John Fogerty recalls what made Woodstock so special

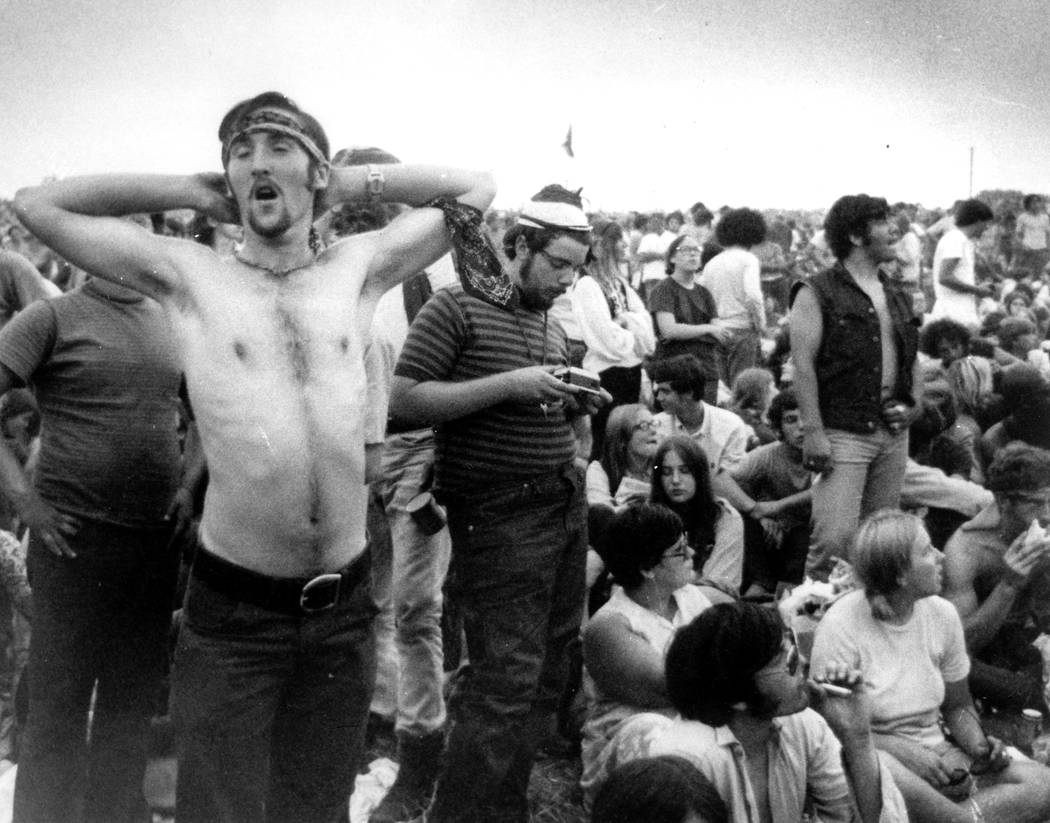

He couldn’t see much beyond the muck-spackled bodies, attired in dirt in lieu of clothes.

There John Fogerty stood, in front of half a million people, playing to one.

At the time, it all felt frustratingly anticlimactic for the Creedence Clearwater Revival frontman, who remembers the helicopter ride he took on Aug. 16, 1969, flying over a sea of humanity in upstate New York.

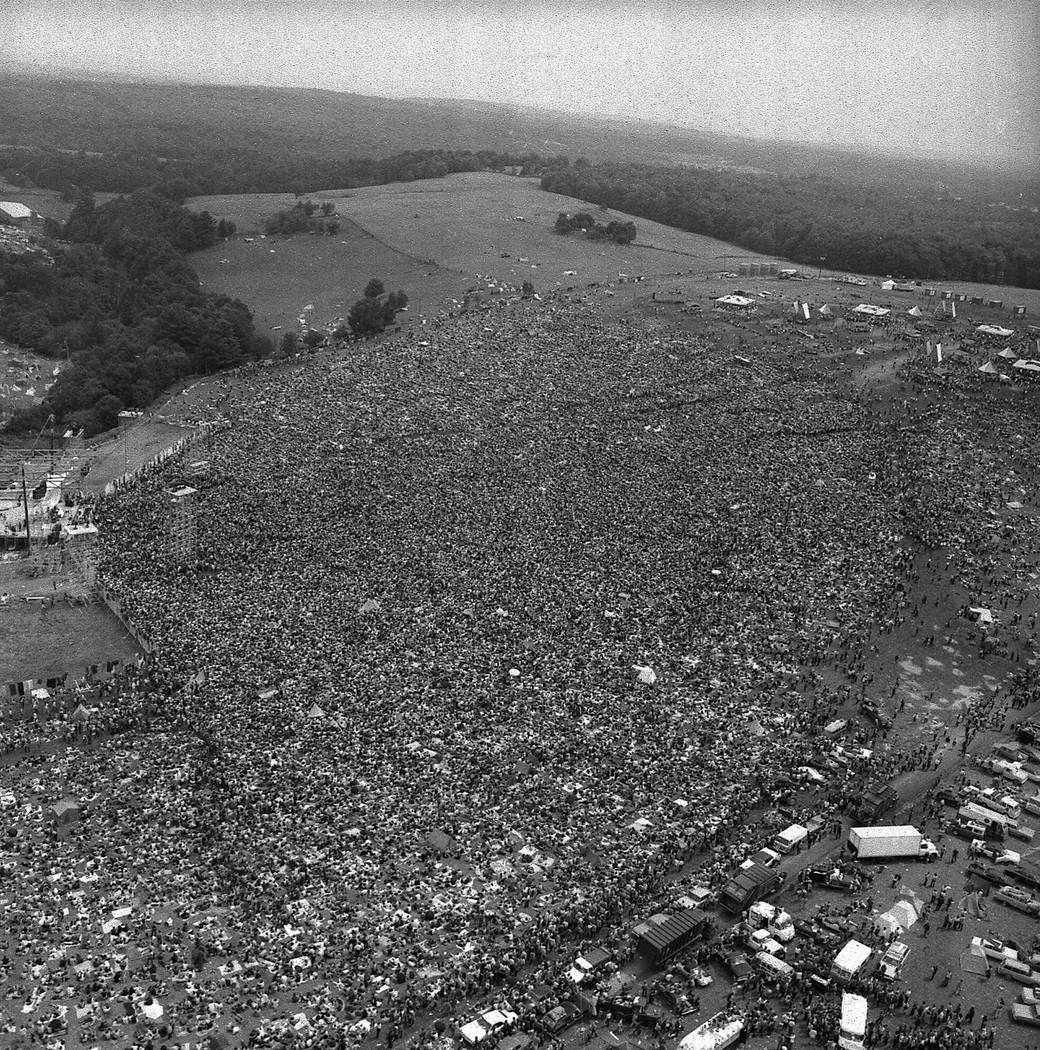

How did those masses look from above? “Like ants or termites or something,” the 74-year-old Fogerty recalls. “A zillion of them.”

So this was Woodstock.

Thursday, that marathon concert turned cultural touchstone turns 50, remaining a sign of the times whose legacy has endured even as those times have changed and changed again.

It made Carlos Santana and Joe Cocker stars, gave Jimi Hendrix a platform for one of the most electrifying performances of the “The Star-Spangled Banner,” proved that hundreds of thousands of longhairs and their straitlaced counterparts could come together peacefully while uniting a generation under the banner of rock ’n’ roll.

And it might not have happened the way it did if not for the man on the other end of the phone.

Woodstock’s 50th anniversary is being commemorated by a PBS special, a new book, a director’s cut of the now-iconic concert film, a 38-disc box set of recordings from the fest and more.

It’s also being celebrated by Fogerty himself. He’s been revisiting his band’s blistering Woodstock set during his “My 50 Year Trip” residency, which debuted in April and returns to Wynn Las Vegas in November.

About that night …

It was well past 1 a.m. on Sunday, Aug. 17, 1969, when Creedence took the stage.

Fogerty could barely see a thing.

“It was dark, and with the technology at the time, you could only see about two rows of people and then it was pitch black. They didn’t have the wonderful lighting that they do nowadays,” he recalls. “I looked down and I saw that basically everybody was all muddy, a lot them were naked, and they were asleep, rightfully.”

Blame it on the Grateful Dead.

Creedence was originally supposed to perform around 9 p.m., according to Fogerty.

But the Dead went long — way long — and even by the jam band’s own admission was far from its best.

“With the Grateful Dead having such a stilted performance, people just lost interest, and so I was basically playing to the darkness,” Fogerty says. “At some point, I actually went up to the microphone, because I thought we were playing great, and said something about, ‘Well, we’re playing our hearts out up here for ya. We just want you to have a good time.’

“And way out in the dark I could see somebody flicking his lighter,” he continues. “I hear a voice say, (in a far-off tone) ‘Don’t worry about it, John. We’re with ya!’ So I made up my mind, in front of all those people who I assumed were asleep, ‘I’m going to play the rest of the show for that guy.’ And that’s what I did.”

Because of the somnolent crowd, when Creedence was approached to be a part of the now-iconic “Woodstock” concert film, Fogerty passed.

“They sent me one song, just a reel-to-reel tape of ‘Bad Moon Rising,’ and said, ‘We’d like you to be in the movie and use this song,’ ” Fogerty says. “And we had such a problem — meaning that there was no reaction from the audience — I just felt that Creedence was hotter than a rocket everywhere else in the world, and I thought, ‘Why would I want to be in a movie that shows us struggling with a sleeping audience?’ So I declined at the time.”

Nevertheless, like Woodstock itself, Creedence’s performance would become the stuff of lore.

A hard happening to make happen

As detailed in the recently released book “Woodstock: 50 Years of Peace and Music” (Charlesbridge, $29.99), by author Daniel Bukszpan, it was a minor miracle that Woodstock happened at all given the organizational chaos and challenges that shrouded it from the start.

First off, Woodstock didn’t actually take place in the town of Woodstock, New York, but 50 miles away in the hamlet of Bethel, where a local dairy farmer named Max Yasgur rented out a portion of his land for $50,000. It was the festival’s third option.

From the get-go, there were serious logistical issues: As Woodstock’s opening day approached, organizers faced a dilemma: finish building the stage or the fencing around the festival grounds.

There simply wasn’t enough time for both.

“It was either bankruptcy or a riot,” Joel Rosenman, one of Woodstock’s promoters, told Newsday in 2009.

And with that, Woodstock became a free festival.

While there was no cost for fans, the same could not be said for the organizers: The day after Woodstock ended, they were $2.6 million in the hole. (That equates to more than $18 million when adjusted for inflation. The festival finally became profitable in the ’80s thanks to royalties from the concert film originally released in 1970.)

Attendees had their own challenges to contend with.

There were 1,500 Porta-Potties for 400,000 people, which translated to one toilet for every 267 concertgoers.

There was also a severe water and food shortage, with organizers struggling to find vendors to cater to such a large crowd — they inexplicably settled on Food for Love, a company with the right name but just three employees.

Some audience members grew so hungry, they risked their teeth by eating raw ears of corn from Yasgur’s fields.

Then there was the rain, which turned the site into one giant mud hole.

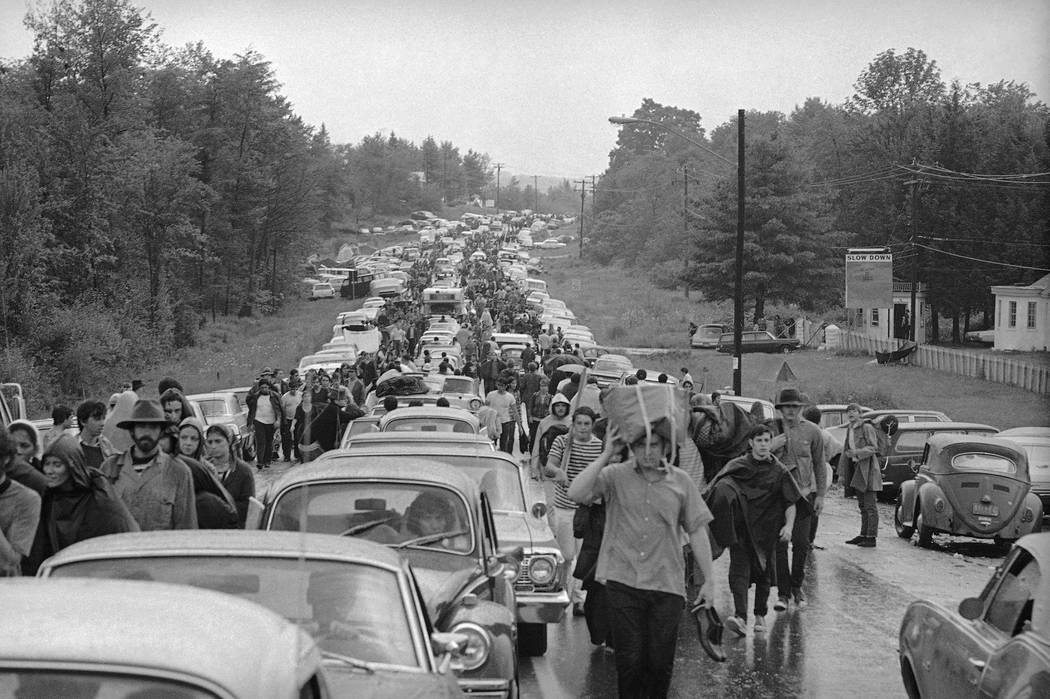

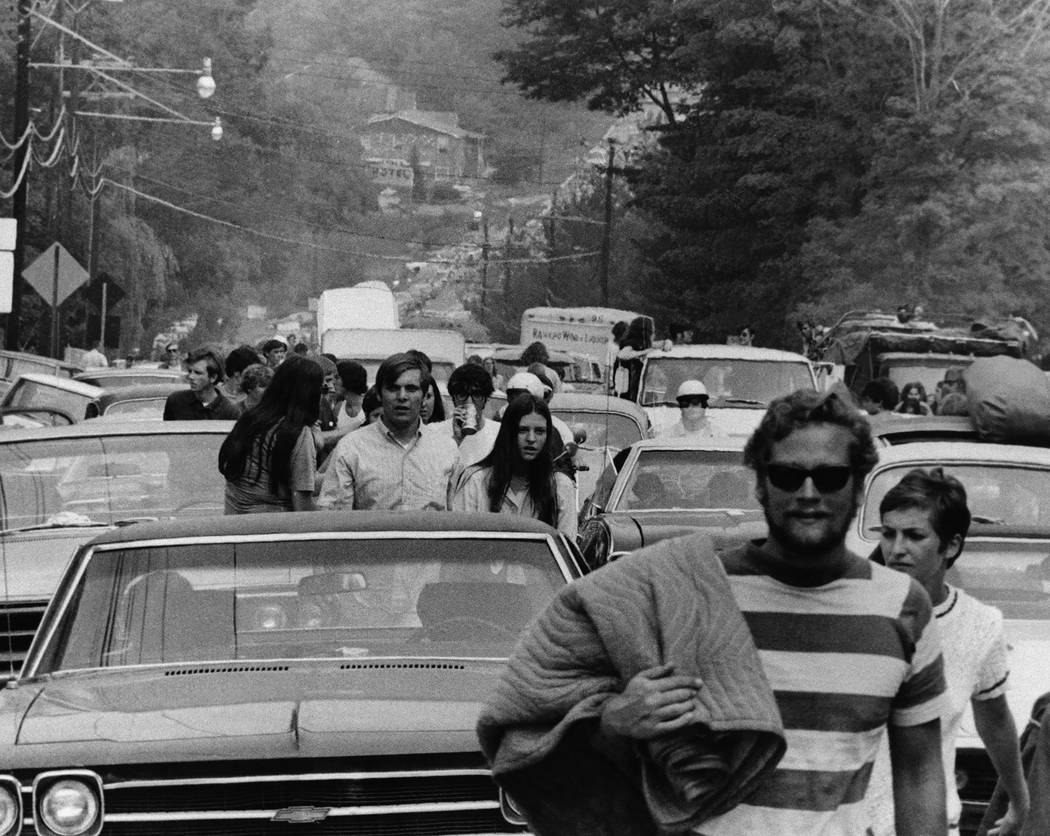

Even getting there was an incredible chore: Traffic was so congested, one nearby highway was backed up 17 miles at one point, elongating a 90-minute drive into an eight-hour trip.

Band aid

Assembling the festival’s lineup also was fraught with difficulties.

Fogerty recalls becoming aware of Woodstock in the spring of 1969 during some East Coast gigs.

“There were these billboards that said, ‘Come to Woodstock,’ and I said, ‘I wonder what that thing is?’ ” he remembers. “I’d go back to the Bay Area, and on the radio, they’d be talking about Jimi and Janis (Joplin) and the Who, stuff like that, so I just assumed all those people were already on board this thing called Woodstock.”

Fogerty says that he was contacted about Creedence playing Woodstock in June or July of that year, pretty late in the game, and thought the lineup was already full of big-name acts.

“But it turns out that when I said yes, Creedence was actually the first band to sign on for Woodstock,” Fogerty notes. “There’s actually a plaque on the wall at the Woodstock concert museum, it says, ‘After Creedence Clearwater signed on, then all the other bands decided it was OK,’ or something like that. That’s kind of what made Woodstock happen.”

But all these ups and downs don’t detract from Woodstock’s legacy.

Rather, they underscore the power of so many people coming together despite odds as long as the lines to the restrooms.

Beyond the music, this is ultimately what Woodstock represents, dirt beneath the fingernails and all.

“I will say, looking back, I was very proud of our generation,” Fogerty says. “I was very proud of the kids who went there and, under very severe conditions, managed to be polite and nice and civil. There was really no trouble, no incidents at all. They arrived peacefully, and left peacefully. I just thought that was pretty wonderful.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.