After the bodies have been taken and the ambulances speed off, Officer Andy Navarro weaves the pieces together.

The fatal traffic investigator threads a grid of the destruction with different colored cones. He scrutinizes the cars’ paths, carefully retracing each inch. Who hit their brakes, who didn’t, where they collided.

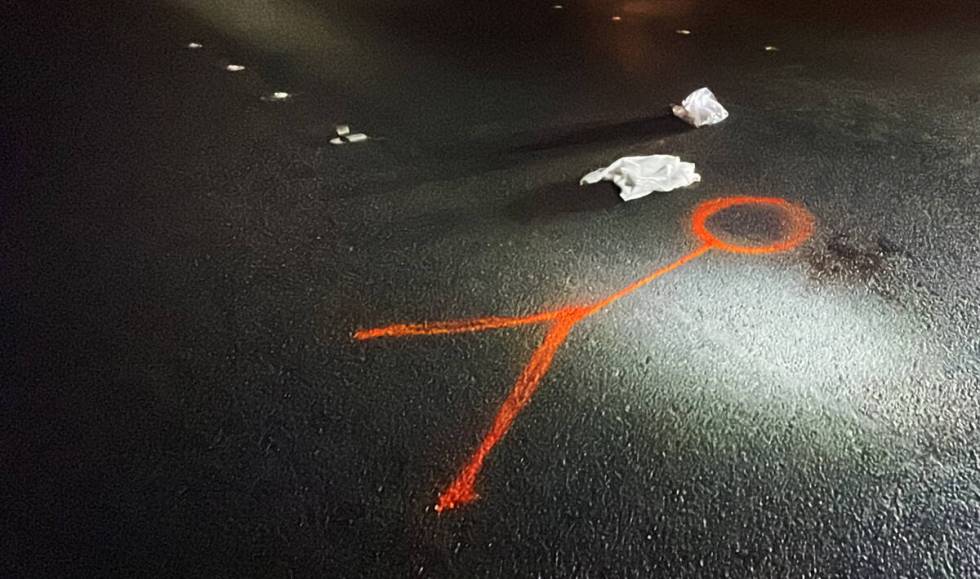

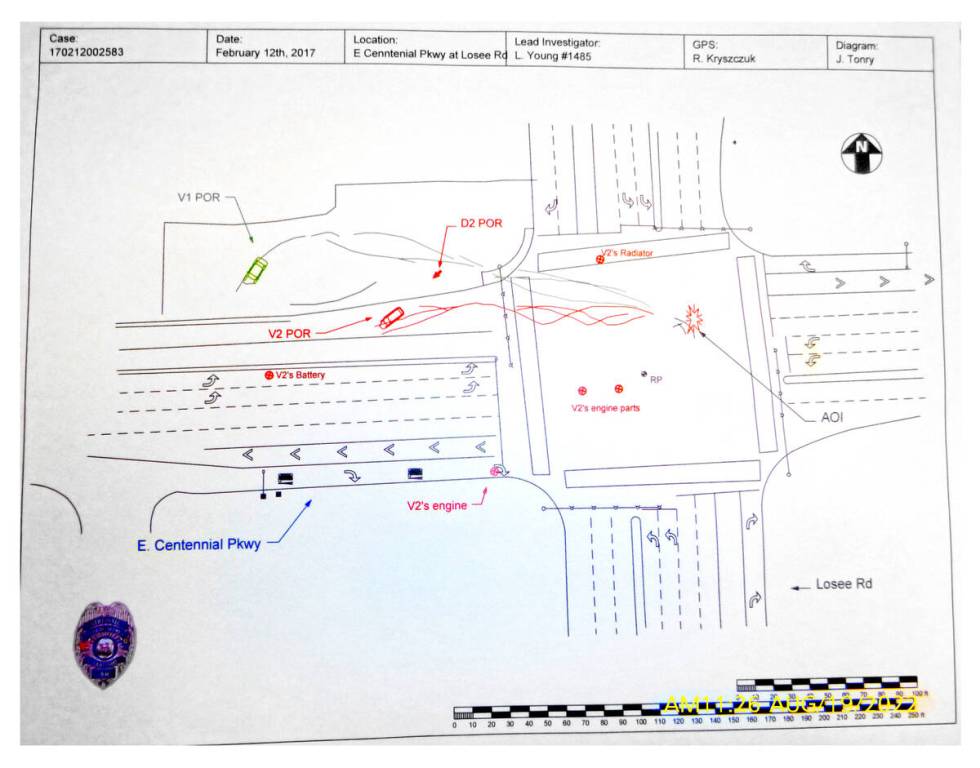

Spray paint outlines each piece of evidence on the asphalt. Two cameras rapidly rotate in unison, capturing a panoramic view of the scene, which is later traced and printed onto paper.

Navarro and his colleagues at the North Las Vegas Police Department did the same painstaking work earlier this year at the deadliest crash the state has seen in 30 years.

In a matter of seconds, a speeding driver ran a red light, wiping out seven members of a family and killing himself and his passenger.

“It looked like a war zone,” said Navarro, whose unit has been stretched thin by turnover and retirements. “The mind is not designed to see that kind of carnage.”

That tragic crash and a recent uptick in traffic fatalities have made public safety officials keenly aware they are falling behind.

The city’s police force has remained virtually stagnant in size over the past decade, while its population has grown some 50,000 residents. Of its 283 uniformed officers, only a dozen work full-time in the department’s traffic unit, a spokesman said. Half are trained fatal investigators.

Agencies valley-wide collaborate to catch risky drivers. But they also want to beef up their squads, while facing the nationwide challenge of recruiting and retaining officers.

“All the divisions in our police department end up just being strained,” said Lt. Christopher Cannon, who heads North Las Vegas traffic officers. “The ripple effects are just huge.”

Turnover is costly

Navarro responds to as many as 350 collisions a year. Some inevitably end in death.

Thirteen people died on the city’s roads in 2021. This year has been far worse.

There have been 19 fatal crashes in North Las Vegas through July, killing 28 people. It’s the deadliest year since 2016, when 20 collisions killed 23 people.

Members of Navarro’s unit have their hands full. They are the city’s front-line defense, both investigating and preventing the most dangerous driving offenses.

Cannon said the department is always “chasing at the tail” to increase its ranks as the demand for police services grows.

The force has lost 14 people to other agencies so far this year, according to the department’s union president, who called it “unheard of” in his 18 years there.

They either leave the state or choose to work for other local agencies that pay more and have additional resources, said Loran McAlister, who has represented the North Las Vegas Police Officers Association for two years.

Other departments that need additional manpower include the Metropolitan Police Department, which investigates the majority of the valley’s deadly crashes and has its own branch of detectives dedicated to investigating them.

“I think we could use more to relieve them from the amount of exposure that they have to these terrible scenes,” said Lt. Daryl Rhoads, who heads Metro’s traffic unit.

In North Las Vegas, the union is in talks with the city to provide additional incentives to officers that McAlister says will save money in the long run. He estimates the cost to train new recruits is roughly $75,000, a significant loss if the officer leaves for another job.

Police spokesman Sgt. Jeff Wall said that the department expects about 30 new officers will go through the police academy this year and that there are ongoing efforts to recruit in cities and at universities nationwide. Next year, the department is opening its third police station at the corner of West Deer Springs Way and Harwood Creek Street.

But it also takes about a year and a half to get new officers on the street. Joining the traffic unit requires even more specialized training.

“That’s a huge time delay,” McAlister said. “In that 18 months, we could have people resign, get fired or move on to other places, and then those holes aren’t going to be filled.”

A personal calling

Navarro can recall with vivid detail the first time he saw a car strike someone.

While walking to school at age 6, he watched an orange Camaro strike an elderly woman in a crosswalk and drive away. The lady stood up, grabbed her toppled groceries, and carried on.

His own life has also been directly impacted.

In 2006, he and his wife were in a T-Bone crash on Lake Mead Boulevard near Walnut Road. He only saw a flash of the speeding pickup truck before it hit them. Their Jeep rolled onto its side, and witnesses pulled them out of the vehicle’s window. Navarro needed nine staples in his head.

In the most devastating of events, his 17-year-old cousin was killed while crossing Nellis Boulevard near Flamingo Road in May 2012. Bryan Navarro had been a high school senior, working at McDonald’s to pay for prom tickets.

The driver of the Nissan Altima that hit him, Tomas Del-Angel, fled the scene and was located hours later at home. He spent two years in prison for the crime.

“It wears on you that people don’t understand the realities of their actions,” Navarro said, adding that most collisions could easily be avoided. “But it also makes you appreciate life.”

With each ticket he issues, he aims to prevent the consequences he’s seen first-hand.

North Las Vegas Police Officer Andy Navarro, a fatal traffic investigator, snaps photos of evidence at the scene of a hit-and-run crash on North Mary Dee Avenue near East Cheyenne Avenue and Civic Center Drive in North Las Vegas on March 25, 2022. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto

North Las Vegas Police Officer Andy Navarro, a fatal traffic investigator, snaps photos of evidence at the scene of a hit-and-run crash on North Mary Dee Avenue near East Cheyenne Avenue and Civic Center Drive in North Las Vegas on March 25, 2022. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto  North Las Vegas Police Officer Andy Navarro, a fatal traffic investigator, at the scene of a hit-and-run crash on North Mary Dee Avenue near East Cheyenne Avenue and Civic Center Drive in North Las Vegas on March 25, 2022. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto

North Las Vegas Police Officer Andy Navarro, a fatal traffic investigator, at the scene of a hit-and-run crash on North Mary Dee Avenue near East Cheyenne Avenue and Civic Center Drive in North Las Vegas on March 25, 2022. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto He’s there to catch the red-light runners, the reckless drivers, the drunk drivers. To stop the next fatality.

Navarro, now 37, first worked as a correctional officer at High Desert State Prison for two years before enrolling in the police academy in 2015. He transferred to traffic three years later.

He felt he could make the greatest difference there. His reports would tell exactly what happened in great detail — and find justice for other families in their time of need.

“He’s a special breed,” said Autumn Navarro, his wife of nearly 17 years and mother of their six children. “Though some of it really weighs on him.”

Navarro empathizes with each victim.

The Zacarias family killed in their minivan, headed to meet their relatives at a lunch buffet, reminded him of his own relatives.

William Alvarez, who was killed on his motorcycle commuting to work, could have been him on his department-issued bike, taking that same route home.

On the Fourth of July, he raced to respond to a fatal crash, forgoing plans to set off fireworks with his family. He thought of the 22-year-old woman who’d never see hers again.

“Those are the ones that get to you,” Navarro said. “It makes you wonder if they even had a chance to respond to it; if they even saw it coming.”

Investigation of a crash

The call came in just before 10 p.m.

It was mid-August, and Navarro had already spent a full day teaching other officers how to work a radar gun.

He was setting an alarm for an early morning when his sergeant’s name flashed on his phone. A sedan had struck a man near the intersection of Craig Road and Camino Al Norte.

Navarro pulled on a pair of jeans and his police vest and headed to the scene. By the time he arrived, the injured man had already been taken to UMC.

Witnesses said he darted between cars before crossing over the median and into the pathway of a Nissan Altima. The man’s body crushed the windshield. Glass shards showered inside the car like raindrops.

The driver, who showed no signs of impairment, said the man popped out in front of him before he could stop.

“It’s consistent,” Navarro said, illuminating the gravel with a flashlight and noting that there were no signs of emergency braking.

He began to measure the damage to the car’s windshield, hood and bumper. Those metrics, combined with the pedestrian’s height, would be used to determine the car’s approximate speed at impact.

Two of his counterparts fanned out over the scene while a crime scene investigator took pictures.

A white square of spray paint outlined the area of impact. Dotted orange lines traced the 24 feet that the pedestrian had either slid, tumbled, or rolled. A stick figure signified where he came to a rest, next to a blood stain in the road’s middle lane.

Navarro would retrieve video surveillance from Dignity Health hospital across the street, a gas station and an auto parts store.

A few days later, he went to UMC to check on the pedestrian, a man in his 20s. He had already been discharged.

Cases conclude in court

In between serious crashes, Navarro helps motorists stranded on the streets, pursues speeders and pulls over drunk drivers. He imparts advice to those he encounters, including a 16-year-old who crashed the night she got her license.

But his work typically concludes off the streets.

Earlier this month, he sauntered through security at North Las Vegas municipal court.

“Oh yeah, back again,” he told the bailiff, flashing his dimpled smile.

Today’s case was for an aggressive driving charge he cited against Luis Gonzalez, who sat on the right side of the courtroom. When it was time, North Las Vegas Municipal Court Judge Chris Lee came to the bench and asked Gonzalez if he was ready for trial.

“As ready as I’m going to be,” Gonzalez said.

Lee told him the officer was in court, ready to testify. He again read to him the plea deal city attorneys were offering: A $415 speeding ticket.

Would he take it?

Navarro, in the gallery, raised his eyebrows in concentration as he refreshed himself on the facts of the December arrest. But it wasn’t necessary after all. Gonzalez took the deal.

Navarro would still show up to court again for the next subpoena, just as confident to justify each citation or arrest.

To him, it’s a matter of saving lives. Perhaps even those of the violators.

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter.