‘It shouldn’t have ended’: New doc captures the ’90s heyday of Maryland Parkway

It may be hard to imagine now, but during the ’90s, Maryland Parkway was the center of alternative culture in Las Vegas.

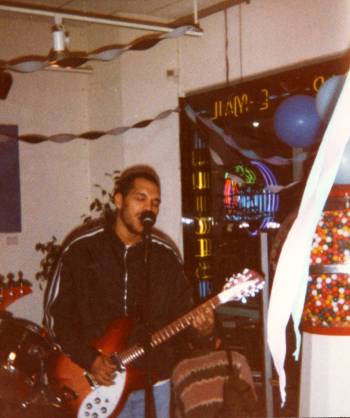

There, over a few blocks anchored around the UNLV campus, poets and artists presented their work to audiences, alternative bands and performers found new fans, and music lovers bought records available nowhere else in town. Las Vegans inclined toward entertainment not found on the Strip mingled, indulged their own creative leanings, created culture and drank copious amounts of coffee while KUNV-FM, then considered among the best college radio stations in the country, provided the soundtrack.

But magic seldom lasts, even in Las Vegas. By the early 2000s, the idiosyncratic shops and gathering spots began to close, artists and patrons moved elsewhere and, to add insult to injury, KUNV had canceled “Rock Avenue,” its signature alternative music showcase.

Writer/artist/filmmaker Pj Perez was a habitue of the Maryland Parkway scene in those days. In his new documentary, “Parkway of Broken Dreams,” he explores Maryland Parkway’s too-brief cultural heyday.

The film will have its premiere Wednesday at Galaxy Theatres Boulevard Mall. The event begins at 8 p.m. and will include a Q&A with Perez. Tickets are $15 (parkwayofbrokendreams.com).

A cultural confluence

The short but memorable life of Maryland Parkway as a cultural keystone grew, pretty much organically, out of a fortunate collection of factors.

“I think part of why it was even possible that it happened at that time is because there were circumstances that were unique to that time period,” says Perez, who now lives in Orange County, California. Chief among them: “It was pre-internet, so the only way you could get music and community engagement was in person, and where do you go to in person to find those cultural touch points? Record stores, coffee shops and bars.”

Maryland Parkway had them all in a span of just a few blocks. Tower Records and Benway Bop, an independent record shop where bands sometimes would play. Cafe Copioh and Cafe Espresso Roma, where poets and performers, and interesting friends and strangers, always could be found. Even, Perez recalls, a Kinko’s copy center where fliers for shows by local bands could be printed at a discount after midnight.

Maryland Parkway also emerged as culture focal point because the Strip at the time offered few entertainment options for young people, Perez says. Nightclubs hadn’t yet come to the Strip, giving young people “no place else to go,” and Maryland Parkway merchants “already had a captive audience of college students.”

Then, by the early 2000s, the Maryland Parkway cultural scene ”dissipated for a variety of factors,” Perez says. “A big one was a change of culture to online.”

Visual history

“Parkway of Broken Dreams” is a cinematic extension of an oral history of Maryland Parkway that Perez wrote for the Las Vegas Weekly in 2006. Two years earlier, UNLV had unveiled a plan to create a cultural corridor around the university, including along Maryland Parkway.

It sounded familiar to Perez. “Ten years earlier we had already accomplished that,” he says. “I was like, ‘Someone’s got to tell the story.’ ”

The Weekly story was “a direct reaction to that,” says Perez, and the documentary now expands on it. Over about 18 months, Perez filmed interviews with more than two dozen people who helped create the scene and were players in it.

Amazingly, there was no great master plan to turn the stretch of Maryland Parkway, roughly between the Boulevard Mall and Tropicana Avenue, into an alternative culture hot spot.

“The weird thing is, it’s one of those things where people who were involved in it at the time didn’t talk about it,” Perez says, even if “you kind of felt that this is special.

“You were just doing it. ‘All right, we’re going to put on this show at the coffee shop, we’re going to have a rave in the back of this record store, we’re going to throw some art up on the walls.’ It wasn’t, ‘Oh, I heard that my friend had a great experience at this coffee shop so I’m going to open a record store.’ It was none of that.”

Creating a cultural legacy

The welcoming alternative culture of Maryland Parkway would come to serve as a starting point for where culture in Las Vegas would go next and provided a training grounds for creators of that culture.

“One of the challenges I had making this film was … there were so many influential people who went on to do huge things,” Perez says. KUNV DJs moved into music business careers. People who threw after-hours events on Maryland Parkway became nightlife industry bigwigs. Ken Jordan, co-founder of The Crystal Method, was a KUNV DJ. The Killers played some of their earliest shows at Cafe Espresso Roma, Perez says, and “CSI” creator Anthony Zuiker “used to hang out at (Cafe Espresso) Roma. That’s where people hung out to write.”

Cafe Espresso Roma also hosted Poetry Alive, a popular open mic series. Writer/attorney Dayvid Figler discovered it while, he recalls in the film, “looking specifically for open mic poetry places that would let me do my brand of non-poetry poetry, which was just designed for laughs.”

In the film, he recalls seeing fewer than a dozen audience members at readings in 1991 until, in 1993 or 1994, “there was just no space for people in the poetry readings. It was wall-to-wall kids sitting on the floor, legs crossed, sitting on top of tables, sitting on top of the counter. It was really (a) full house, fire code-violating full house.”

“Poetry Alive was the first thing I stumbled upon on Maryland Parkway, and I was thrilled,” poet Dena Rash Guzman recalls in the film. “I didn’t know that you could go to a poetry reading outside of a boring university one. I didn’t know that you could sit there like a beatnik and look at other beatniks, and there was this tension and yet this creativity all in one room.”

A more ephemeral but vital player in the scene was KUNV-FM, UNLV’s radio station, primarily through its signature alternative music showcase, “Rock Avenue.”

“You don’t think of (a radio station) as a physical thing, but it was a physical thing,” Perez says. “People would go across the street to the Student Union and you’d just go to the studio and hang out.”

KUNV “was huge,” he says, and the 1998 cancellation of “Rock Avenue” was a sign that the scene was changing.

“A lot of people talk about this in the film,” Perez says. “You felt the impact right away. You had people hearing (music) on the radio, then you went to find music in the record store, then you’d go to the record store and find out, ‘Oh, this artist coming to the Huntridge Theater.’ ”

The end

“In theory, it shouldn’t have ended, because across the street was a major university and it was growing,” Perez says. “You’d think there’s always going to be students hanging out at coffee shops. But there was such a change of culture going on in the late ’90s to the early 2000s.

“You’re already starting to see it in the scene on Maryland Parkway. You see that it’s starting to dissipate a little bit. It takes several years to happen, but you could already feel it then. It’s hard to say why.”

Alternative music went mainstream. Social media began to replace socializing. UNLV remained a primarily commuter campus. Businesses closed. First Friday kicked off downtown. And, as they do, culture seekers began to search for something new.

Ultimately, Perez says, “it was a matter of bodies shifting from one place to another, and (Maryland Parkway) couldn’t sustain the bodies shifting.”

In addition to offering a glimpse into what may be a less-remembered bit of Las Vegas’ cultural history, “Parkway of Broken Dreams” underscores, first, “the importance of institutional or municipal support” for such cultural resources to help “people who have a vision for small businesses who may not have the means to sustain a business,” Perez says.

But, he says, “really, I’d have to say the takeaway is not realizing what you have until it’s gone. I think we took for granted these things will always be there in one way or another.”

It was “a unique and special time and place I haven’t experienced since,” he says. “You keep hearing people use the word ‘special.’ ‘Magical’ is the other one that keeps coming up.”

People even now “talk about the effect that era had on their lives” and “the lifelong friendships that came out of it,” says Perez, who likens the Maryland Parkway scene to the bonding that can occur in college.

“Some of these people went to college,” he says, “but their university experience was four years of Maryland Parkway.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.