Nevada officials tight-lipped about where COVID-19 spreads fastest

In March, Washington state disease investigators determined that a church choir practice had sickened more than 50 attendees, an early example in the pandemic of a “superspreading” event for the novel coronavirus.

Last week, undergraduate classes at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shifted to online learning after the discovery of COVID-19 case clusters at residence halls and a fraternity house.

But in Southern Nevada, state and local health officials have yet to publicly identify any specific spreading events or case clusters beyond those at nursing homes and other state-licensed facilities.

Even as state leaders employ what they describe as a targeted approach to curbing COVID-19 based on data, they have not identified specific businesses, events or gatherings as possible exposure sites for the largest numbers of people. Nor have they made public data on casino resorts, the main driver of the state’s economy, which are frequently identified as possible exposure sites.

Meanwhile, the number of new cases in the state surged in June and July after so-called “nonessential” businesses reopened.

Absent such specifics, Southern Nevada residents and visitors lack clear direction for adjusting their behaviors to slow the spread of COVID-19, said professor Samuel Scarpino, head of Northeastern University’s Emergent Epidemics Lab. For an international tourist destination like the Las Vegas Strip, the repercussions could reach beyond Nevada’s borders.

“COVID really is heavily reliant on superspreading events for sustained transmission,” Scarpino said.

“Part of the magic of Las Vegas is it brings in people from all over the world, from all over the United States, from all walks of life into one city,” he continued. “And as a result of that, you have this incredible economic fuel that powers the city. But you also have the fuel for superspreader events for COVID-19 to hop from Los Angeles to New York City.”

‘Backyard barbecues’

In late June, state health official Julia Peek said at a news conference that based on a two-week survey of newly diagnosed cases, 11 percent of infected people said they’d been to a mass gathering and 12 percent had attended a civic activist event.

“So that’s something that will be part of our normal screening and hopefully can provide more updates,” said Peek, a deputy administrator at the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services.

On Friday, Peek said that the survey had also asked whether individuals had been to a gaming resort. Those findings, however, were not disclosed.

In the weeks following that June news conference, information made public became more general, not more specific. State officials have generally referenced “backyard barbecues” and “family gatherings” as primary causes of new infections.

A presentation to the state’s COVID-19 mitigation task force on Thursday expanded slightly on this, highlighting that resorts, hotels, food establishments and health care settings are “ongoing themes related to case investigation and contact tracing.” The presentation did not name any specific locations or include other particulars.

“If the state is not providing that information, the real question to ask is why,” Scarpino said. “Are they not providing it because they don’t have it? That is a big concern. Are they not providing it because they don’t want to share it? That’s also a big concern.”

In an interview Friday, Caleb Cage, who is directing the state’s COVID-19 response, and Peek said that the state was analyzing county-level data on disease transmission to identify types of businesses and specific locations that are most frequently identified as possible exposure sites. As of this month, the officials said, that analysis has been provided on a weekly basis to county health departments to assist with their public health response.

State officials declined to provide copies of the analyses to the Review-Journal, instead referring reporters to individual health districts for the information. Health district officials did not immediately respond to a request for the documents sent Friday.

Southern Nevada Health District spokeswoman Stephanie Bethel wrote in an email Thursday that the agency was “not able to provide details regarding clusters of COVID-19 infections.”

That’s because the health district has prioritized identifying an infected person’s close contacts, not where they may have caught the disease, “because people who are recently infected are the most likely to spread the virus even if they are asymptomatic,” she said. About 11,000 of the state’s more than 65,000 cases had been identified because of contact tracing, state officials said Friday.

“Given the transmission route for this infection, there are likely to be many clusters,” Bethel wrote. “While we are making an effort to track specific locations, it is difficult to draw any conclusions because our data sets are incomplete.”

UNLV epidemiologist Brian Labus said that under the best of circumstances, identifying case clusters is complicated. For example, the mere fact that a number of newly diagnosed patients work at the same location does not necessarily mean they contracted COVID-19 at their workplace.

What if one casino had 100 employees who tested positive?

“Well, that could be from their daily lives, that could have been over a couple week period, they could have had one event for everybody that caused it, or it could be unrelated to work,” said Labus, a member of the governor’s medical advisory team. “But without a very detailed, very lengthy investigation, it’s impossible to say they all got it from this exact type of exposure or even at the casino.”

Even with the state pumping more than $100 million into investigations and contact tracing, Nevada’s low per capita public health funding makes this sort of intensive investigation less likely, he said.

The state doesn’t have “a lot of people that are working as epidemiologists and biostatisticians and disease investigators,” Labus said.

The casino question

State officials on Friday would not reveal which casino resorts are most frequently appearing in their analyses of possible exposure sites. Although the state is sharing the data with other government agencies, none of the agencies are divulging details to the public.

Cage said that casinos and other businesses identified needed to be given their “due process.” The state’s findings are reported to regulatory agencies such as the Nevada Gaming Control Board, which is tasked with enforcing new health measures related to COVID-19 at casinos, he said.

But Michael Lawton, a spokesman for the control board, said in an Aug. 11 email that the regulator “does not receive or track COVID information at casinos.” Health district officials also said this month that they couldn’t provide the number of casino resort employees who have tested positive.

Casinos have the potential to be major exposure sites, said professor Linsey Marr, an airborne disease expert at Virginia Tech.

Studies have shown that COVID-19 transmission is far more likely to occur indoors because of the lack of air flow. In a worst-case scenario, one person with the disease could infect hundreds of others inside some of the most popular Las Vegas casino resorts, Marr said.

“At the right time of day, it’s uncrowded, and I would be comfortable if everyone walking through a casino were wearing masks,” she said. “But once it gets crowded, that’s a much riskier situation.”

Nevada’s casinos are taking precautions to reduce risk.

They must screen hotel guests’ temperatures, require that guests and employees wear facial masks and limit gaming area occupancy to allow for social distancing, among other requirements. However, at least seven Nevada gaming properties are facing complaints that they have not properly enforced health and safety directives.

Cage gave a general answer when asked what state officials had concluded about the danger of transmission at casino resorts.

“Whether it’s a grocery store or a resort or any of the other places that people gather, then we have the potential for spread of the virus,” he said.

But Las Vegas’ world-renowned casino resorts are unlike most other businesses because of their clientele, namely tourists, Marr said.

More than 1 million visitors came to Las Vegas in June, according to official tourism data. Over one weekend in mid-July, about 26,000 smartphones that were on the Strip traveled to every mainland U.S. state except Maine within four days, according to an analysis of device data published this month by ProPublica.

Any one of those visitors could bring the disease home and reintroduce it into their community, Scarpino said. However, tracking the spread of the disease caused by the new coronavirus from one state to another is difficult.

According to the most recent state data, released on July 25, Nevada officials report knowing of only 10 out-of-state visitors who tested positive after returning home since casinos began reopening in June. That may seem like good news, but Scarpino said it likely reflects an “antiquated” interstate disease reporting system.

“My hunch would be that those numbers are low because of reporting issues, not because they’re actually low,” he said.

‘Undifferentiated generalizations’

Questions also have been raised about the data used to support decisions to keep some businesses closed in Nevada.

In July, Gov. Steve Sisolak closed bars in several counties to slow the spread of COVID-19. Those counties had been deemed to have an “elevated disease transmission risk” based on their testing capacity, positivity rate and number of new infections.

At the state task force meeting Thursday, Washoe County health officials requested that their bars be allowed to reopen. In response, Dr. Christopher Lake of the Nevada Hospital Association asked whether state officials could estimate how many COVID-19 cases had been linked to restaurants in the county allowed to remain open.

Cage responded that it should be possible to calculate that. In an interview Friday, he declined to answer whether Nevada exposure data had been evaluated before closure of the bars, citing a lawsuit filed by dozens of the businesses in Clark County.

An attorney representing the bars expressed skepticism.

“That evidence just did not exist because we would have seen it in that case if it did,” Las Vegas attorney Dennis Kennedy said. “You just have these undifferentiated generalizations. If you’re closing business down and putting thousands of people out of work, you ought to have more than that.”

Peek said the state is improving its analysis of COVID-19 disease transmission trends.

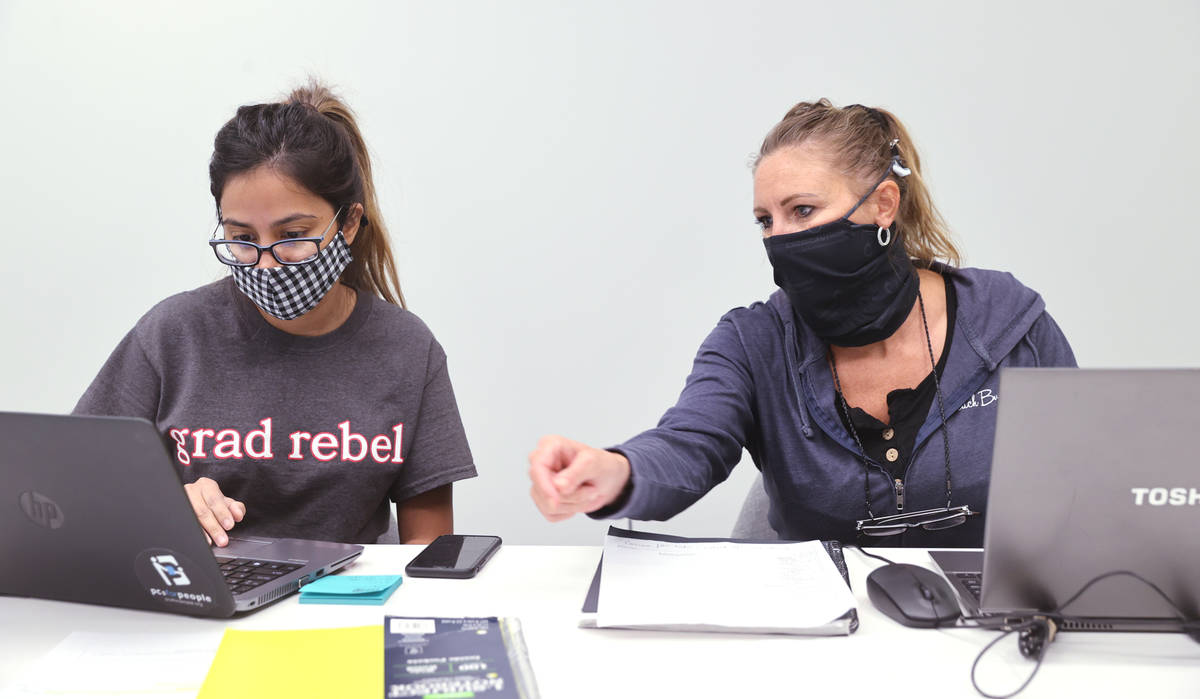

Officials have created a uniform 65-question survey for all Nevada disease investigators, including questions about whether an infected person works in a casino or hotel and where they believe they were exposed to the coronavirus. Some disease investigators will begin using the survey next week, and it should be used statewide by mid-September, Peek said.

By ensuring everyone is asking the same questions and by storing the collected information into a single database, the state’s task force should soon be able to share trends on a weekly basis with the public, Peek said.

How specific the shared information will be remains to be seen. For it to be most effective, Scarpino said, officials should release the most detailed information they can without violating patients’ privacy. A better-informed public, he said, can make more educated decisions about where they go and what they do.

“I think that by not having the information public, we prevent ourselves from doing that,” he said.

^

Contact Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Follow @davidsonlvrj on Twitter. Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.