“Whew. I’m just about too pooped to pop.”

Even if he hadn’t admitted it, you could hear it in his voice. The young singer sounded about as worn down as a 21-year-old could be. Maybe it was the bright lights and late nights of Las Vegas. Perhaps it was having spent the past 13 days working to try to win over polite but skeptical audiences.

Clearly this wasn’t what Elvis Presley expected two weeks earlier, on April 23, 1956, when he made his Las Vegas debut at the New Frontier.

After all, “Heartbreak Hotel,” his first hit, and his eponymous first album were both about to top the charts, and he’d just signed his first movie contract with Paramount Pictures.

Having crisscrossed the South and parts of the Midwest over the past two years, leaving a trail of frenzied teenage girls in his wake, Elvis was welcomed to the New Frontier, his first nightclub-style venue, by a wall of indifference.

Sixty-five years later, it’s still regarded as one of the few missteps by his manager, Colonel Tom Parker.

But there was more to Elvis’ first taste of Las Vegas than many remember.

“What happened in Vegas with this two-week engagement,” says Angie Marchese, vice president of archives and exhibits for Elvis Presley Enterprises, “eventually is what elevated Elvis to another level.”

‘The Atomic Powered Singer’

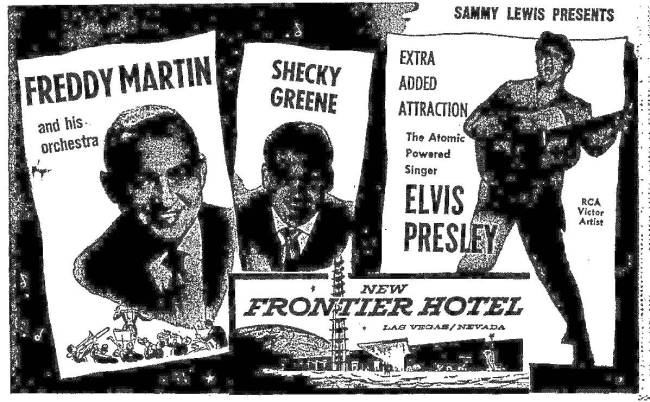

Comedian Shecky Greene and bandleader Freddy Martin and his orchestra were booked into the thousand-seat Venus Room, with the Venus Starlets dancers. The show promised a cast of 60 performers.

Ten days before the engagement, Parker negotiated a $15,000 deal for Elvis to join the bill for two weeks as “an extra added attraction,” during which he dubbed Elvis “The Atomic Powered Singer.”

A Review-Journal staff report April 20 announcing the engagement noted that Elvis had been “acclaimed by critics as the most important find since Johnnie Ray.” During personal appearances in California the previous week, “Elvis attracted turn away crowds of 5,000, and on two occasions special squads of police had to be called to maintain order among his admiring fans.” Sammy Lewis, the show’s producer, called it “one of the most lavish ever to be presented in Las Vegas.”

The hype failed to follow him to Nevada.

12 minutes to forget

“They were just three totally different personalities. No coherence to that show at all,” says Richard Zoglin, author of “Elvis in Vegas: How the King Reinvented the Las Vegas Show.” “It’s three totally different audiences. It doesn’t make much sense.”

Not only did Elvis not belong on the same bill as Martin’s big band, Greene admits, “I didn’t belong with Freddy Martin.”

Greene, who turned 95 this month, says he had no idea what an Elvis Presley was when the singer was added to the Venus Room lineup for daily shows at 8 p.m. and midnight. His first glimpse of Elvis was the two-story cutout Parker had placed in front of the New Frontier. It so overpowered his own name on the marquee, in Greene’s mind, that cutout was 75 feet tall.

The comic opened the show with the sort of raucous, largely unscripted act that would make him a must-see attraction in lounges up and down the Strip for years to come. Martin and his orchestra performed songs made famous by the likes of Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey before backing the Venus Starlets in a medley of highlights from the musical “Oklahoma!”

What followed was, by comparison, a lightning bolt of confusion.

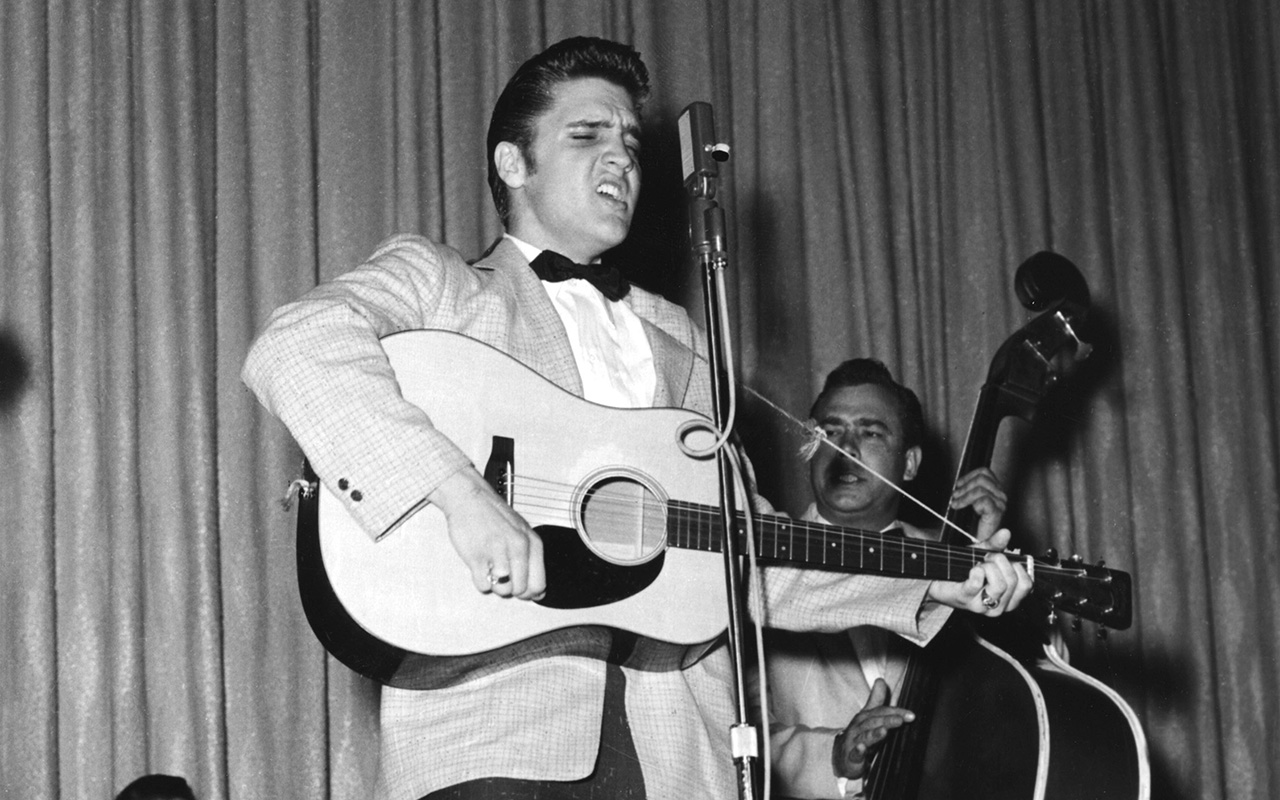

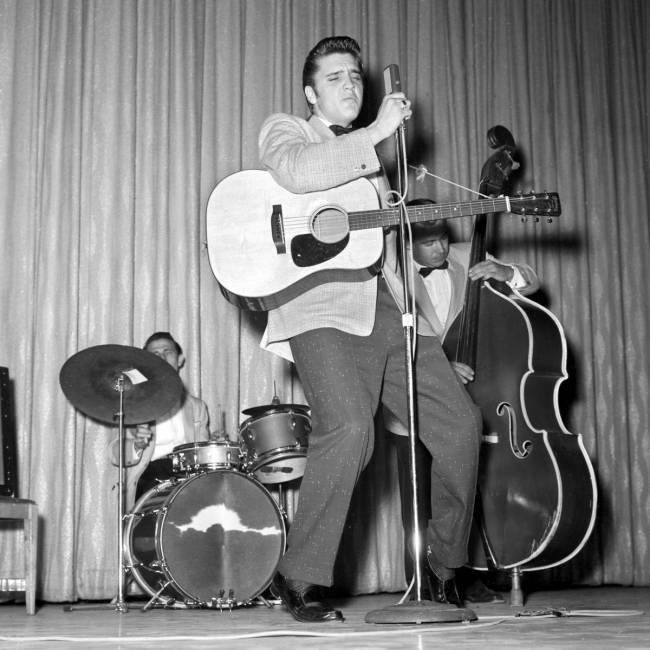

Elvis — with Scotty Moore on guitar, Bill Black on bass and D.J. Fontana on drums — took the stage in front of a plain curtain. Their four-song set — “Heartbreak Hotel,” “Long Tall Sally,” “Blue Suede Shoes” and “Money Honey” — came and went in 12 minutes before a dazed audience.

Trying everything

“From the first time he took the stage in Memphis (in the summer of 1954) until the time he took the stage in Vegas, every place he went, it was just screams,” Marchese says. “You couldn’t really even hear the music. It was all about the screaming girls. Getting on stage in Vegas, it was kind of a shock to his system because he didn’t get that feedback.”

The young performer wasn’t nearly experienced enough to successfully transition from a large musical production of “The Surrey With the Fringe on Top” to “Well, since my baby left me …”

“He was doing the same songs and doing the same gestures, and then all of a sudden not getting the same responses,” Marchese says. “It was kind of, like, ‘OK, am I doing something wrong? People aren’t reacting the way they normally do.’ Elvis didn’t know how to respond to that.”

There’s a touch of desperation in his voice in the sole audio evidence of those two weeks, taken from the “too pooped to pop” show on May 6, his final night. Elvis threw a little bit of everything at the Venus Room crowd.

He was self-deprecating, referring to his biggest hit to date, the one for which he’d received his first gold record the previous night on that stage, as “Heartburn Motel.”

Introducing “Money Honey,” he joked, “This song here’s really been a big seller for me. It’s sold 43 (copies).”

Another gag: “This song here is called, ‘Get Outta the Stables, Grandma, You’re Too Old to Be Horsin’ Around.’ ” Then he asked bandleader Martin, “You know that one about, ‘Take Back Your Golden Garter, My Leg Is Turning Green’?”

The most telling comment, though, came early on that evening.

“I’d like to tell you, it’s really been a pleasure being in Las Vegas,” Elvis said, full of sincerity. “This makes our second week here. Tonight’s our last night. We’ve had a pretty hard time, uh, had a pretty good time while we were here.”

Attack of the critics

Adding to his discomfort, there was an almost gleeful animosity in the reviews.

Bill Willard, the longtime local entertainment journalist who would later write for the Review-Journal, was pulling double duty as a columnist for the Las Vegas Sun and the Hollywood trade publication Daily Variety.

Covering that April 23 debut, Willard referred to the “brash, loud braying of his rhythm and blues catalog” and called Elvis’ sound “uncouth, matching to a great extent the lyric content of his nonsensical songs.”

The Review-Journal’s Les Devor dedicated the bulk of his April 25 Vegas Vagaries column to praising Martin and his orchestra. Elvis’ songs were dismissed as “shouting melodies,” though. “After the first number, the highly stylized delivery became repetitious,” Devor wrote, “and the similarity of his numbers was apparent.”

Newsweek famously said Elvis stood out in that environment like “a jug of corn liquor at a champagne party.”

“He was just such a different kind of performer, it was hard for those Vegas critics to sort of catch on to something that was really brand new, I guess,” Zoglin notes. “And maybe they were kind of defending sort of the traditional pop, Sinatra-style music against this rock ’n’ roll which, at that stage, was still almost thought of as music for juvenile delinquents. It was more of a cultural reaction than a musical reaction.”

After that first night, Elvis and Greene swapped places, with the young singer moving to the opening act. The consensus is that Las Vegas simply wasn’t ready for Elvis, but he may have found more success had he come a couple of years earlier.

In 1956, Las Vegas was transitioning out of its Old West past, Greene notes. The New Frontier had just reopened the previous year with a new name after an overhaul rid The Last Frontier of its Western theming and cowboy flair. At the time, the city was welcoming a lot of tourists from New York.

“Before then, it was all country and western. We had horses in the middle of the street,” Greene says. “But when (Elvis) came in, it had started to be a dressy crowd and everything. The Jews and the Italians, they didn’t know who the (expletive) Elvis Presley was.”

The teens respond

It would be easy to dismiss the New Frontier booking as nothing more than a misguided money grab.

According to Graceland’s Marchese, though, Parker knew exactly what he was doing. “Colonel had a plan all along. … It was about breaking Elvis out of that state fair, circus, teenage audience and actually giving him some credibility as an entertainer.”

With the ink still fresh on that movie contract, she says, Parker realized that if Elvis was going to make the transition to Hollywood leading man, he would have to broaden his appeal. The problem was, night after night of polite applause was beginning to diminish his swagger.

After that first week, Parker arranged for a 2 p.m. matinee concert at the New Frontier that teenage fans could attend. Admission was $1 and came with a soda. Parker, ever the opportunist, was in the lobby selling souvenir photos for 25 cents.

Unlike his four-song evening sets, the matinee was a full-blown Elvis concert in all his hip-swiveling, quiver-inducing glory.

“He went and got the kids, and you couldn’t get near the place on a Saturday afternoon,” Greene recalls from his home in Henderson. “We got the kids from the schools and everything else, and they jammed it.”

Proceeds from the show went to the Municipal Baseball Federation and the construction of the $35,000 lighted field, only the second in Las Vegas at the time, at what is now Ed Fountain Park.

“The matinee show for the teens was a last-minute effort to help make Elvis feel more comfortable about the bookings,” Marchese says. “He didn’t know if he could do it anymore.”

For that one afternoon, at least, teen heartthrob Elvis was back.

“The carnage was terrific. They pushed and shoved to get into the 1,000-seat room, and several hundred thwarted youngsters buzzed like angry hornets outside,” Robert Johnson reported in the pages of the Memphis Press-Scimitar. “After the show, bedlam! A laughing, shouting, idolatrous mob swarmed him; he fled to the insufficient sanctuary of his suite.”

One woman, who Johnson reported “had been bowled over in the teenage tidal wave,” couldn’t believe the commotion. “ ‘My gawd, what those kids did to the ladies room! Lipstick all over the walls … baskets turned over and the paper strewn around … it looked like a wrecking crew just finished.’ ”

Dressing the part

Beyond his missing mojo, Elvis also found a sense of style.

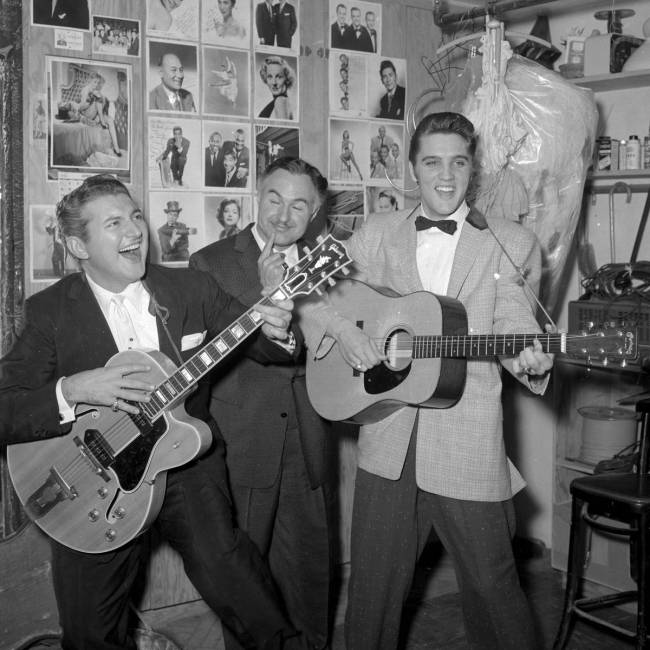

“Elvis Presley came in with these three guys, and they were wearing baseball jackets,” Greene says of that first show. He knew Parker from their days working in New Orleans and pulled him aside.

“I said, ‘Tom, he can’t come out like that. In a baseball jacket?’ ‘Well, whaddya mean he can’t come out like that?’ ” Greene says, slipping into an impression of Parker. “ ‘He works all over that way, Shecky.’ ”

The next night, Elvis and his band were dressed more appropriately for the showroom. On May 10, four days after his New Frontier finale, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune advanced his upcoming shows in the Twin Cities by noting that “Presley recently bought himself 45 fancy sport shirts, as well as 30 suits.”

A signature find

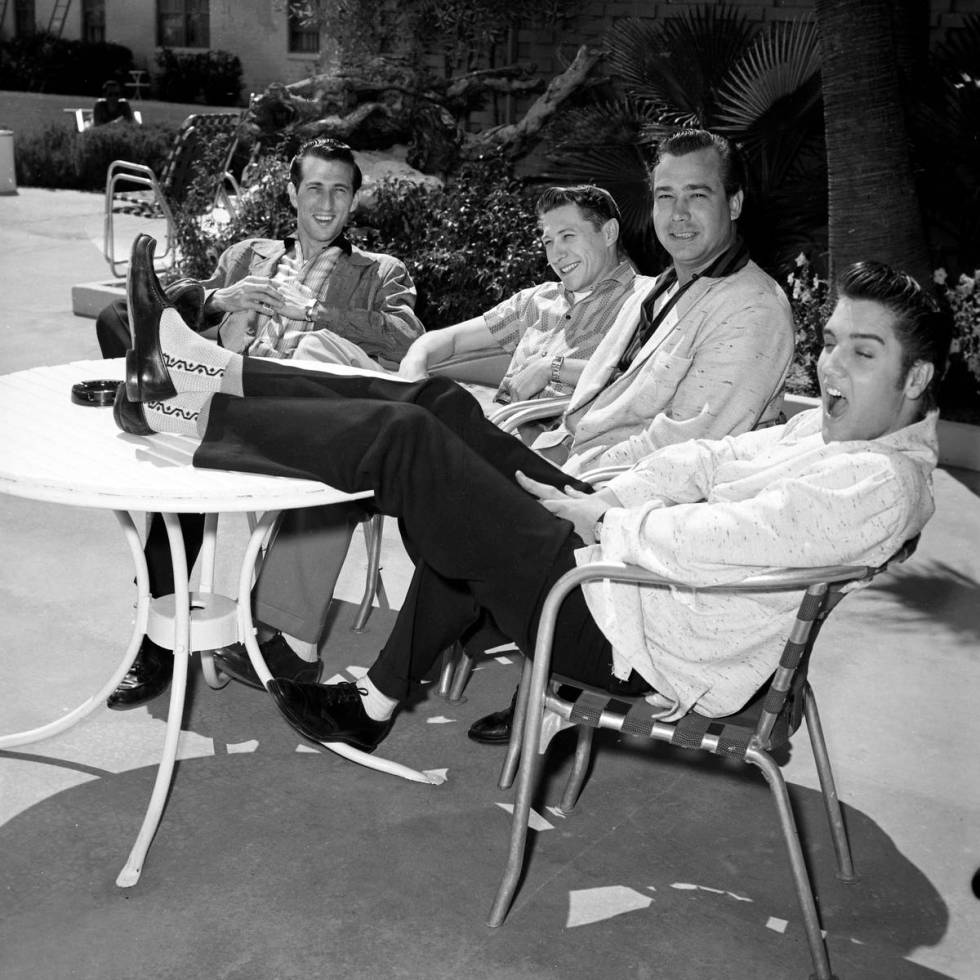

The biggest discovery of that week, though, came during a night out at the Sands Cocktail Lounge.

“He loved show business,” author Zoglin says, “and he loved that he could just go from hotel to hotel and see lounge shows and see (different) performers.”

Before arriving in Las Vegas, Elvis had only performed in the same city on consecutive nights twice that year. He had adopted a grueling schedule of playing up to four times a day, then moving on to the next town. The two 12-minute performances a day at the New Frontier left him with plenty of free time.

Elvis didn’t drink, and he didn’t gamble. That left going to the movies, spending time at the Last Frontier Village theme park next door — he spent five hours driving bumper cars there one day, we reported — and seeing other acts, including The Four Lads, who were making their Las Vegas debut at the Thunderbird, and Johnnie Ray, to whom he had been compared, at Wilbur Clark’s Desert Inn.

At the Sands, he and his bandmates first laid eyes on Freddie Bell and His Bell Boys. As part of their popular lounge act, they performed an updated version of a song that had been a hit a few years prior for Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton. Bell had changed the Jerry Leiber-Mike Stoller lyrics, removing the sexual innuendo, and turned “Hound Dog” into a song about an actual canine.

“We always like to say Elvis put his twist on things,” Marchese says of the version, not quite Bell’s and certainly not Thornton’s, he released two months later that would go on to become one of his signature songs.

His second home

As soon as Elvis returned to Memphis, he stopped by the Press-Scimitar offices to say how much he enjoyed Las Vegas and that he couldn’t wait to return. He would, often, even if it was just for the weekend while he was filming a movie in California, Marchese says. Elvis was back that November and made time to buy that year’s first batch of Christmas Seals while encouraging Las Vegans to help aid the fight against tuberculosis.

“I think it was the freedom that he felt in Las Vegas,” Marchese says of what drew him to the city. “Being able to relax. Being able to go hang out by the pool or go see other artists. That whole vibe of Las Vegas is what he loved.”

If nothing else, the love affair with the city he developed over those two weeks helped pave the way for his record-setting engagements in 1969 at what was then the International Hotel.

“I don’t think the gig did a lot for him musically,” Zoglin says of the New Frontier. “He did those four songs. It didn’t sort of advance him at all in terms of his music. I think that the main effect was just that he loved Vegas. … That became sort of a second home for him, so that when the time came, a decade and a half later, to make the comeback, he was very comfortable there.”

It was Elvis’ return to live performances after his years in Hollywood, and the seven-year run of sold-out shows that followed, that made the singer synonymous with Las Vegas.

And, of course, the same type of tourist who didn’t know what to make of him in 1956 turned out in droves.

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567. Follow @life_onthecouch on Twitter.

Teen was not 'All Shook Up'

Nancy Heberlee remembers seeing the flyers for Elvis Presley's matinee up and down Fremont Street, where teenagers tended to cruise in 1956.

Heberlee, a 17-year-old senior at Las Vegas High School that spring, was at the New Frontier that afternoon, but she didn't bother attending the show. Her father was a dealer there, and he had gotten permission for her to go swimming.

While Heberlee was sunning with her 4-year-old brother, Elvis came out and began posing for some publicity photos around the pool. She noticed — and quite vividly recalls just how unbuttoned his shirt was — but didn't pay her fellow native Mississippian much attention.

"I grew up with guitar players. I'd never heard of him. I just had no interest," Heberlee, now 82, says. She had relocated from The Magnolia State just two years before.

"So Colonel (Tom) Parker came up, and he said, 'Would you like to meet Elvis?' And I just kinda laid there and said, 'No, I don't think so,' " Heberlee recalls, a loud laugh escaping her. Parker backed away and moved on.

"It's strange now," she says, recalling that near encounter. "I mean, hindsight's always better than in the moment."