining whether the deaths could have been prevented.

In 2017, a district court judge ruled that there is no exemption in state law that allows the coroner to withhold autopsies. The county appealed, spending more than $80,000 in taxpayer money to take the case to the state Supreme Court.

The county argued that laws preventing access to child death review records and a nearly 40-year-old state Attorney General’s opinion makes the records private.

In February, the Supreme Court ruled autopsies are public record but allowed the coroner to redact “sensitive, private information.” The case was sent back to the lower court to determine what information could be redacted and the next hearing is scheduled for September.

Children removed

When CPS caught up with the family, the CPS worker and a supervisor finally substantiated an inadequate supervision allegation against Dijonay in the UNITY file, records show. One of the children had escaped from the family’s apartment at 4 a.m.

CPS put together a safety plan for the mother and grandmother, Pia Coleman, but the family did not follow the plan, UNITY records show.

On April 19, 2016, workers decided that the children were under impending danger and had them moved to Child Haven, the county’s child protection facility.

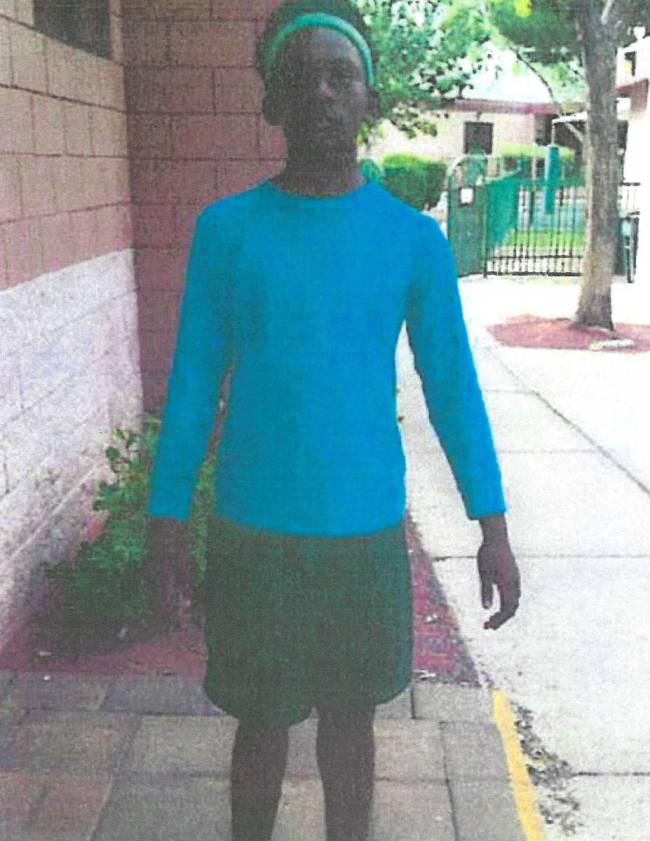

Now 13, Aaron was apparently having a tough time at Child Haven, the UNITY records show. He often picked fights and provoked other children – physically attacking or arguing with other youths at the county facility at least four times.

Six days after CPS removed the children, Aaron’s father, Paul Jones, told CPS workers that he wanted Aaron and his sister. The records, which end in May 2016, do not describe how Jones found out that Dijonay lost custody.

Jones was still on probation after pleading guilty to child abuse, neglect or endangerment in response to charges he hit his 14-year-old and 3-year-old children with a cable, court records show. But he told CPS workers that he completed all the requirements in his child abuse case and that it shouldn’t impact his ability to care for Aaron and his sister, UNITY records show.

CPS workers allowed Jones to see the children. “CPS agreed to set up visits for the father on campus for Monday and Wednesday from 4:30 pm - 5:00 pm,” UNITY notes show.

Gibson, who has since been appointed a judge, was initially not on board with Paul Jones taking Aaron and his sister.

“Paul Jones expressed that he was interested in getting custody of his children but the DA pointed out that Mr. Jones has a criminal conviction of child abuse and neglect,” UNITY notes say. “Hearing Master (David) Gibson informed (Jones) that wouldn’t be a possibility.”

Gibson said despite his initial refusal to grant custody, the father has rights to the children even with the child abuse conviction because Aaron and his sister were not the ones abused in the 2015 criminal case.

“He had very good representation from the public defenders office,” Gibson said. “The DA’s office was not able to contest it on legal grounds. The court’s hands were tied based on the law even as I had personal reservations. I have to apply the law based on the facts in front of me.”

Abusive home

On June 8, 2016, Paul Jones obtained custody of Aaron and his sister. In November, the parents and 13 children moved into the Siegel Suites, the arrest report in Aaron’s murder says.

Gibson said he and the lawyers from both sides were not aware that 15 people were living in a 900-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment. The records do not say if CPS visited the motel, and Gibson declined to say the county should have done more.

“I can’t comment on dropping of balls and who did what,” he said. “I can comment on that as the judge, I made the decision to place Aaron with Paul. I wish I had better information in front of me.”

In Clark County grand jury testimony, Aaron’s stepsister, Destany Williams, then 16, said she witnessed Aaron made to stand in a corner without being fed or allowed to use the bathroom, causing him to urinate and defecate on himself.

Destany testified how Paul Jones directed the other children to hit Aaron while Williams-Miley threw dog food and bean cans at him.

“It was more like Paul was hyping them up, like oh yeah, you should hit him because he did this and he did that,” Destany told the grand jury.

The abuse often started when Jones accused Aaron of stealing food and would go on for days with Paul Jones pouring water on Aaron to keep him awake, grand jury testimony said.

Jones criminal defense attorney Tony Abbatangelo said his client, who remains in jail awaiting trial, is not guilty of the charges. “I would have no comment except to say we will keep moving forward the best way we can on some very serious charges,” he said. “Paul is denying any involvement in it.” The defense did not present evidence to the grand jury.

Aaron’s stepmother, Williams-Miley, was sentenced to 10 to 25 years after taking a second-degree murder plea in June 2019, court records show.

Aaron dies

In the winter of 2016-2017, Paul shoved Aaron into a wall in the apartment, but this time Aaron did not get up, according to grand jury transcripts. Jones and Williams-Miley carried Aaron into the shower but could not revive him, Destany testified.

Later that night, Paul Jones went to take out the trash. He told the children Aaron had run away.

The exact date Aaron died is unknown.

Police reports, county disclosures and grand jury testimony note family members stated dates between December 2016 and February 2017 for Aaron’s disappearance.

In mid-April 2017, there is a notation in a public CPS disclosure that one of the children was missing and possibly ran away.

County workers marked that allegation as “information only,” which doesn’t require a CPS investigation or any further action. It was referred to missing persons.

Around that time, Aaron’s grandmother and her cousins started searching for the boy.

Grandmother Pia Coleman picked up Aaron’s sister after school and the sister told Coleman where the family lived when Aaron disappeared. “We went there to pass out fliers,” Coleman, who couldn’t be reached for comment, told the grand jury.

On April 25, 2017, Coleman’s cousins, who were also handing out fliers, started searching a fenced desert lot behind the Siegel Suites and found a pile of rocks with a blanket underneath.

“That’s when we stumble upon the body,” cousin Deante Magee, who couldn’t be reached for comment, told the grand jury.

That same day, police arrested Paul Jones and Williams-Miley.

Contact Arthur Kane at akane@reviewjournal.com. Follow @ArthurMKane on Twitter. Kane is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing.