Editor’s note: This is part two of an occasional series on evictions in the Las Vegas Valley. Read part one about Nevada’s unique eviction process.

It took Margarita DeLoach nearly three weeks to reach her breaking point last winter.

Nearly three weeks without heat in her Henderson rental home. Nearly three weeks of waiting for her landlord to fix the problem while the temperature dipped into the 40s at night. Nearly three weeks of sleeping with her four children next to the gas fireplace in the living room to keep warm.

DeLoach said the lethargic response stood in stark contrast to that June, when her landlord, one of the Las Vegas Valley’s largest renters of single-family houses, had stuck an eviction notice to her door on the first day her rent became overdue. She caught up on the money she owed King Futt’s PFM, including an additional $250 “eviction fee,” and stayed in the home.

But by mid-December 2018, DeLoach was ready to leave. She surrendered her keys and moved out two months before her $1,275-a-month lease was scheduled to end.

“It was unbearable,” said DeLoach, 45, who gave the Las Vegas Review-Journal copies of her emails with the company documenting the ordeal. “They were efficient when it came to needing their money, but when it came to them honoring their contract and fixing things they were not up to par.”

DeLoach is one of 17 current and former King Futt’s tenants the Review-Journal spoke with during a monthslong investigation into the Las Vegas Valley’s evolving single-family home rental market. Many alleged the company rented them neglected homes, put off requested repairs and over-relied on unskilled handymen.

Meanwhile, some tenants alleged, King Futt’s rushed to start eviction proceedings, kept former tenants’ security deposits and sent debt collection agencies after them — tactics that stained their credit histories and stymied their ability to find new rental housing.

The Review-Journal investigation found King Futt’s secured court-ordered evictions last year at a rate of more than 14 times per 100 single-family rentals, nearly nine times higher than the Las Vegas Valley average. In all but three of those 61 eviction cases, court records show, the company started proceedings on the first business day after a tenant’s rent was due.

King Futt’s, which deals almost exclusively in homes it purchased at foreclosure auctions during the Great Recession, was also the subject of code complaints at a rate more than double the average for single-family rental homes. As of August, the company owned, rented out and managed about 500 residential properties, including more than 400 single-family homes.

In an interview last month, King Futt’s executive manager Erin Ben-Samochan defended the company and its practices.

While she declined to talk about DeLoach’s heat problem, Ben-Samochan said King Futt’s values maintenance and has an after-hours emergency hotline and an employee dedicated to tracking requests for repairs. Tenants were responsible for most of the code complaints the company’s homes faced last year, she said.

King Futt’s makes clear that tenants must pay their rent by the fifth of each month or they could face eviction, Ben-Samochan said. And this year, she said, the company began waiting an additional week to 10 days after a tenant’s rent became overdue before starting eviction proceedings.

“We just feel like that’s our way to get our house back and get our property back with a nonpayment of rent situation,” she said. “Unfortunately, we have to still pay our loans, our mortgages, our utilities, even when tenants are not paying the rent or not paying it on time.”

The Review-Journal’s investigation found King Futt’s is far from alone.

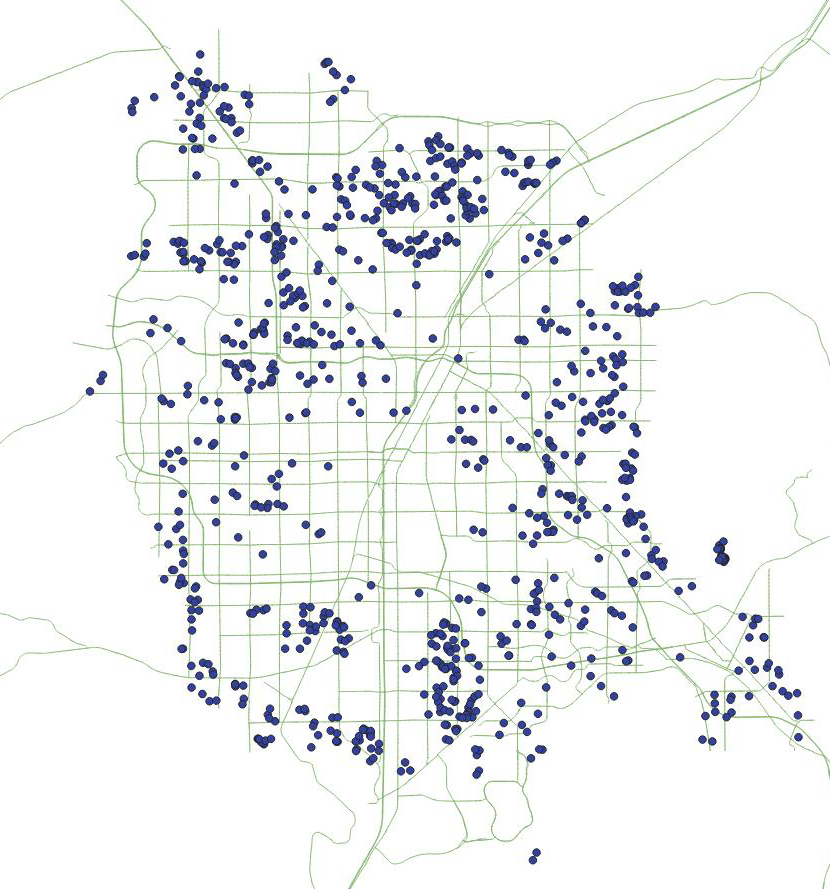

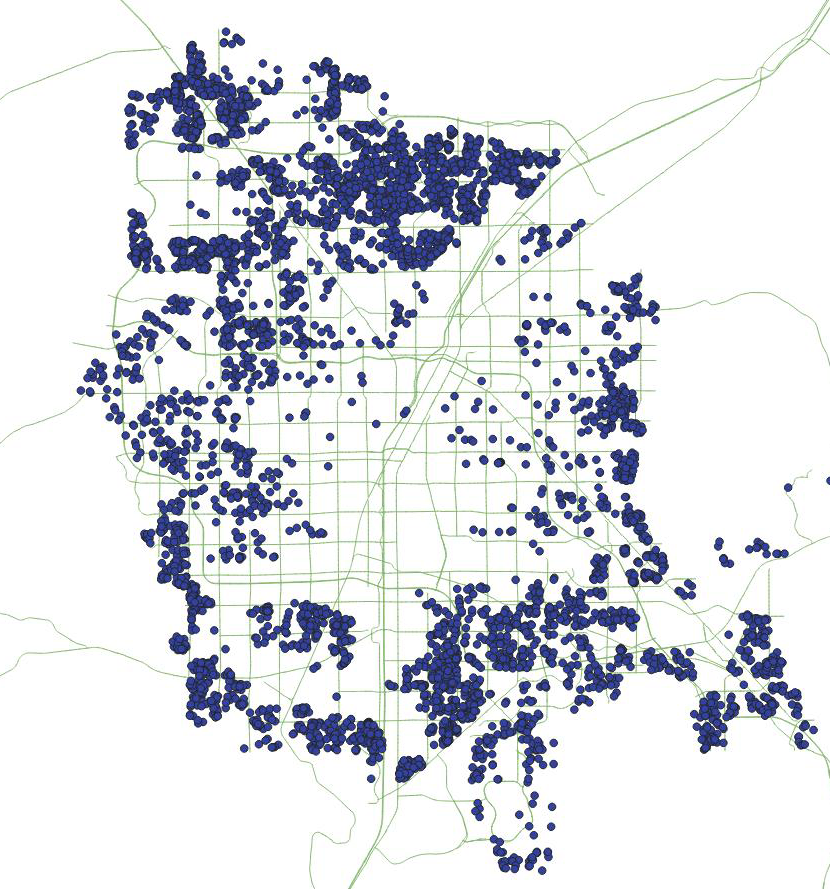

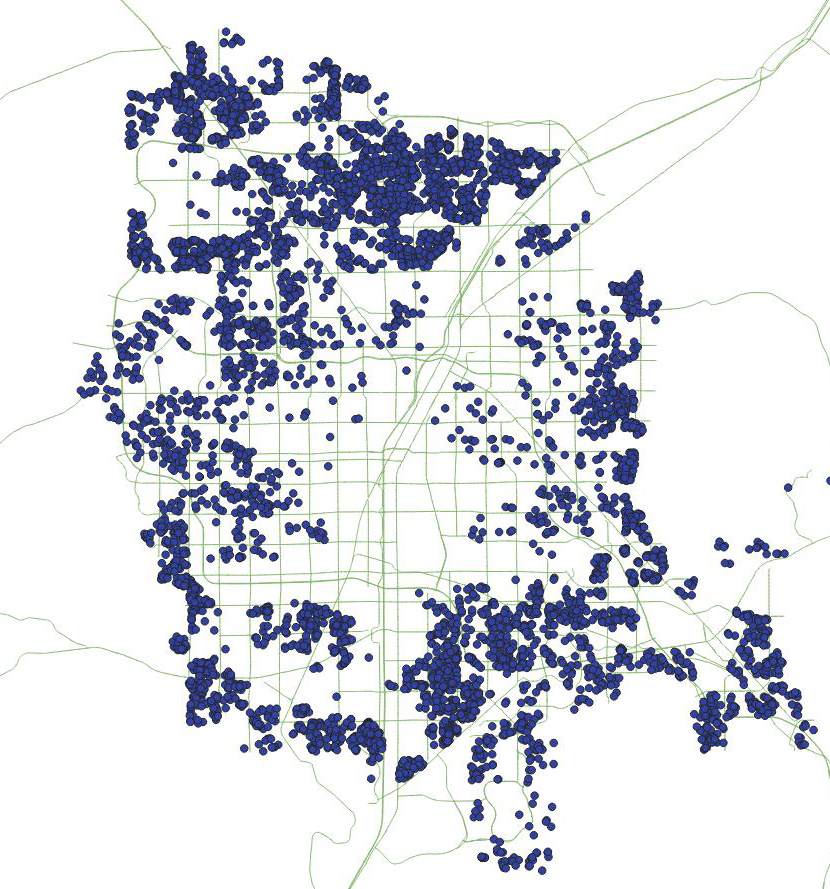

Documenting a recession-spurred shift in the single-family rental market, the newspaper found that Las Vegas Valley landlords that own 100 or more single-family homes bought during and after the 2008 financial crisis — nine companies that now own almost 8,000 houses combined — all had eviction rates last year higher than the valley average for single-family rentals.

Recession reshaped Las Vegas rental market

These companies held less than 6 percent of the single-family rental market last year but accounted for almost 18 percent of its court-ordered evictions, the investigation found. Six of the nine companies were also the subject of code complaints at higher-than-average rates, although not every complaint resulted in a violation.

But while major cities in other states are enacting laws to ensure landlords are maintaining rental homes, most local governments in Southern Nevada don’t even track which houses inside their jurisdictions are rentals, and none regularly inspect rental homes to ensure they are up to code. In North Las Vegas, the largest single-family landlords have violated city law for years by operating without business licenses.

The Review-Journal’s findings signal a need for government officials to more deeply examine whether current regulations are adequately addressing corporate homeownership, said state Sen. Yvanna Cancela, D-Las Vegas, who championed measures aimed at strengthening tenants’ rights during the 2019 legislative session.

“We want there to be an inventory of affordable single-family home rentals, but it should also be an inventory that tenants know if they call their landlords with an issue it will be resolved,” Cancela said.

Recession-created rentals

The Las Vegas Valley was the epicenter of America’s foreclosure crisis. A decade later, renters like DeLoach continue to live in the aftermath.

As families lost their homes during the recession, local and out-of-state investors like King Futt’s bought and converted the distressed suburban properties into rentals. The number of purchases made by the largest of these firms skyrocketed around 2013, after the federal government began selling foreclosed homes in bulk to Wall Street-backed rental companies armed with private equity cash.

Homeownership rates have yet to fully recover. As of 2017, renters still lived in about one of every four occupied single-family homes in the valley, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

One tenant's story

Melody Cabral and her family moved into a King Futt’s property covered in trash and the former tenants’ belongings. Since they moved in six months ago they’ve encountered multiple issues with the home.

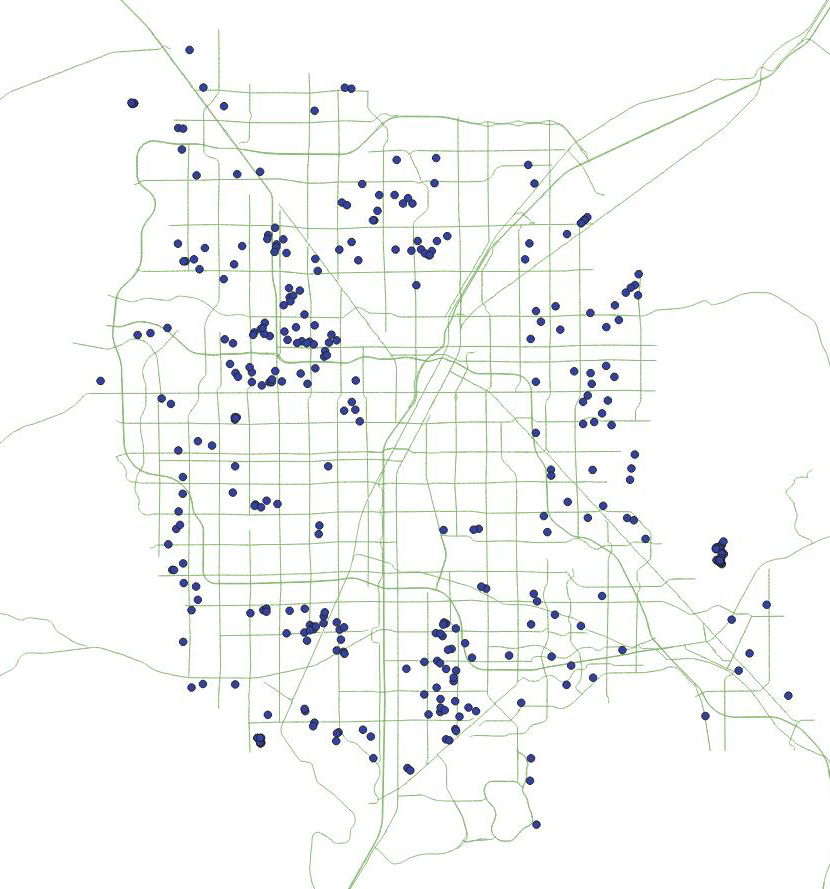

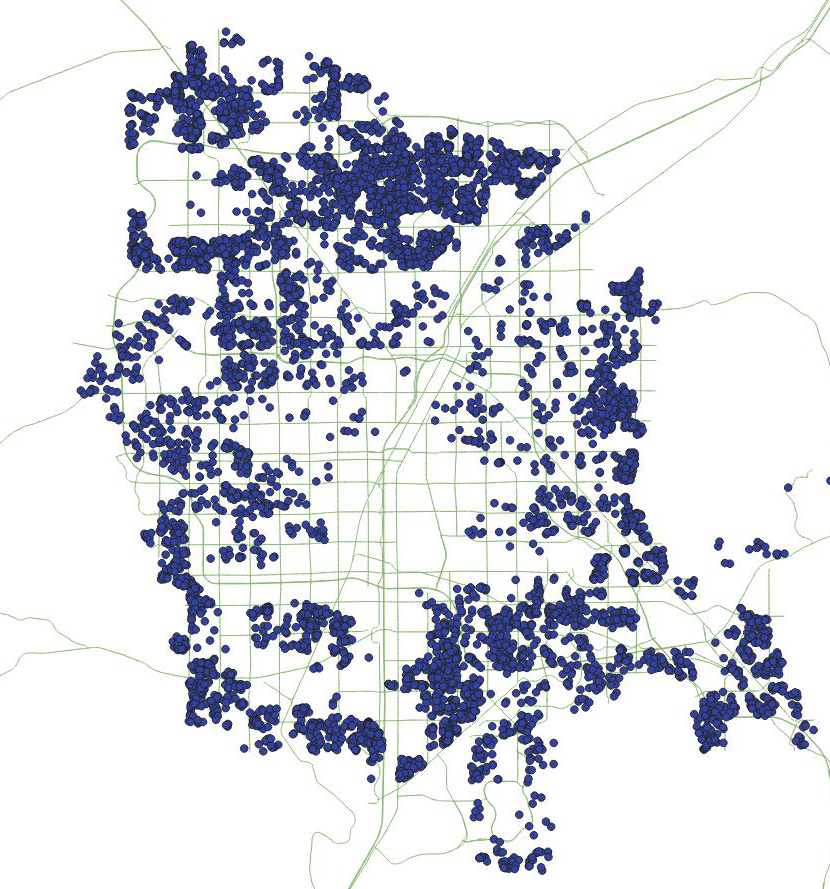

This shift has been realized in the portfolios of the valley’s largest single-family landlords, corporations whose vast holdings lie scattershot across the region’s neighborhoods.

As of this August, Texas-based Invitation Homes owned about 3,100; Arizona-based Progress Residential was nearing 1,500; and California-based American Homes 4 Rent had close to 1,000.

King Futt’s was established locally in 2008, Ben-Samochan said. By the end of 2012, property records show, the company had spent more than $54 million at foreclosure auctions to buy hundreds of single-family homes, townhouses and condominiums stretching to every corner of the Las Vegas Valley. While the company did not disclose who serves on its board, King Futt’s shares management with two local extended-stay hotels: Sportsman’s Royal Manor on Boulder Highway and Manor Suites, located south of the Strip.

Last year, King Futt’s and other recession-borne landlords evicted Las Vegas Valley tenants renting single-family homes at rates ranging from about 1.4 to 8.9 times higher than the average for single-family home rentals, according to a joint analysis of government records by the Review-Journal and Rutgers University assistant professor and researcher Eric Seymour.

Such practices are bolstered by Nevada law, which allows landlords to evict tenants in as little as 15 days and without a court hearing if they miss a rent payment. The process is one of the fastest in the nation, a Review-Journal survey published in June found.

“Large operators benefit from an economy of scale and automating their eviction processes,” said Seymour, who has studied the effect of post-recession investment on rental housing stability in Detroit. “Given the growth in the number of low-income households living paycheck-to-paycheck after the recession, there are a number of prospective tenants waiting in the wings.”

While these deep-pocketed investors were lauded for helping stabilize precarious and blighted housing markets across the U.S., some have come under national scrutiny for the ripple effect their market dominance has caused.

Last year tenants sued Invitation Homes, the nation’s largest single-family landlord, alleging the company charges exorbitant fees, skimps on maintenance and files for eviction at a startling rate. The potential class-action lawsuit was filed in a U.S. district court in California and represents tenants in 11 states, including Nevada.

Attorney Alex Tomasevic, whose San Diego-based firm filed the lawsuit, said tenants fear losing their home if they stand up against a corporate landlord that fails to live up to a lease.

“The threat of eviction hanging over their head creates that incentive to pay up or shut up,” Tomasevic said. “Largely, I always think it boils down to corporate greed. Try to spend as little money as possible. When people complain, ignore them and hope they go away.”

Invitation Homes spokeswoman Kristi DesJarlais said the company believes the lawsuit’s allegations are without merit. Invitation Homes is upfront with residents about the fees it can charge and is committed to providing quality customer service, she said. She also noted the company was one of three with lower-than-average code complaint rates in the Review-Journal’s analysis.

“Eviction is always a last resort for us,” she said. “We always want to work with residents to keep them in those homes.”

That’s the approach all major single-family rental companies take, said National Rental Home Council executive director David Howard, whose trade association represents Invitation Homes and four other corporate landlords included in the Review-Journal’s analysis.

READ MORE

Howard said companies represented by the National Rental Home Council are using cutting-edge technology to provide their tenants with around-the-clock management services, and some have offered extended payment programs for tenants facing financial hardship.

“The practice of evicting tenants is not part of the business model of any legitimate company in this business,” he said. “To the contrary, the entire business is predicated on providing a seamless experience for tenants in order to keep them in their homes.”

‘I felt like a prisoner’

Financial insecurity was a common thread among current and former King Futt’s tenants who spoke with the Review-Journal. While the company performs criminal background checks on prospective tenants, it does not check their credit scores — a practice that can be a lifeline for people who have trouble renting elsewhere in Southern Nevada’s increasingly tight housing market.

That was the case for Connie Lewis, who said she was feeling desperate to find a new home in 2015 when she temporarily separated from her husband. Most landlords weren’t interested in renting to a single mother whose only source of income was being paid small amounts of cash by family to take care of her elderly grandmother.

King Futt’s appeared to be her family’s salvation, offering a three-bedroom home in North Las Vegas for only $790 a month. Lewis and her two daughters moved into the home in May 2015.

“I thought I was just blessed,” said Lewis, 47. “I didn’t question it. I was just happy to get in there.”

Her opinion began to change the day she moved in. Two refrigerators filled with mold sat in the home’s front yard, she said, and garbage bags full of trash were piled against one side of the house.

Lewis said she was constantly finding new problems with the home — including leaky plumbing, loose carpeting and regular encounters with centipedes and scorpions — but she had difficulty getting King Futt’s to perform maintenance. When the metal security door protecting her back door stopped locking, Lewis said the company told her she would need to pay for a replacement.

“Once they got me in, they acted like I was a burden on them,” she said. “If you called looking for help with something wrong with your house, they looked for ways to say it’s your fault. And I lived in a very dilapidated house.”

In a written statement, King Futt’s said that the metal door could not be repaired and that Lewis declined the company’s offer to remove it from the house. The company also wrote that a leak in Lewis’ master bathroom was repaired at no cost to the tenant. The company declined to comment on the condition of the home when she moved in.

The company wrote that tenants’ leases stipulate they are responsible for pest control services after their first 30 days in a home — along with any landscaping costs and all repairs under $100.

“We try very hard to make our tenants happy,” Ben-Samochan said. “It’s possible going in they didn’t understand what they’re responsible for.”

Despite her complaints, Lewis continued to renew her lease and lived in the home for four years before being evicted this June for falling behind on rent. She would have moved elsewhere sooner if she had the money.

“I felt like a prisoner,” she said. “I needed the house because of the price.”

Seymour said tenants like Lewis who have little income, bad credit or an eviction on their record are vulnerable to exploitation because they likely have few options to rent elsewhere.

“They have little to no power in that tenant-landlord relationship,” he said. “We’re talking about some of the bottom rungs of the ladder before homeless.”

‘No accountability’

One Las Vegas family evacuated their King Futt’s rental home in March 2017 amid concerns a mold infestation was putting their health at risk. They later sued the company.

Teresa and Joe Jaffer reported a leak in the master bathroom early that month, according to the family’s lawsuit. A few days later King Futt’s dispatched an employee who broke open the bathtub’s tiled siding and drywall, exposing the mold, Teresa recounted in an email to the company sent the day of the incident.

“It was almost like a disease,” Joe told the Review-Journal during a recent interview. “It was just disgusting.”

That night, Teresa sent King Futt’s an email stating her head began hurting just minutes after the mold cavity was opened; the symptoms lasted for hours, even after she stepped outside the home.

Photos attached to the email show large pieces of the broken wall piled on the bathroom floor, their backs covered in dark-colored mold. The family’s lawsuit alleged the handyman did not seal off the bathroom from the rest of the house before starting and that he replaced the drywall and tiles without removing all the mold.

One mold remediation expert, who reviewed the photos at the Review-Journal’s request, said the job was mishandled in a potentially dangerous way.

“This shouldn’t have happened,” said Chris Gusick, owner of Adaptive Environmental Consulting in Las Vegas. “If you break it apart like this, you’re going to release millions, if not billions, of spores into the air. That’s all going to settle on something.”

An air quality sample taken five days later showed elevated levels of mold not only in the rental home’s master bathroom, but also in the living room and kitchen, according to an apparent lab analysis provided by the Jaffers.

The Jaffers’ lawsuit alleged King Futt’s took more than a month to properly remove the mold from the home. The company wrote in a statement to the Review-Journal that the family was “extremely argumentative” and made fixing the mold problem “an almost impossible task every step of the way.”

During their displacement, the Jaffers said they paid their full $1,250 rent for March and April 2017. Meanwhile, the family of four spent more than $1,800 to split single rooms at nearby hotels through early April, according to copies of receipts they filed as court exhibits. Court records show King Futt’s had initially offered to compensate the family $75 for each day they stayed in a hotel, but Joe said his family never received any reimbursement.

The family handed their keys back to King Futt’s in May 2017 after the company took steps to evict them for withholding that month’s rent. Their lease had been scheduled to expire June 1.

The Jaffers sued King Futt’s in Clark County District Court, claiming the company had been negligent. King Futt’s responded with allegations that the Jaffers had caused the mold to grow and that the family owed the company more than $15,000 in damages. The family and King Futt’s each denied the allegations made against them, and both parties agreed to dismiss the case in November 2017, including all claims for reimbursement.

More than two years later, Joe said, his family is still working to replace the savings they spent on their attorney, the hotels and the cost of replacing most of their clothing, which they feared the mold had contaminated.

“They can bleed you dry going through court, so it’s not like there’s any recourse for the tenant,” he said. “They have no accountability.”

Long-lasting consequences

Even after they left their King Futt’s rentals, some former tenants said they’ve received exorbitant bills from the company.

When DeLoach was negotiating her family’s early departure from their rental in December 2018, emails show she asked the company to conduct a move-out inspection with her. King Futt’s staff never answered the request, DeLoach said, nor did they respond to her repeated inquiries about receiving her $1,275 security deposit.

Her family moved to Arizona and then Texas, thinking the experience was behind them. DeLoach said King Futt’s never responded to multiple emails she sent asking for an itemized move-out bill, but this fall she received a collections agency invoice claiming she owed the company an additional $2,100.

In a written statement to the Review-Journal, the company alleged the former tenant owed unpaid rent, late fees and utility bills. DeLoach said she is contesting the amount to remove it from her credit report; she doesn’t plan on paying King Futt’s.

“It’s very predatorial,” she said. “You’re already in a bad situation, and they put this on your credit. It just sets you back even more.”

Contact Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Davidson is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing. Follow @davidsonlvrj on Twitter.

READ MORE