Moviegoers in the 1970s were a hardy bunch.

They’d already weathered nightmares involving sharks, Linda Blair’s spinning head and Ned Beatty’s misadventures in the Georgia woods.

Then, in 1978, came “Midnight Express,” a movie so harrowing that the words “Turkish prison” still have the power to terrify.

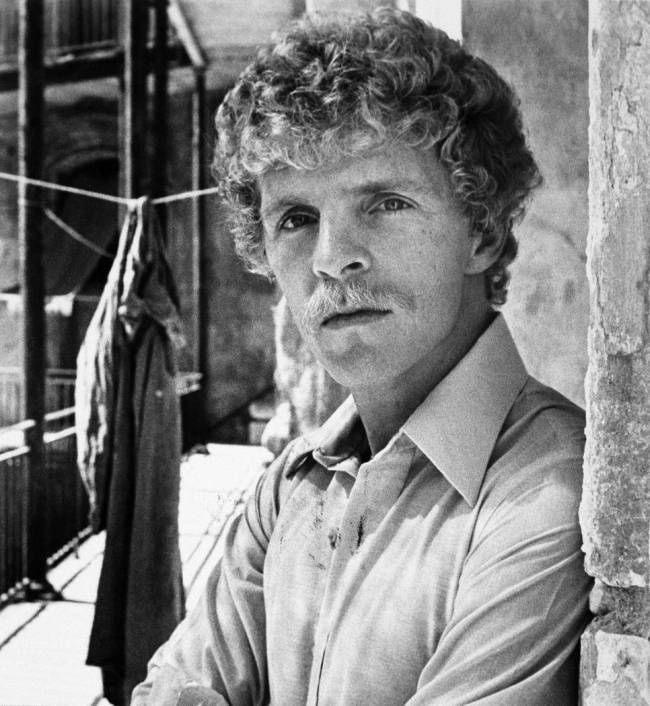

No one knows those horrors, though, better than Billy Hayes.

On Oct. 6, 1970, the current Summerlin resident tried to board a flight from Istanbul to his native New York with two kilos of hashish taped to his torso. He spent the next five years in a variety of prisons around Turkey before escaping, flying home to see his family and chronicling his ordeal in the book that inspired the landmark film.

“Most guys want to forget prison,” Hayes, 72, says over coffee and a muffin. “I never had that opportunity and probably am glad I didn’t. It was so therapeutic to start talking when I got off the plane, and I never stopped.”

Far from the sweaty, conspicuous mess portrayed in the movie by Brad Davis, by the time the real Hayes approached that Istanbul customs agent, he’d already made three successful smuggling runs.

“It was exciting. It’s what I loved most,” he says of those trips.

“I wanted to do all this so I could write about it. I thought of myself as this adventurer. I was such a (expletive) idiot.”

Hayes was studying journalism at Marquette University in Wisconsin while working at a hospital when a friend came back from Turkey with a small piece of hash. Soon after, wandering the hospital’s halls during a break, Hayes saw a doctor applying a cast and something clicked.

“I thought ‘Hash. Cast. Istanbul. What a great idea!’ ”

Two weeks later, in April 1969, he was in the Turkish city, having been staked by several of his friends, taping two kilos to his leg and wrapping that appendage in plaster before clomping back to the U.S.

Hayes had his fill of the drug and pocketed about $5,000 — more than $35,000 in today’s money. He went back every six months or so and grew more confident — and more careless — with each successful crossing.

“I seriously thought I was way too smart and good-looking to ever get arrested,” he admits.

Before his fourth flight home, Hayes watched passengers go through customs, as he always did. He’d planned to go to the observation deck to witness them board the plane, but he got distracted by a woman — a belly dancer no less.

Had he followed through, he would have seen soldiers searching passengers on the tarmac.

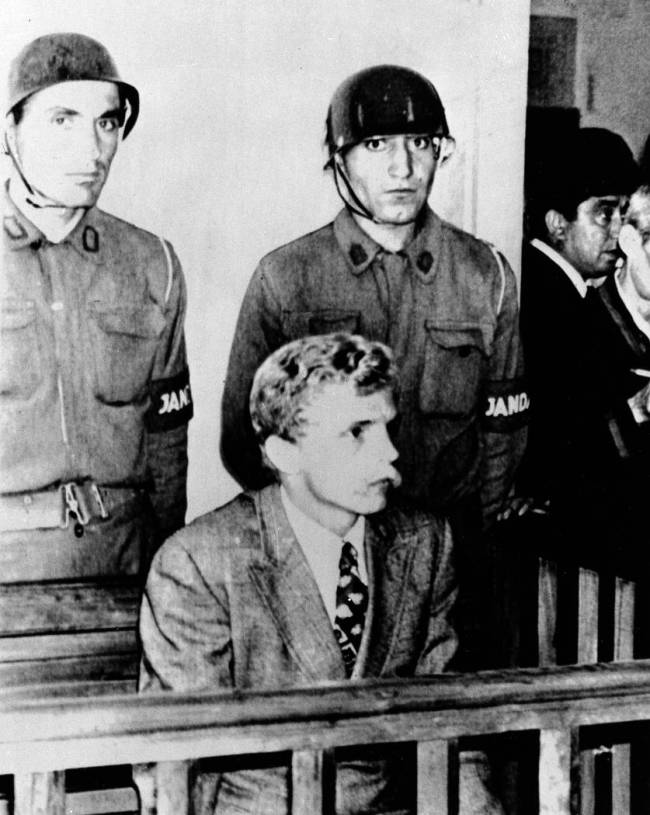

“My first reaction was, ‘This can’t be happening,’ ” Hayes says of his arrest. “I denied reality. ‘This can’t be happening to me’ — while it was happening. That’s how stupid I was.”

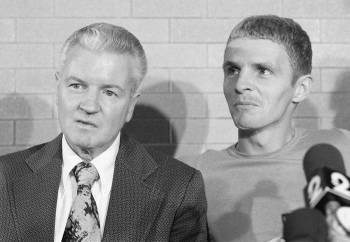

Once Hayes completed his memoir, also titled “Midnight Express,” with author William Hoffer, he spent about a week holed up in New York’s Mayfair Hotel discussing his various traumas with a fledgling screenwriter named Oliver Stone.

Among the liberties Stone took with the script, Hayes never killed a guard. His actual escape — involving a stolen boat, miles of rowing, evading landmines and swimming across the Maritsa River into Greece — was far more adventurous. It also would have been far more expensive and time-consuming to film.

Hayes is most angered by the scene in which he’s being resentenced for his crime. He was weeks away from completing his 50-month stint for possession when he was sentenced to life — later lowered to 30 years — for smuggling. In the film, Hayes explodes, screaming at the judge that Turkey is a nation of pigs.

Those words would have repercussions for decades.

“Nobody would say that,” Hayes vents now. “That’s so stupid. The illogic of that pissed me off.”

“Midnight Express” would go on to become a phenomenon.

Hayes and his story were among the toasts of the 1978 Cannes Film Festival, where he met Wendy West, his wife of 39 years.

When the 1979 Academy Awards rolled around, the movie garnered six nominations, including best picture. It lost the big prize to “The Deer Hunter” but took home trophies for Stone’s screenplay and Giorgio Moroder’s synth-heavy score.

It didn’t take long for “Midnight Express” to become a mainstay of popular culture.

In 2000, his story was choreographed as a ballet that was revived 13 years later in London.

The movie has been jokingly referenced in everything from “Entourage,” “The Simpsons” and “Gilmore Girls” to Jim Carrey’s manic, nipple-baring performance in “The Cable Guy.”

Among the many questions “Airplane!” star Peter Graves asks his young cockpit visitor: “Joey, have you ever been in a Turkish prison?”

“I love that!” Hayes says of that 1980 comedy, despite the painful memories. “It’s funny to me.”

Not everyone, though, was a fan of “Midnight Express.”

In keeping with Hayes’ memoir, the main guard, Hamidou (Paul L. Smith), was portrayed as a sadist. But there wasn’t a redeeming Turk — not even Hayes’ lawyer — to be found anywhere in the film.

It’s a far cry from the real experiences of the man who loved Istanbul and had several friends, even a girlfriend, there. For his own legal protection, though, he was unable to speak about his other visits to Turkey for years. Whenever he was asked how many trips he made to Istanbul, he answered: “One trip too many.”

Once the film entered the public conscience, the idea of landing in a Turkish prison became so frightening, many travelers assumed the best way to stay out of one was to stay out of Turkey altogether.

“Turkey’s tourism dropped 95 percent when the movie came out,” Hayes says. “To this day, until I went there and sort of balanced the scale, they thought I killed a guard and cursed out the nation.”

In 2005, Hayes began trying to revisit Turkey to make amends for the unintentional damage he inflicted. His visa was repeatedly rejected until, in 2007, the Turkish National Police invited him to speak at a conference in Istanbul. That trip is chronicled in the 2016 documentary “Midnight Return: The Story of Billy Hayes and Turkey,” which not only earned Hayes a sense of closure, it brought him back to Cannes.

This fall will mark the 50th anniversary of Hayes’ arrest, and the closest thing to a steady profession he’s had in the ensuing years is being Billy Hayes from “Midnight Express.”

“I tried to get away from it,” he admits. “My first Screen Actors Guild card was ‘William Hayes.’ I needed to get away from all that Billy Hayes, ‘Midnight Express’ (expletive) and just get accepted for who I am and what I’m doing. I quickly realized, no one knows who the (expletive) William Hayes is. Billy Hayes? That’ll get me in any door in Hollywood.”

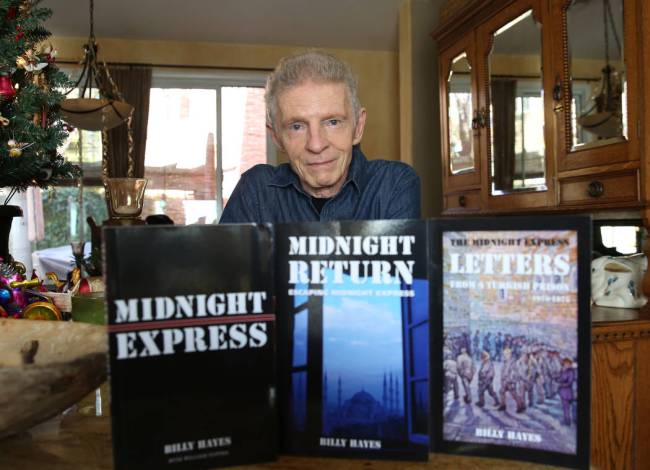

In addition to “Midnight Express,” he’s authored the books “Midnight Return: Escaping Midnight Express” and “The Midnight Express Letters: From a Turkish Prison 1970-1975.”

He’s played a mutant in Roger Corman’s 1980 sci-fi spectacle “Battle Beyond the Stars” and was machine-gunned to death by Charles Bronson in 1987’s “Assassination.”

Hayes has been involved in a couple of dozen theater projects, as an actor and director. The most meaningful of those being his one-man show, “Riding the Midnight Express With Billy Hayes.”

After launching it at the 2013 Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Hayes has performed it off-Broadway and in London. He’s taken it to Australia and Beirut. Now, after a one-off show here in August, he’s hoping to find a home for it in Las Vegas.

Hayes and West relocated to Las Vegas in 2014, right in the heart of touring the world with his show. Some friends had moved here and liked it. After several decades, Hayes needed to get away from the stress of Los Angeles and its traffic. “I had to smoke a pipe and do some yoga,” he says, “just to drive to the store.”

Undeterred by his arrest, Hayes remains a cannabis advocate. The only thing surprising about his upcoming line of CBD pre-rolls, under the name Midnight Express: Find Your Freedom, is that it took him this long.

“I wish Dad was here,” he says of the late William Hayes Sr. “His face would be, just, ‘You’re doing what? Haven’t you learned anything?’ Yes. I’ve learned, ‘Do it when it’s legal.’ ”

Hayes earned some very good money from “Midnight Express” in its early days, and he still gets a check in the low five figures from Columbia Pictures each year. Still, he has high hopes for the CBD line.

“I make money in clumps and bunches. I never know (after) the last clump when the next bunch is going to come in,” he admits. “I want to give my wife a little bit more security to know we have a steady income.”

During a nearly two-hour conversation, Hayes gets lost in his stories a few times.

To be fair, he’ll turn 73 in April, and he spent five years in unspeakable conditions, some of it in the rudimentary Bakirkoy Psychiatric Hospital in Turkey.

“I’ve had handcuffs on. Handcuffs are nasty,” he says at one point, with no prodding. “Chains? There’s a whole different feel when they chain you. That brings back some deep, I dunno what, but I don’t like chains at all. I didn’t like getting tied and beaten, either.”

He endured so much during his incarceration — including falaka, the ritual of a guard using a stick to wail on the soles of a prisoner’s feet — that the thing Billy Hayes says scares him the most comes as a surprise.

“My biggest fear is being irrelevant. That nobody gives a (expletive), that nobody remembers, nobody cares. That’s my biggest fear.

“But I discovered that they do care. In fact, they love this story. And it’s so good for me to keep telling this story.”

This story first appeared in the inaugural Spring 2020 issue of rjmagazine, a new quarterly published inside the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

Read the rest of the Spring 2020 issue here.