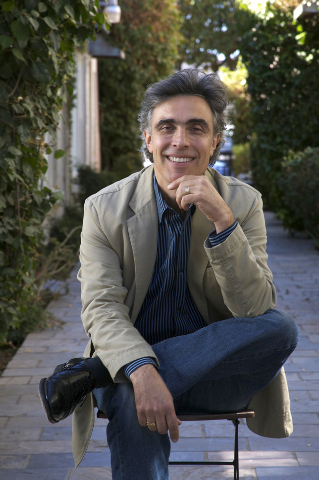

‘Rising Star’ Alexander Schimpf headlines Philharmonic concert

Alexander Schimpf headlines Las Vegas Philharmonic’s “Rising Star” Masterworks concert Saturday at The Smith Center’s Reynolds Hall.

In many respects, however, Schimpf’s star has already risen.

The award-winning German pianist — who’s on a five-week, nine-city U.S. tour — will perform Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor with the Philharmonic.

Guest conductor David Lockington — who presided over the Philharmonic’s 2013 season finale in May — returns to lead the orchestra in a program that includes Mussorgsky’s “Dawn Over the Moscow River” (the prelude to the composer’s opera “Khovanshchina”) and Sibelius’ Symphony No. 2 in D major.

Saturday’s concert not only marks Schimpf’s Las Vegas debut but the first time he’s performed the Tchaikovsky concerto in concert — which seems a bit surprising considering the effect the piece had when he first heard it.

Schimpf was “12 or 13 when I heard it for the first time, live,” he says in a telephone interview from a Seattle tour stop. “I was thrilled about that kind of music.”

His subsequent performances reflect that affinity for classical music.

Beginning with a first-place award in the 2008 German Music Competition (the first pianist in 14 years to win), Schimpf also captured first prize at Vienna’s 2009 International Beethoven Competition. In 2011, Schimpf became the first German pianist to win the Cleveland International Piano Competition, where his performance with the renowned Cleveland Orchestra earned him a standing ovation — and the audience prize.

Since then, Schimpf has performed from New York’s Carnegie Hall to St. Petersburg’s Maryinsky Theatre, where many of Tchaikovsky’s greatest works premiered.

Although “there’s always certain questions about the future,” the pianist acknowledges, “I’m pretty confident now that things will continue in a good way.”

Especially with the opportunity to perform works such as the Tchaikovsky concerto, which boasts “amazing melodies in all three movements,” Schimpf says.

One of Tchaikovsky’s most popular compositions, the concerto’s melodies still turn up outside the concert hall. (If you watched the closing ceremonies of the Winter Olympics in Sochi, you heard part of the concerto; its main theme inspired the 1940s hit “Tonight We Love,” and on screens big and small, it’s underscored everything from “Misery” to “Mad Men.”)

That sort of popularity comes as no surprise to Lockington.

“Every time you conduct one of the top 40 or top 100 pieces, you remember why it has its place in the repertoire,” he says. Such classics “have everything that reflects what it means to be human.”

Despite that human element, however, “you have to be almost superhuman to play it,” Lockington adds. “It’s extraordinarily difficult,” describing the concerto as “fistfuls of notes,” which a pianist must play “at speed.”

Overall, “it requires great accuracy, great delicacy and great power,” the conductor says. And “even if you can play the notes, you’ve got to fill them with music, you’ve got to fill them with soul — and you’ve got to fill the hall with music.”

No wonder “it’s a challenge to play well with the orchestra,” Schimpf says.

Make that orchestras.

“Each time you meet a new orchestra and play with a new conductor, there has to be a certain process of finding things together,” the pianist says. “I don’t like the concept of the soloist coming in and telling how things are going to be. It’s more giving and taking together.”

Lockington, by contrast, tries “to realize the performer’s vision of the piece,” he says. “I go through it with him before rehearsal and try to find out his approach, whether he’s heavier than heavy or quixotic.” That, in turn, helps the conductor — and the orchestra — provide “a steady framework” for the soloist.

“For me, that’s one of the joys of conducting — it’s like a mind-meld with the soloist,” Lockington adds. “It’s a great challenge. And a really exciting one.”

That challenge will be made easier because Lockington already knows — and likes — the Las Vegas Philharmonic, based on last May’s collaboration, when he conducted Holst’s “The Planets,” Mozart’s “Paris Symphony” and Wagner’s “Prelude and Liebestod” from the opera “Tristan und Isolde.”

Lockington says he “was impressed with the flexibility of the orchestra. They work very fluidly in different styles,” he says, citing the “really considerable” differences between the featured works. “I thought they handled it really well.”

As for The Smith Center’s Reynolds Hall, “I was really, really taken by it,” the conductor acknowledges. “I thought it was a space an orchestra could really grow into — and grow by performing in it.”

Little wonder, then, that Lockington has a simple reply when asked if he’s still in the running for the Philharmonic’s still-vacant music director post: “I hope so!” (Lockington will step down as music director of Michigan’s Grand Rapids Symphony after the 2014-15 season; Las Vegas Philharmonic officials expect to name the orchestra’s new music director in the coming months.)

Although the Tchaikovsky piano concerto was already on the Las Vegas Philharmonic schedule, Lockington chose the two works that round out Saturday’s program.

Mussorgsky’s operatic prelude serves as “a complement to Tchaikovsky,” the conductor explains, because it’s “from the same time” as the piano concerto, even though it represents “a different genre and a different musical ethos.”

Besides, both Tchaikovsky and Mussorgsky are Russian.

That Russian connection also informed Lockington’s choice of Sibelius’ symphony.

The Finnish composer’s work understandably “has such a Nordic feel to it,” but Lockington also cites the “interesting,” if far from positive relationship between czarist Russia and Finland. The Scandinavian country became an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian empire in 1809, sparking a nationalist movement several decades later.

Sibelius expressed his nationalism even more strongly in the symphonic poem “Finlandia,” which he composed “only a few years later,” Lockington says.

But his second symphony has “both a lightness and a seriousness about it,” the conductor says, noting the composer’s “use of silence,” along with the “noble, majestic and triumphant last movement.”

And although it’s “not a Tchaikovsky-like melody,” Sibelius’ symphony has “got a Tchaikovsky-like grandeur to it,” Lockington adds.

As for the Tchaikovsky concerto that Schimpf will finally perform in public, the process of discovery extends from rehearsals (one Friday, another Saturday morning) to Saturday’s performance itself.

“You also find out things just by playing,” the pianist says. “It can be real rewarding. I’m excited to find out.”

So is Lockington.

“I love the process of pulling it apart and putting it together, creating something exciting and moving,” the conductor says. “It’s a great miracle we’re all involved in.”

Contact reporter Carol Cling at ccling@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272.

Preview

Las Vegas Philharmonic, with pianist Alexander Schimpf

7:30 p.m. Saturday; pre-concert talk at 6:45 p.m.

Reynolds Hall, Smith Center for the Performing Arts, 361 Symphony Park Ave.

$25-$94 (702-749-2000, www.thesmithcenter.com)