Emerging extremists bring new concerns for law enforcement

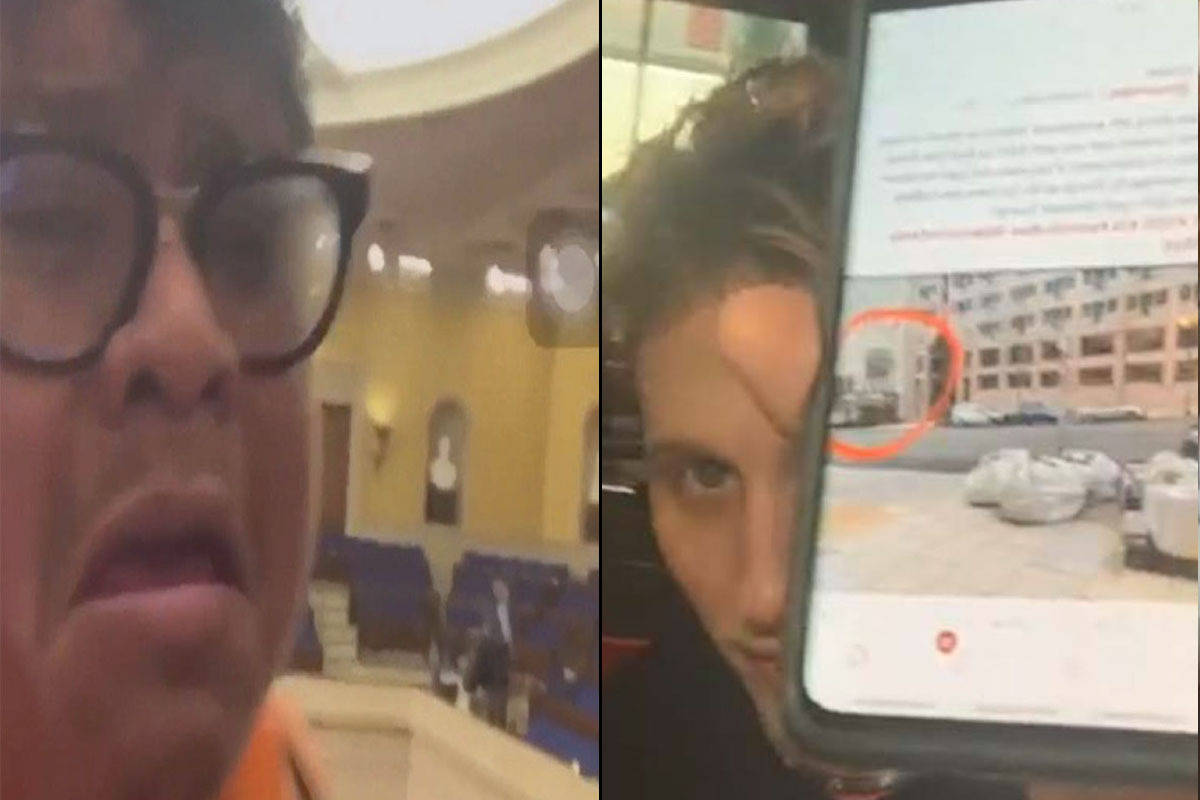

When Ronald Sandlin and Nathaniel DeGrave appeared in federal court in Las Vegas last month on charges of participating in the Capitol Hill riot, prosecutors could not link them to any extremist group.

They were not members of the Proud Boys or Oath Keepers, who stand accused of conspiring to plan the deadly Jan. 6 attack on Congress. And both men had no serious criminal background.

But like hundreds of others caught up in the Capitol Hill mob, they shared some of the same grievances, particularly the false belief that the election was stolen from former President Donald Trump.

Real estate agents, business owners, professionals, police officers, military members and veterans all joined the attack alongside hard-core extremist groups, according to experts and national media reports.

“Emerging right now is kind of a larger ilk of individuals who fully embrace conspiracies and disinformation that have been widely peddled from the highest levels of our country, including our former president,” said Joanna Mendelson, associate director of the Center on Extremism for the Anti-Defamation League. “This is not something that is going away.”

In Southern Nevada, authorities are aware of the broadening spectrum of extremism, fueled in part by months of COVID-19 isolation and online venting.

And they are concerned.

“We live in a world now where where grievances can be established very quickly, solidified by chatting with other people in special social media platforms or online groups, and then action occurs immediately thereafter,” said Deputy Chief Andy Walsh, who oversees the Homeland Security Division for the Metropolitan Police Department.

“The challenge for law enforcement is determining the difference between someone who is ranting and raving and someone who is capable of carrying out an act of mass violence.”

In a report this month, the Southern Poverty Law Center said the proliferation of extremist internet platforms has allowed people to engage with potentially violent movements like QAnon and boogaloo “without being card-carrying members” of any group.

Sandlin’s Las Vegas lawyer Russell Marsh said in an interview that his client “just got pulled into it because of his support for former President Trump.” DeGrave’s public defender told the judge that DeGrave was a “follower,” not a leader.

Federal prosecutors tied Sandlin to two separate assaults on law enforcement officers at the Capitol and called his conduct “extremely troubling.” He is accused of trying to rip one officer’s helmet off and getting into a shoving match with another officer.

DeGrave wore full body armor and tactical gear during the assault and became aggressive, prosecutors alleged. Both men exchanged messages on Facebook in the week leading up to the attack.

Pressure on law enforcement

Brian Levin, director of the Center for Study of Hate & Extremism at California State University in San Bernardino, said the expansion of extremism is putting more pressure on law enforcement authorities.

“There’s going to be a whole change across the law enforcement horizon on how they deal with this new insurgency,” he said. “Law enforcement will have to get a new grip on how they coordinate intelligence and engage with various groups at conflictual events. These groups believe that there is a groundswell of support for what they’re doing, and that tells us the depth of the polarization.”

Walsh said authorities now have to look at domestic radicalism in the way they focused on international threats of terrorism in the years after Sept. 11, 2001, from such groups as al-Qaida and and ISIS.

“The elements are basically the same,” he said. “They feel disenfranchised, have a grievance, find others that identify with them and they take action either individually or with a group.”

Chief Deputy District Attorney Michael Dickerson, who has been prosecuting the terrorism case against suspected members of the right-wing boogaloo movement, said 2020 saw a lot more people stuck inside their homes because of the COVID-19 pandemic connecting with others and expressing their frustrations online.

Sometimes they have self-radicalized, Dickerson said.

“You can potentially go online and go down a rabbit hole of conspiracy theories to put yourself in a negative feedback loop,” he said. “You just continue going further in. Then, you make decisions without full regard for the consequences of your actions.“

Mob mentality

Thomas Pitaro, who has seen the gamut of criminal cases in his decades-long career as a defense lawyer and part-time UNLV law professor, thinks that is what happened to many of the Capitol Hill rioters who came out to protest.

They simply got caught up in the mob mentality, he said.

“I don’t think they realized what they were doing and how un-American it was,” Pitaro said. “They were in it for the thrill. This wasn’t disorderly conduct in some sort of downtown rally. They attacked a fundamental portion of government while it was doing its constitutional duty.”

And now they are paying the price.

In the case against Sandlin, 33, and DeGrave, 31, U.S. Magistrate Judge Daniel Albregts had little sympathy for the two men after their arrests at DeGrave’s Las Vegas apartment.

Albregts ordered the duo detained and transported to Washington, D.C., to face the riot charges, saying they showed an “utter disregard and utter lack of respect for the nation’s most sacred institutions.”

Between video surveillance at the Capitol and their own social media accounts, prosecutors presented enough evidence to justify keeping Sandlin and DeGrave behind bars.

The New York Post published a video of an excited Sandlin smoking what appeared to be marijuana in the Capitol Rotunda while boasting, “We made history, this is our house.”

But in court, Sandlin wasn’t as brave as he appeared to be with the mob in Washington. He began sobbing and begged the judge to release him to his parents in Memphis, Tenn.

The harsh treatment of the defendants is an indication that authorities have zero tolerance for extremist acts in Nevada in this uncertain era of unrest.

“We fully support and will protect the exercise of constitutional rights. But we will not tolerate violence,” outgoing Nevada U.S. Attorney Nicholas Trutanich said in a statement to the Review-Journal. “If anyone seeks to spark violence, our office’s role is clear: Along with our law enforcement partners, we would hold accountable any agitators who interfere with the rights of peaceful protesters in Nevada.”

Local elected leaders are also standing up to the growing threats.

“Clearly, we’ve seen events taking place that are wrong and don’t reflect the values of our residents and the best of our community,” said Clark County Commissioner Michael Naft, who worked to get the county to issue a proclamation denouncing hate and extremism.

“With a new administration in Washington, I think it would be a mistake to think these problems won’t exist anymore.”

Extremism and hate

Nevada has seen several instances of extremism and hate crimes in recent years.

Some examples:

— Two self-styled anti-government revolutionaries, Jerad and Amanda Miller, shot to death Las Vegas police officers Alyn Beck and Igor Soldo at a pizza restaurant in June 2014. The couple, who had been steeped in conspiracy theories, died after a shootout with police at a nearby Walmart. A third man, Robert Wilcox, was killed by Amanda Miller as he tried to stop the couple at the Walmart before police showed up.

— Members of a neo-Nazi group known as Atomwaffen Division were reported to have spent three days in the Nevada desert near Death Valley in January 2018 conducting weapons training. People with links to the group were charged in several slayings outside Nevada, according to the nonprofit news organization ProPublica.

— Matthew Wright, a Henderson man and suspected QAnon conspiracy follower, was sentenced to prison in December for using his armored vehicle to block a bridge near Hoover Dam and making a terrorist threat in a standoff with authorities in June 2018. His lawyer said he was protesting the government handling of the Oct. 1, 2017, mass shooting at the Route 91 Harvest festival in Las Vegas.

— Connor Climo received a prison term in November for planning violent attacks in 2019 against the Anti-Defamation League and a Las Vegas synagogue. Federal prosecutors alleged that Climo had been communicating with people tied to the white supremacist group Feuerkrieg Division.

— John Dabritz, described by law enforcement as displaying signs of anti-government extremism, was charged in the March 2020 shooting death of Nevada Highway Patrol Sgt. Ben Jenkins. The case was singled out by the ADL as one of 16 instances in which police and extremists exchanged gunfire in 2020. Dabritz’s trial is set for September.

— Three suspected members of the right-wing boogaloo movement were indicted in June in a scheme to cause violence at Black Lives Matter protests. Stephen Parshall, Andrew Lynam and William Loomis all face felony charges, including terrorism and conspiring to cause destruction by fire and explosive. Trials await them later this year.

— Members of the Proud Boys appeared at ReOpen Nevada and Black Lives Matter protests in Las Vegas and Reno last year. Experts have described them as “racist street fighters” of the far-right known for engaging with brawls with left-wing groups. The Proud Boys held a national gathering called WestFest in Las Vegas in September 2017.

The Bundy standoff

In one of Nevada’s more notable anti-government clashes, Bunkerville rancher Cliven Bundy and his militia supporters engaged in an armed standoff with the Bureau of Land Management in April 2014 over the federal agency’s roundup of his cattle.

Bundy and several of his supporters, including some of his sons, were charged in the showdown. But a federal judge later found government misconduct in the high-profile case and dismissed the charges against Bundy and his sons.

One of those sons, Ammon Bundy, made headlines recently for anti-government actions in Idaho and elsewhere in the Northwest, as part of a new group he formed in 2020 called People’s Rights, to organize against coronavirus restrictions and other perceived government overreaches.

Bundy, 45, known for being one of the leaders of the deadly 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, recently told the Los Angeles Times that his new grassroots network had about 50,000 people in 35 states. The network, which he described as “neighborhood watch on steroids,” has recruited through social media.

The Southern Poverty Law Center suggested that Bundy is attempting to build a “network of right-wing, often anti-government activists” that can be mobilized quickly if needed.

Bundy did not respond to a request for comment.

Joshua Martinez, 32, the director of the Nevada operation, said the group is still organizing herebut has 415 members.

“We defend everyone’s rights,” said Martinez, who calls himself a “huge” fan of the Bundys. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a liberal or a Republican. We try to use the bullhorn.”

So far, Martinez said he’s spending most of his time keeping an eye on police when they stop people on the streets.

“We try to keep things peaceful,” he said. “Ammon wants everything peaceful.”

Cliven Bundy, 74, who spent two years behind bars while fighting his criminal case, said in an interview that his son is just trying to give people support when he sees them being treated unfairly.

Since his own case was tossed out three years ago, Bundy said, his life has been confined to raising cattle and growing melons at his ranch.

But he still counts himself among the growing number of Americans who are unhappy with the government.

He said he didn’t back the mob that moved against the Capitol but remains a Trump supporter, believing the election was stolen from the former president.

“Look at all of the evidence that’s out there,” he said, adding he wished Congress would have addressed election fraud. “I don’t think there’s justice at all anymore.”

Bundy also said he didn’t believe Trump incited the riot.

“He was the president of the United States,” Bundy said. “He didn’t approve of it. He had people come there and join him in protest. But he told them to go up there and be peaceful.”

Contact Jeff German at jgerman@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4564. Follow @JGermanRJ on Twitter. German is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing. Support our journalism.