In the remote desert northeast of Las Vegas, four federal officers faced a speeding pickup filled with suspected car thieves.

Two officers drew their guns, yet never fired.

But a Bureau of Land Management trainee, stationed high on a hillside as a lookout, fired eight shots from an AR-15 into the stolen 2000 tan Chevrolet Silverado. Five bullets hit the back of the truck after it appeared to veer away from a police vehicle and went off the road into a deep flood wash, landing on its side.

The bullets killed Greg Davis Sr., 52, and injured the two other suspected thieves. All had extensive criminal histories. Cody Negrette, the trainee who had worked for the BLM only a few months, is heard on bodycam video saying: “I hit all three of ’em.”

The detailed events of that March day are only now public because a source concerned about the lethal shooting and subsequent probe of the confrontation provided exclusive investigative records and hours of officers’ bodycam video to the Review-Journal.

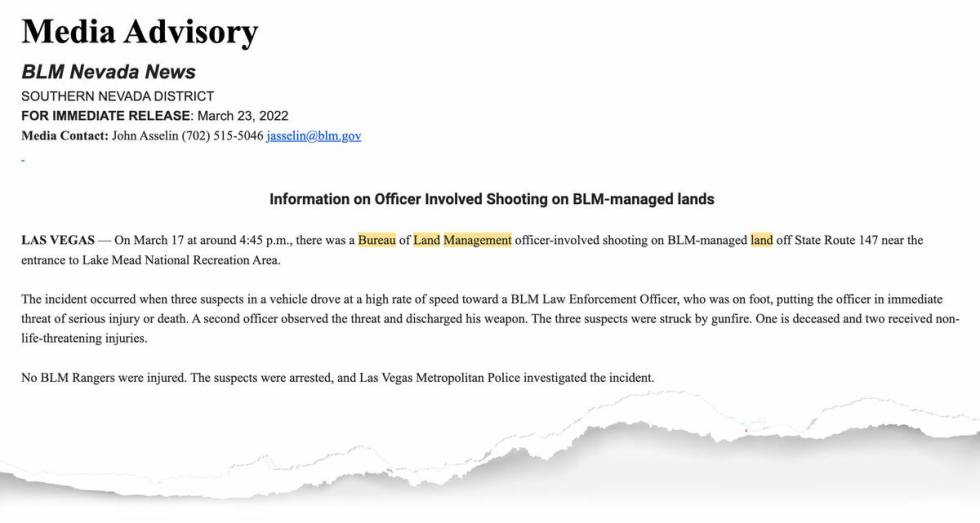

Previously, BLM released just three short sentences to the media on March 23 — the extent of information made public. No briefing was held on the officer-involved shooting.

Policing experts, who reviewed the documents and some of the video at the newspaper’s request, say the records reveal a questionable use of force and a flawed Metro Force Investigation Team review. Davis’ family and friends say mistakes were made.

Carlos Cardenas

Greg Davis

Eric Orrantia

In the ensuing months, BLM and Metro officials have denied or failed to respond to repeated requests to release information, including officers’ names and bodycam video, which is required in BLM’s deadly force agreement with Metro police. Metro declined to release information, citing the ongoing criminal case against the Silverado’s driver and directing the request to BLM.

The Justice Department denied a Review-Journal FOIA request about whether the office considered criminal charges in the Negrette shooting, declining even to confirm whether the U.S. attorney’s office in Las Vegas reviewed the case.

Jason C. Fries, who has served as an expert witness for 23 years in officer-involved shootings, said it makes no sense that the officers who told investigators they were in danger didn’t fire their guns — but the officer who was farthest away did.

“There are a lot of reasons not to shoot at a moving vehicle,” said Fries, who is CEO of 3D Forensic, which reconstructs police shootings for investigators and court cases. “The officer who shoots puts the (other) officers in danger. Having an uncontrolled car around fellow officers is never a good thing.”

A use-of-force policy paper, released in 2020 by 11 top law enforcement associations, cautioned that shooting at a moving vehicle should only be done when there are no other alternatives.

Negrette declined to comment when reached by phone, saying he isn’t allowed to discuss the shooting until the driver’s criminal case is resolved. The other four officers could not be reached for comment or did not return calls.

In his FIT interview four days after the shooting, documents show Negrette said that the moving truck was “an imminent threat to one of my officers. And so I acted accordingly.”

BLM would not confirm if Negrette is still with the agency or release its policy on officer-involved shootings and data about the agency’s force cases.

Davis’ girlfriend, Alicia Reed, said police overreacted to a nonviolent offense of the three men stripping two vehicles in the desert.

“Greg was up there committing a crime,” Reed said. “I absolutely get that. My thing is, he deserves to be in jail. … He doesn’t deserve to be dead.”

Davis’ ex-wife, Yvonne Efverlund, said Metro and BLM officials gave her the runaround when she tried to obtain more information about her ex-husband’s death.

“It’s a cover-up,” she said. “They’re trying to cover up … everything because I think they all made mistakes.”

B. Sones

M. McCall

K. Waring

C. Negrette

T. Austin

From K-9 arrest to fatal shooting

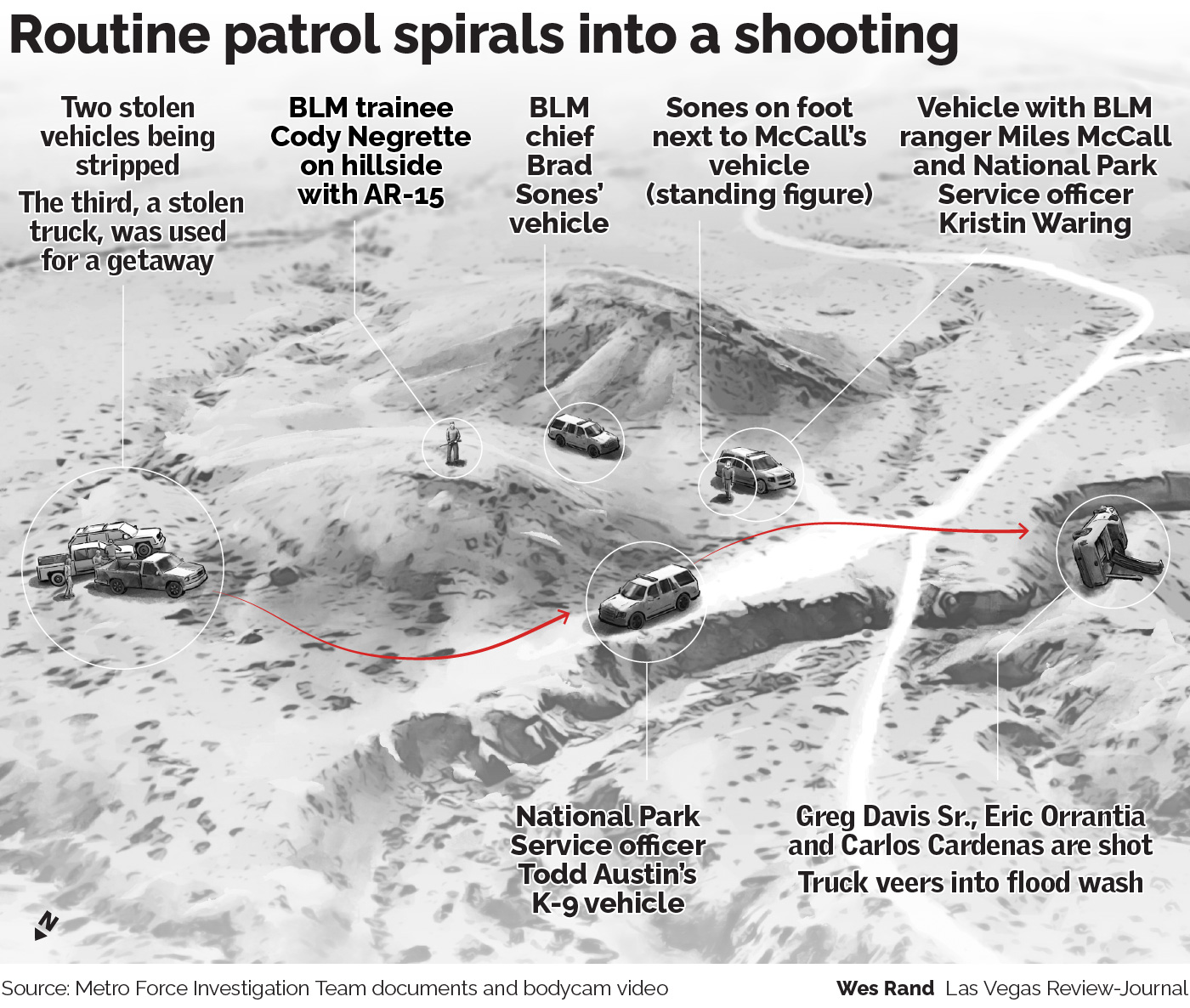

The March 17 shooting started as a routine patrol.

BLM chief Brad Sones and Negrette were driving around East Lake Mead Boulevard and spotted Eric Orrantia, Carlos Cardenas and Davis dismantling two stolen vehicles at about 3:45 p.m., police records said. All of the men had arrests, mostly for drugs and theft. Davis’ family said Orrantia and Davis were roommates but didn’t know Cardenas.

Outnumbered, Sones called for backup, bringing BLM ranger Miles McCall, and two National Park Service officers, Kristin Waring and Todd Austin with his K-9, to the desolate area.

On state Route 147 at mile marker 10, Sones, McCall, Austin and Waring parked their vehicles, intending to confront and arrest the men with the help of a police dog.

Sones told Negrette, who served in the Marines, to go up on the hill as a lookout and gave Negrette his AR-15 rifle equipped with a scope, court records show.

Sones, the lead officer on the scene, did not turn on his body camera until after the shooting.

The thieves spotted the officers at 4:38 p.m. and jumped into a Silverado. They barreled down a narrow dirt road cut into the hillside that led out of the area, records and video show. Several of the men previously had been charged with fleeing police.

Seeing the officers’ vehicles, Orrantia, who was driving, initially slowed down, but then gunned the truck toward park officer Austin’s vehicle, records show. He swerved left to avoid Austin, then headed towards Sones, who was on foot outside his vehicle. The Silverado came as close as 24 feet to the chief, the Metro FIT report said.

As Orrantia was turning the truck to avoid Sones and apparently trying to escape, Negrette, who was about half the length of a football field away, fired a burst of three rounds, his bodycam video shows. As the vehicle skidded toward the flood wash, Negrette fired five more shots into the back of the truck.

Negrette’s LinkedIn profile shows he has a varied history of jobs since leaving the U.S. Marine Corps in 2016. He worked three months as a U.S. Forest Service firefighter, less than a year as a park ranger for Phoenix, and nine months as an EMT for a company that freezes humans with the hope future science will be able to revive them. He started at the National Park Service in 2019 and joined BLM in November 2021, records show.

Two of the vehicles that were being stripped are part of the FIT report. (Metro FIT unit investigative file photos)

Two of the vehicles that were being stripped are part of the FIT report. (Metro FIT unit investigative file photos)  The overturned truck driven by the suspected car thieves. A BLM trainee shot seven rounds into the vehicle, killing the passenger in the front seat. (Metro FIT unit investigative file photos)

The overturned truck driven by the suspected car thieves. A BLM trainee shot seven rounds into the vehicle, killing the passenger in the front seat. (Metro FIT unit investigative file photos)

History of arrests

After Negrette’s shots hit the Silverado, it quickly went off an embankment and flipped, coming to rest on the passenger’s side door. Orrantia and Cardenas ran from the truck.

Cardenas, 33, who goes by the nickname “Tweety,” was shot in the back and left arm. He didn’t make it very far. Officers handcuffed him and started treating his wounds.

Cardenas served prison time for a felon with a weapon, failing to stop for police and having a stolen credit card, Nevada Department of Public Safety records show. He had a large 28th Street back tattoo, which police say signified a gang affiliation. He pleaded guilty to possessing a stolen vehicle and tampering with vehicles for the March arrest and was sentenced to a maximum of three years.

Orrantia, also 33, whose nickname in police files is “Menace,” was able to get farther despite Negrette shooting him in the right foot. Parks officers and a police dog tracked him down near East Lake Mead Boulevard. He previously served prison time for several stolen property and drug charges over the past decade. For the March confrontation, he is charged with assault and attempted murder for driving toward officers and a number of other offenses.

At a preliminary hearing in August, Orrantia, who pleaded not guilty, maintained through his attorney, Philip Singer, that the assault and attempted murder charges are a way to cover up the flawed shooting.

“No one was scared,” Singer said at the hearing. “No one fired their weapon. … The only reason that the charges were filed …it’s basically to keep Negrette’s job or to save face.”

Singer, whose law license was reinstated last year after a 2008 suspension for misappropriating client funds, did not return repeated calls.

Dead or alive?

Davis, sitting in the passenger seat of the Silverado, had drug arrests and pointing a gun at a person conviction, police records show. They were crimes to support his meth habit and make ends meet when he couldn’t find work or was too ill to practice his tile-laying profession, court records and friends say.

He suffered five gunshots from Negrette’s rifle, including one to the back of the head. When the truck rolled, it blocked his door.

Right after the shooting, Sones approached the vehicle calling to Davis while Negrette, who had descended from the hillside to the road, stood watch.

“There’s one dead in the car,” Sones said.

“Hey, he’s not dead,” Negrette responded. “He made a noise.”

No bodycam video shows officers opening the driver’s door to check on Davis, offering medical aid or climbing in the Silverado to determine if Davis was still alive. Negrette had the training to do so, later telling investigators that he was a “Nationally Registered EMT.”

Video shows the officers were worried about making sure Davis wasn’t a threat. No weapons were seen during the escape, but authorities hours later found a loaded Derringer in a tool bag on the floor of the Silverado near Davis with his DNA on it, investigative records show.

“We need to clear this vehicle,” Negrette calls out. “We need to make sure he’s not armed.”

At 4:43, officers called for medical help for Davis and Cardenas, FIT records show. The records also show at 5:04, information was broadcast that one suspect was dead. It’s unknown who made that determination.

BLM officer Chris Allen, also armed with an AR-15, arrived a few minutes after the shooting. Negrette told him the suspect truck was driving towards the officers when he fired the shots.

Video shows about six minutes passed when Sones walked up the embankment to tell Negrette that Davis was dead.

“He’s going to be dead,” Sones said. “He’s shot in the back of the head.”

Then Sones ordered Negrette away from the scene and assigned Allen as his support officer during the investigation.

Negrette started to talk about the shooting, but Allen motioned to cut him off, video shows.

“This is on,” Allen cautioned, pointing toward his body camera.

FIT unit history

Metro’s FIT unit was formed in 2012 by then-Sheriff Doug Gillespie in response to a series of high-profile Metro shootings that were documented in a Review-Journal investigation.

The questionable shootings attracted the interest of the U.S. Justice Department, which offered to help reform the agency’s training and investigations.

When FIT completes an investigation of a Metro shooting, the detectives refer it for potential criminal conduct to the Clark County district attorney’s office, and internal affairs determines whether there were policy violations.

Metro officials hold a news briefing to release reports and video from the shooting.

FIT was so well-regarded that local police departments, state and federal agencies entered into agreements to investigate their shootings if they happen in Clark County.

Each of the outside agencies has a memorandum of understanding with FIT.

Key questions not asked

Negrette’s and other officer interviews show FIT detectives repeatedly appear to lead federal officers to say their lives were in danger before the shooting, according to experts who reviewed the transcripts.

Retired Rockford, Ill., police Chief Chet Epperson, who serves as an expert witness in police force cases, said the FIT investigation was not conducted properly.

“They’re already leading the person,” he said after being read quotes from the transcripts. “Not everyone wants the truth. That’s why in many investigations, unfortunately, the police don’t ask the right questions.”

FIT detectives did not ask a key question of why the officers, who said their lives were endangered, failed to fire at the truck to defend themselves, expert said.

“When you saw that truck driving at you, how did that make you feel?” Detective Gilberto Valenzuela asked Sones according to the interview transcript.

“Uh, scared, uneasy, you know,” Sones answered in the recording. “I’ve never been that close to a car driving that fast.”

There were no questions posed to Sones about the rifle provided to Negrette or the decision to use lethal force, transcripts show.

Detective Blake Penny used similar phrasing with Negrette. His interview happened four days after the shooting, which is allowed by federal rules.

“You just saw a fellow officer standing, um, in the open with no protection with this truck heading right towards it?” Penny asked.

“Right at ’em,” Negrette answered.

“Um, had they hit him — um, you said there was an imminent threat. You know, had they hit ’em, what could’ve happened to that, um, officer?” Penny asked

“Serious injury or death,” Negrette said.

Investigation objectivity?

During her interview with the FIT unit, Waring seemed to waver from the imminent danger assertion until FIT detectives brought her back to it, the interview transcript shows.

You “pull your gun out and you point — you’re pointing it through the windshield,” Penny asked her. “Um, were you concerned for your — enough for your safety that you were prepared to use deadly force to stop that vehicle before it hit you head-on?”

“If something else had changed, yes,” she answered.

Penny responded: “You’re obviously in fear for your safety, McCall’s safety and Chief Sones’ safety?”

In Orrantia’s August court hearing, Waring testified that she didn’t have a “safe opportunity” to fire her gun and that a large amount of dust prevented her from seeing the situation clearly.

Metro declined a request for interviews conducted for other Metro FIT investigations, calling it too burdensome, but provided a sample from one recent case. Those interviews had similar questions, leading Epperson to question the FIT unit’s objectivity.

“If you’re seeing those leading questions, then you have to ask if those are the same interview techniques used (in other investigations),” he said. “That’s a concern.”

Davis’ girlfriend, Reed, maintains the officers were not in danger.

“They weren’t in as much danger,” said Reed, whose son is a North Las Vegas police officer. “It’s an unjustified shooting, 100 percent. It was a shooting gone wrong that they overreacted and then they lied … to cover it up.”

Struggling with addiction

Davis had grown up in an abusive home in Southern California and struggled with his own drug addiction, according to Reed and Efverlund. Despite that, he worked hard in his profession of laying tile.

The drug lifestyle led Efverlund to divorce him in 1998, five years after they had a son. But they remained friends.

When the 2001 recession hit and tile work in Los Angeles dried up, Davis moved to Las Vegas. He found employment as a tile installer, earning a reputation for high-quality work. He laid tile at Caesars Palace and in million-dollar homes around the valley, Efverlund said.

Starting in 2008, Davis was arrested on a felony for possessing a gun, drugs and DUI, Department of Public Safety records show. He pleaded guilty to possession of meth in 2009 and pointing a gun at a man in 2020, court records show. An autopsy found Davis had meth in his system when he died, records show.

Manual labor and drugs were taking a toll on Davis’ body. He had his shoulder reconstructed and could no longer lift large tiles he had become so skilled at installing, Reed said. Davis resorted to collecting cans and bottles to buy food, Reed said.

After the March shooting, officers and the Clark County coroner staff decided to leave Davis’ body in the truck until morning because it was getting dark and it would be safer for investigators to remove it the next day, records say.

“I’m sure he could not have survived, but to not even check and to leave him by himself to die is just, it’s inhumane,” Reed said after learning what happened from the Review-Journal.

Efverlund and Reed said they plan to hire attorneys to sue for wrongful death and obtain more information about the shooting.

Over the past 12 years, Metropolitan Police Department officials have held about 90 briefings about fatal police shootings, releasing bodycam video, reports, internal affairs reviews and the district attorney’s decisions on whether to prosecute.

But when Metro’s Force Investigation Team looks into shootings by outside agencies, the process is far less transparent, the Review-Journal found.

FIT investigates fatal police shootings in Clark County for 10 outside local, state and federal agencies, including the Nevada Department of Public Safety, North Las Vegas and the Bureau of Land Management under separate memorandums of understanding.

An investigation into a March 17 shooting by a BLM trainee in the desert was completed in May, but the BLM refused to release documentation about the shooting, citing an exemption for “law enforcement records.”

In that incident, trainee Cody Negrette shot three men, who were observed stripping vehicles east of Las Vegas, as they eluded officers. One man, Greg Davis Sr., was killed; two were injured. Veteran officers did not fire weapons.

The memorandum of understanding with the BLM specifically requires the federal agency to respond to media inquiries and release the names of the officers involved in the shooting.

But BLM and Metro have declined repeated requests for interviews and won’t identify officers involved in recent shootings.

The Review-Journal obtained investigative documents and bodycam video from a source.

Experts who reviewed the report transcripts criticized the actions of FIT detectives, saying they improperly led witnesses and failed to ask key questions.

Davis’ ex-wife, Yvonne Efverlund, has been fighting to obtain records about the shooting and said she has received nothing from either the BLM or Metro.

“They do not have to release any information,” she said.

FOIA failure

The BLM and other federal agencies either denied the Review-Journal’s Freedom of Information Act requests or refused to expedite them under a provision for breaking news.

The response to expedite a request about Negrette’s work history was denied because FOIA officers could not find news stories about him in a Google search. But his name didn’t come up in web searches because BLM refused to release his name.

The Justice Department denied a Review-Journal FOIA request about whether Nevada’s U.S. Attorney’s office considered criminal charges in the Negrette shooting, declining even to confirm whether the case was reviewed.

The BLM would not provide the number of officer-involved shootings that FIT investigated during the past decade.

But bodycam footage from officers at the Davis shooting seems to indicate a number of incidents that did not make the news.

Negrette discussed the Davis shooting with colleague Chris Allen, according to bodycam video. Allen appeared to indicate he had been part of a FIT investigation.

“You have more experience in this than I do,” Negrette said.

“Like for mine, the best I can tell you is wait ‘til the FIT team gets here,” Allen said. “They’ll ask you the basic officer safety questions. Kind of what happened.”

More shooting inquiries

Two other officers who were helping to transport a man Negrette shot in March also discussed their shooting investigations.

“Yeah, I’ve been there,” a BLM officer identified as N. Wadford tells an unidentified officer, according to his body camera video. “I don’t want to do that again.”

“Yeah, I was involved in the (unintelligible) one,” the other officer responds. “I was with you guys for a while. I decided to transfer just to let the heat go away, you know.”

Both officers laugh.

Efverlund said Metro FIT Detective Blake Penny told her to get the information from BLM, and BLM either failed to respond to her FOIA requests or said the information should come from Metro. She said when she called the agency demanding to speak with someone, an unknown BLM worker hung up on her.

Contact Arthur Kane at akane@reviewjournal.com and follow @ArthurMKane on Twitter. Kane is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing.

The Bureau of Land Management oversees nearly 70 percent of Nevada with 48 million acres under their supervision. Nationwide, the agency has a $1.3 billion budget and more than 10,000 employees. Fewer than 100 of them are with the Resource Protection and Law Enforcement division though that section has a budget of more than $27 million, according to the 2021 budget.