Love him or loathe him, Elvis manager Colonel Tom Parker was good for Vegas

Colonel Tom Parker was a once-in-a-lifetime mastermind who saw the winds of change blowing through America in the mid-1950s, took a truck driver from Tupelo, Mississippi, under his wing and, in just a few months, molded him into the biggest star on the planet.

Colonel Tom Parker was a carny huckster who latched onto a 20-year-old Elvis Presley, pocketed up to half of his income, refused to let him grow as an artist, and way past the point when the bloated and drug-addled singer should have been in rehab, kept him trapped in a grueling tour schedule that only ended when he died.

Both of those sentences can — and may — be true. The real Parker, though, likely fell somewhere in between.

“I, too, had heard all the stories about Colonel and was a little hesitant before I met him, but he put those (concerns) to rest right away,” says Wayne Newton, a close friend to Presley who became one to Parker. “I remember hearing the stories of (people) bringing a script to him and saying, ‘This is a movie we want Elvis to do, and we’ll pay a million dollars.’ And him saying, ‘Well, that’s good for me. Now, what are you gonna give Elvis?’ … You wonder how much of that was made up.”

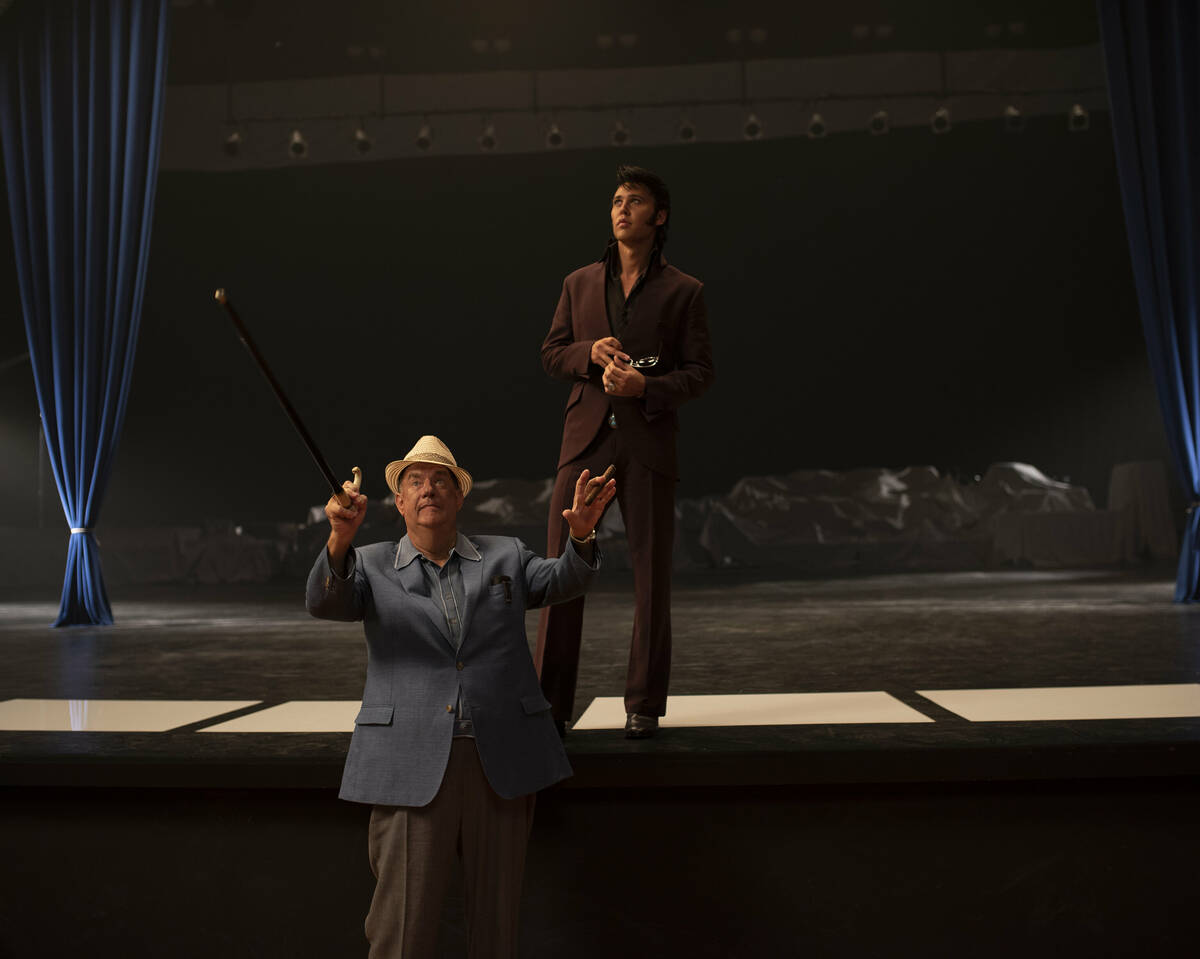

Starting Thursday evening when “Elvis” debuts in theaters, with Tom Hanks portraying Parker, moviegoers can join the decadeslong debate over his treatment of the superstar with whom he’d become inextricably linked.

There’s little denying, though, that Parker, who maintained a residence here from 1969 until his death in 1997, was very good for Las Vegas.

Shrouded in mystery

First, some backstory.

Colonel Tom Parker, as “Elvis” director and co-writer Baz Luhrmann likes to say, “was never a Colonel, never a Tom and not even a Parker.”

Born June 26, 1909, in Breda, Holland — not Huntington, West Virginia, as he claimed — a young Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk is believed to have taken the name “Tom Parker” from a soldier he met during his two-year stint in the U.S. Army. The honorary title of colonel in the Louisiana State Militia was bestowed upon him in 1948 by governor and former country singer Jimmie Davis. It was a made-up rank in an organization that didn’t exist at the time, but Parker seized on it nonetheless.

After the Army, Parker worked the carnival circuit, where it’s said — so much of his life is shrouded in mystery and partial truths that even those who knew him best disagree on some of this — he made ends meet by painting sparrows yellow and selling them as canaries and by exhibiting “dancing chickens,” which meant placing live chickens on a hot plate, causing them to jump around.

He eventually turned to music, managing singers Eddy Arnold and Hank Snow before being introduced to Presley on Feb. 6, 1955, between shows at Memphis’ Ellis Auditorium. Parker became the singer’s sole representative, and Presley became his final client, the following year on March 15.

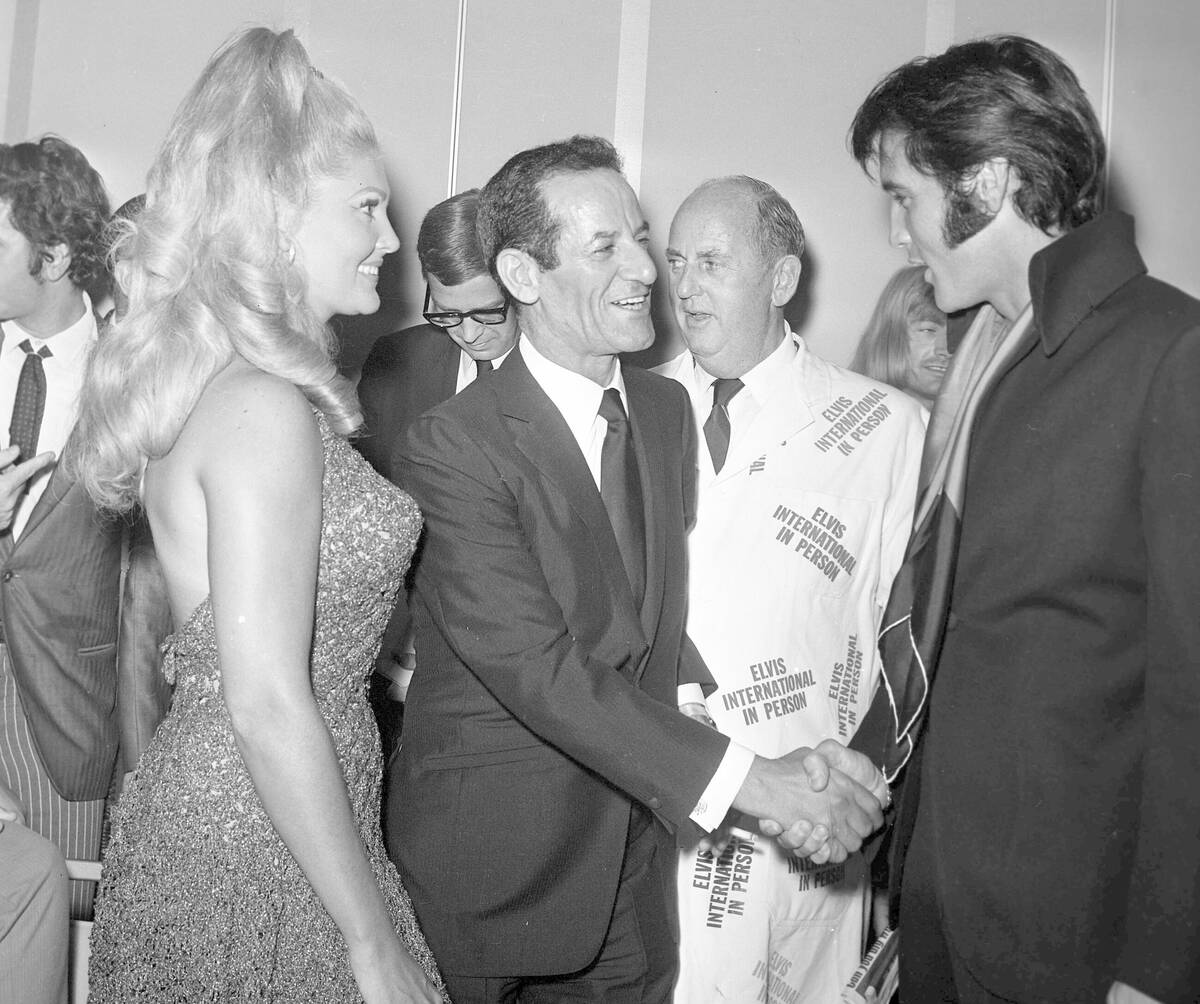

Five weeks later, on April 23, 1956, Presley made his Las Vegas debut with the first of two weeks of shows at the New Frontier.

He wouldn’t return to a Las Vegas stage until July 31, 1969, when he played the first of 57 shows over the next month at the International Hotel. They were his first ticketed performances since a benefit concert in Pearl Harbor for the USS Arizona Memorial more than eight years before.

Presley would go on to perform at the International and the Las Vegas Hilton as it was soon renamed — it’s now the Westgate — two shows a night for a month at a time, twice a year, through 1973. Shorter stints followed each year until his final local show on Dec. 12, 1976.

Like CES twice a year

You simply can’t overstate the financial impact of Presley’s run at the International/Hilton.

“He would attract well over 100,000 people twice a year,” the hotel’s publicity executive Bruce Banke said in a Review-Journal story announcing Parker’s death. He compared the economic impact of each of those monthlong residencies to that of CES. “An Elvis engagement in Las Vegas was fantastic for the entire town, because naturally all those people couldn’t stay at the Hilton.”

Banke, who died in 2000, described the atmosphere surrounding those shows as part of a 1987 retrospective.

“An Elvis engagement was absolutely like the old days when the carnival was coming to town. The Colonel would decorate the hotel from top to bottom,” he recalled. “One September, he bought virtually half the billboards in town — during an election year. You had to know Elvis was in town — unless you came in by tunnel.”

Review-Journal entertainment columnist Forrest Duke was wowed by Parker’s advertising spend in 1971, noting “nearly 150 billboards and bus benches, plus saturation campaigns on every Las Vegas radio station.”

That column appeared beside a three-quarter-page advertisement for the shows.

Newton looks back

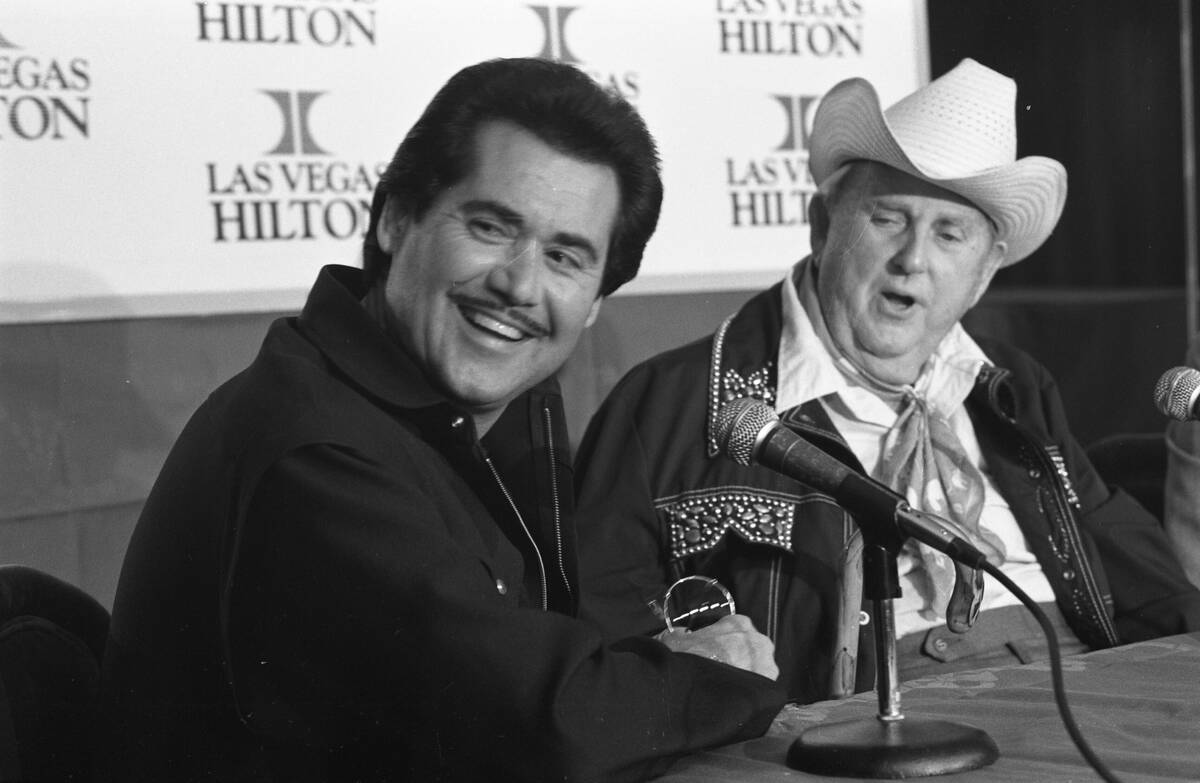

Parker remained a consultant for the Hilton throughout his life but, following Presley’s death on Aug. 16, 1977, he would promote just one more show. In 1987, he approached Wayne Newton backstage at the Hilton where he was headlining at the time and asked him to perform a series of tribute shows.

The singers had been friends since 1966 when they met on the Paramount lot. Newton was guest-starring on “Bonanza,” studying his script on set, when he felt a tap on his shoulder. He turned to see Presley, who was on a break from filming a movie next door.

Newton was rambling about what a big fan he was when Presley interrupted to ask if he knew a young lady named Sandy Ferra. “I paused, and I said, ‘Well, yes. As a matter of fact, we’re dating,’ ” Newton recalls. “And he said, ‘So are we.’ ” They laughed and became what Newton calls “instantaneous friends.” (Ferra would go on to marry disc jockey and game show host Wink Martindale and, Newton says, “they’re still very, very dear friends of mine.”)

Newton assembled the tribute, writing, directing, producing and starring in a play/concert hybrid in the theater Presley called home. He was backed by 35 musicians and seven singers. Former collaborators J.D. Sumner and the Sweet Inspirations were there. Comic Jackie Kahane, Presley’s longtime opening act, did a 20-minute set.

“He treated me, I think, like he probably treated Elvis,” Newton says of Parker during that time, “and that is, ‘Don’t ask me questions about that. That’s not what I do.’ ” That was in response to a query about a song choice. “He looked at me and said, ‘Wayne, go ahead and make the decision. I didn’t tell Elvis what to do onstage, and he didn’t tell me what to do in business.’ ”

That, Newton says, was the key to their success.

“They had a tremendous respect and love for each other, but both of them stayed out of each other’s way.”

Glimpse behind the curtain

With nothing left to promote, Parker kept a relatively low profile in Las Vegas, mostly only resurfacing to honor his late business partner.

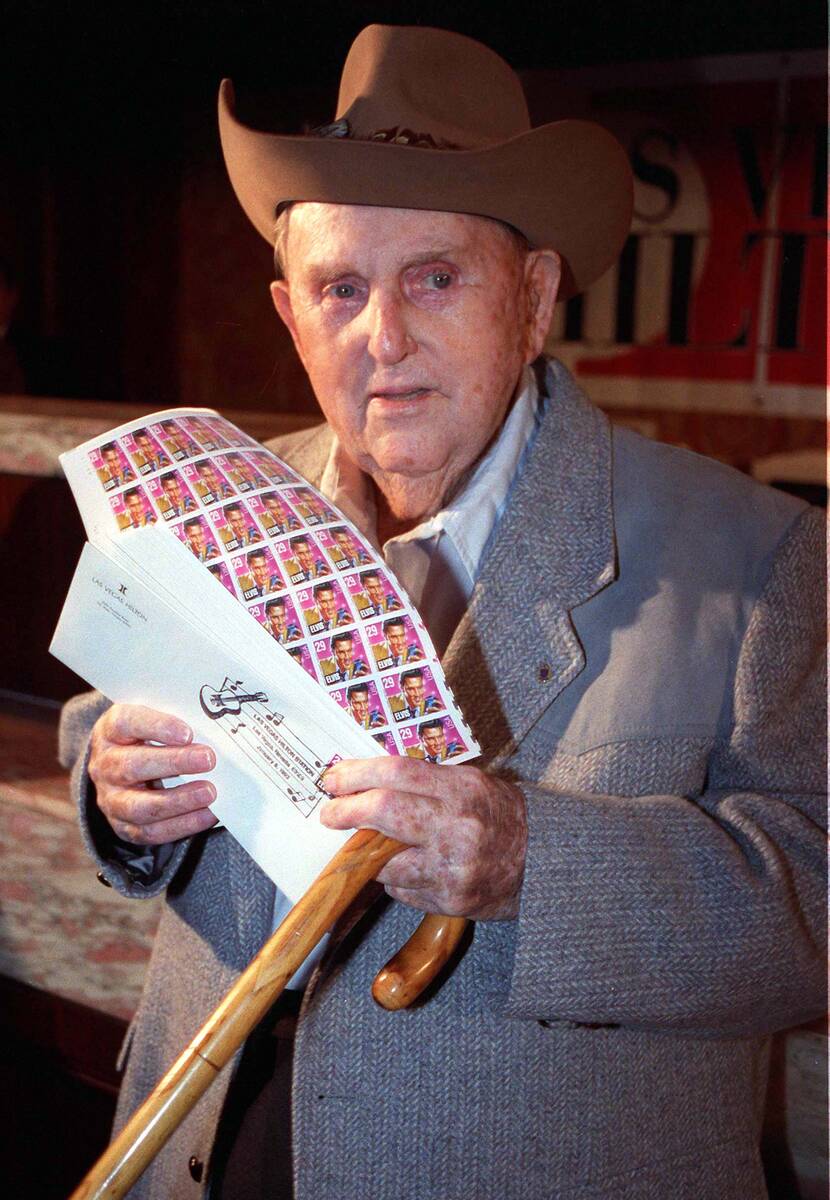

On Jan. 8, 1993, which would have been Presley’s 58th birthday, Parker bought the first set of Elvis postage stamps during a ceremony at the Hilton, then spent the next few hours signing autographs.

One of those was for a self-described psychic who said she’d been channeling Presley for the past 15 years. The singer wanted him to know he liked the stamp, she said, and he’d passed along a message: “For the very first time, I feel like a king.”

With interactions like that, it’s easy to see why he preferred to stay out of the spotlight.

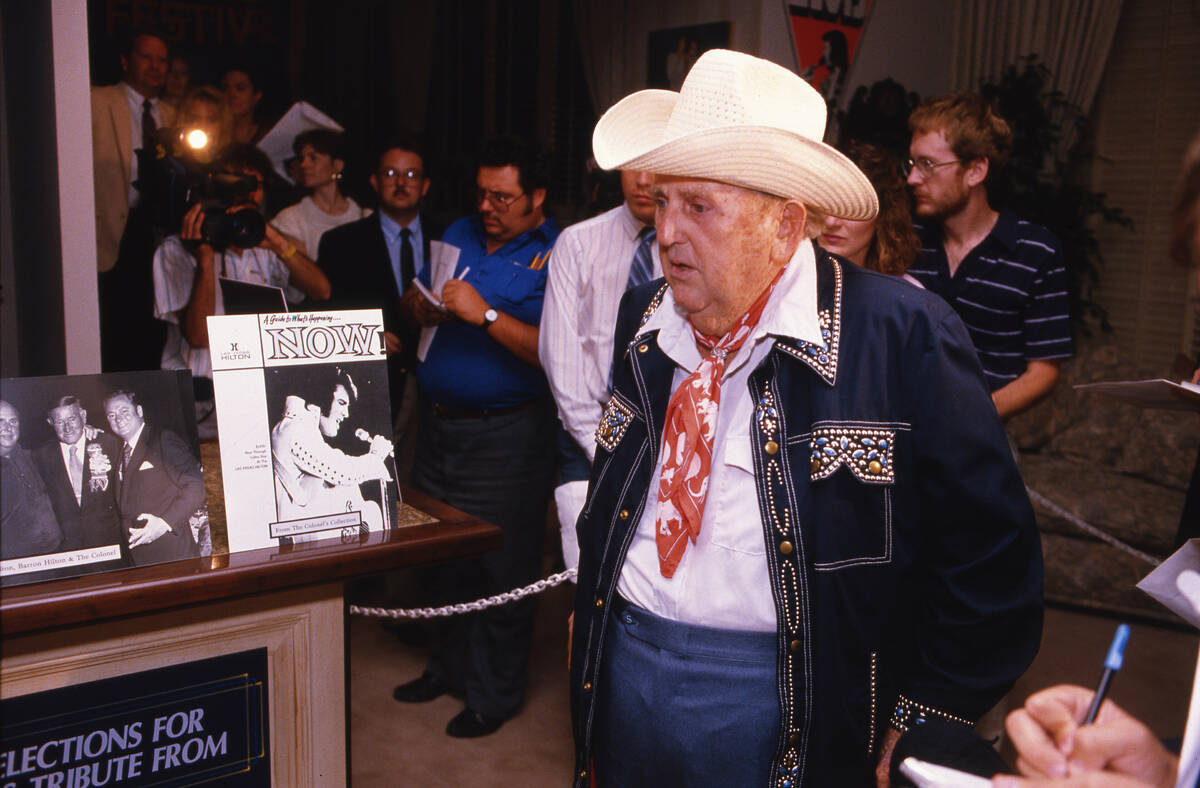

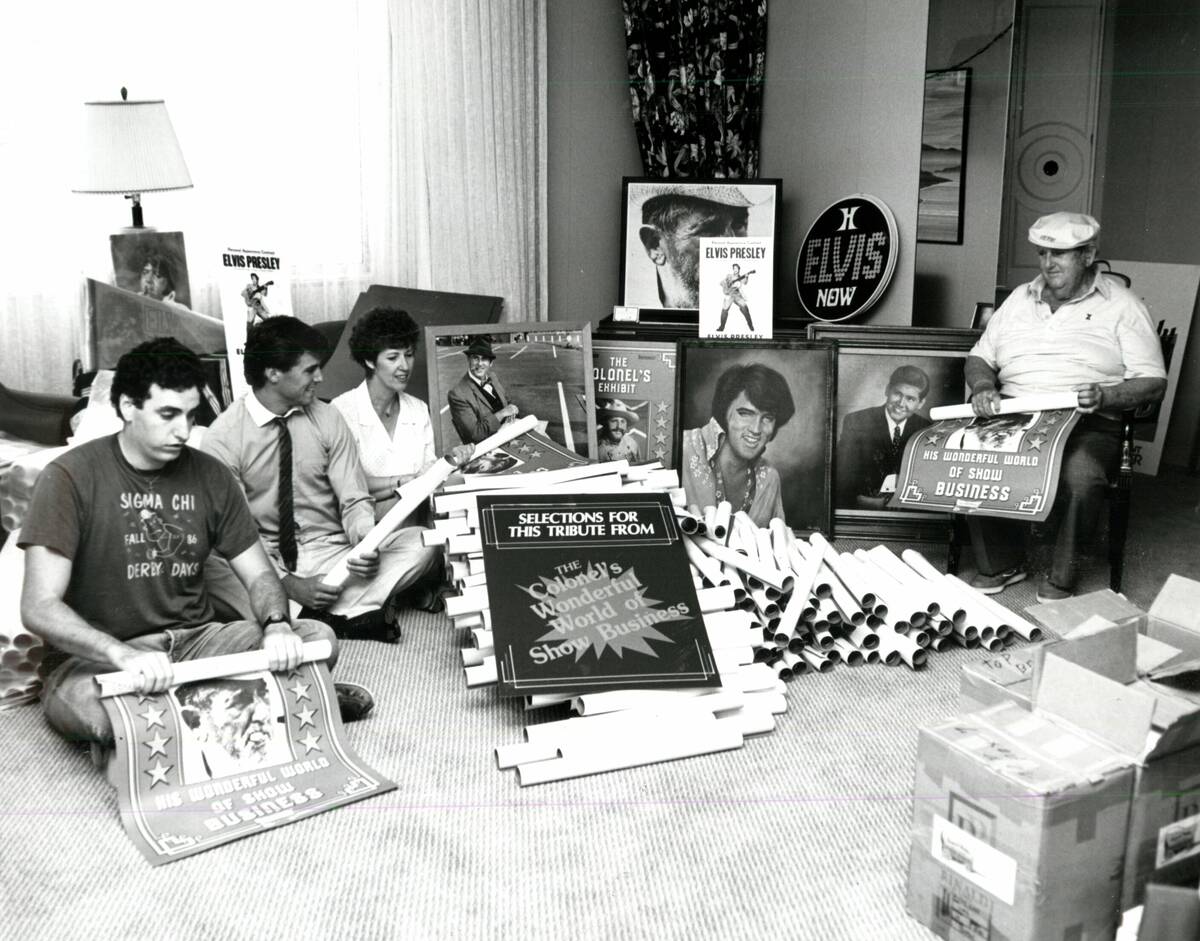

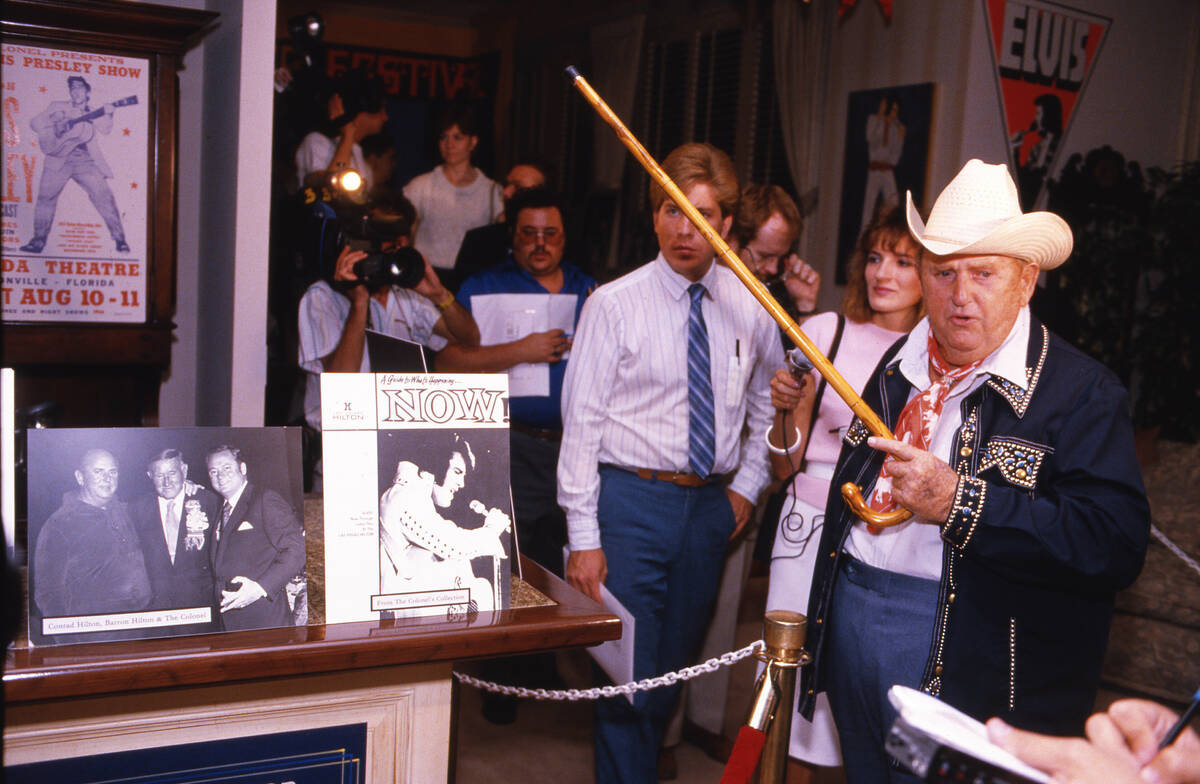

In conjunction with Newton’s tribute shows, the Hilton opened the 30th floor “Elvis suite” to the public. For $5, fans could take a tour, led by Parker, of the rooms Presley called home whenever he played the hotel. They’d been stuffed to overflowing with some of Parker’s keepsakes and memorabilia.

During a news conference and preview, Parker went out of his way to point out that none of the items was for sale and that he wasn’t interested in capitalizing on the event.

This, however, is where his legendary craftiness likely came into play. Parker also touted a museum he said he was planning to open in Tennessee that would display the rest of his memorabilia.

Some of those who knew him doubted he ever really planned such a thing and that, in reality, he was publicly angling for a better deal from Elvis Presley Enterprises and Graceland, its 5-year-old attraction that didn’t need the competition. Later that year, Parker sold those items — a reported 35 tons of memories including photographs, letters, recordings and that iconic gold lamé suit — to the singer’s estate for $2 million.

The deal also helped ease him back into the good graces of Elvis Presley Enterprises, and some fans, following several years of exile, the result of legal battles over Parker’s alleged financial mismanagement that only came to light after the singer’s death.

Charitable work

Despite his (likely earned) reputation as a taker, Parker began giving back to Las Vegas in 1956, during Presley’s first Las Vegas residency.

The two-week run at the New Frontier in front of a mostly older audience was shaking the young singer’s confidence, so Parker set up a weekend matinee show for his shrieking teenage fan base. Proceeds went to the Municipal Baseball Federation and toward the construction of the $35,000 lighted field, only the second in Las Vegas at the time, at what is now Ed Fountain Park.

Presley wouldn’t play Las Vegas again until that International/Hilton run that began in 1969.

Each time the duo would come to town, they’d donate merchandise for a souvenir booth in the hotel lobby, let a different organization staff it with volunteers for as many as 18 hours each day, then allow them to keep the money. The only requirement was that none of it could go toward salaries or expenses.

“It is like a dream come true,” Cleo Harmon, president of the newly formed Girls Club of Southern Nevada, told the Review-Journal following Presley’s shows in the fall of 1973, during which the group earned $32,593. “Through the generosity of Elvis and the Colonel we collected in just four weeks what it would have taken us at least five years to raise.”

Jerry E. Polis, past president of the Nevada Society for the Aurally Handicapped, wrote a letter to the editor in 1975 to “publicly thank Col. Tom Parker and Elvis for their outstanding generosity in our community.” Through their partnerships, he wrote, more than $45,000 had been spent on classroom equipment for the valley’s deaf children.

Over the years, Presley’s Nevada shows raised more than $250,000 this way.

Lasting relationships

Philanthropy didn’t always follow a traditional path with Parker.

Take the time four peregrine falcons were released at the Flamingo Hilton in 1991 as part of a project to re-establish the endangered birds in the valley. Parker pledged to pay for their diet of dead quail and pigeons.

During an early tour of Opportunity Village, he “fell in love with the organization and what we could do,” says Tracy Brown-May, the group’s chief administrative officer. Parker would return in later years, dressed as Santa Claus, and distribute stuffed hound dog toys.

He also made certain that all those scarves Presley wore onstage, some just long enough to get slathered in his DNA before he whipped them into the frenzied crowds, were made by the people with intellectual disabilities being served by Opportunity Village.

“When you have been told your whole life, ‘You’re insignificant; you’re not equal; you’ll never measure up.’ And you come and learn this skill … and you’re making a scarf for Elvis? That’s phenomenal,” Brown-May says.

The scarf-making business continues to this day, with the artists who create them earning the pride of employment as well as half the sale price.

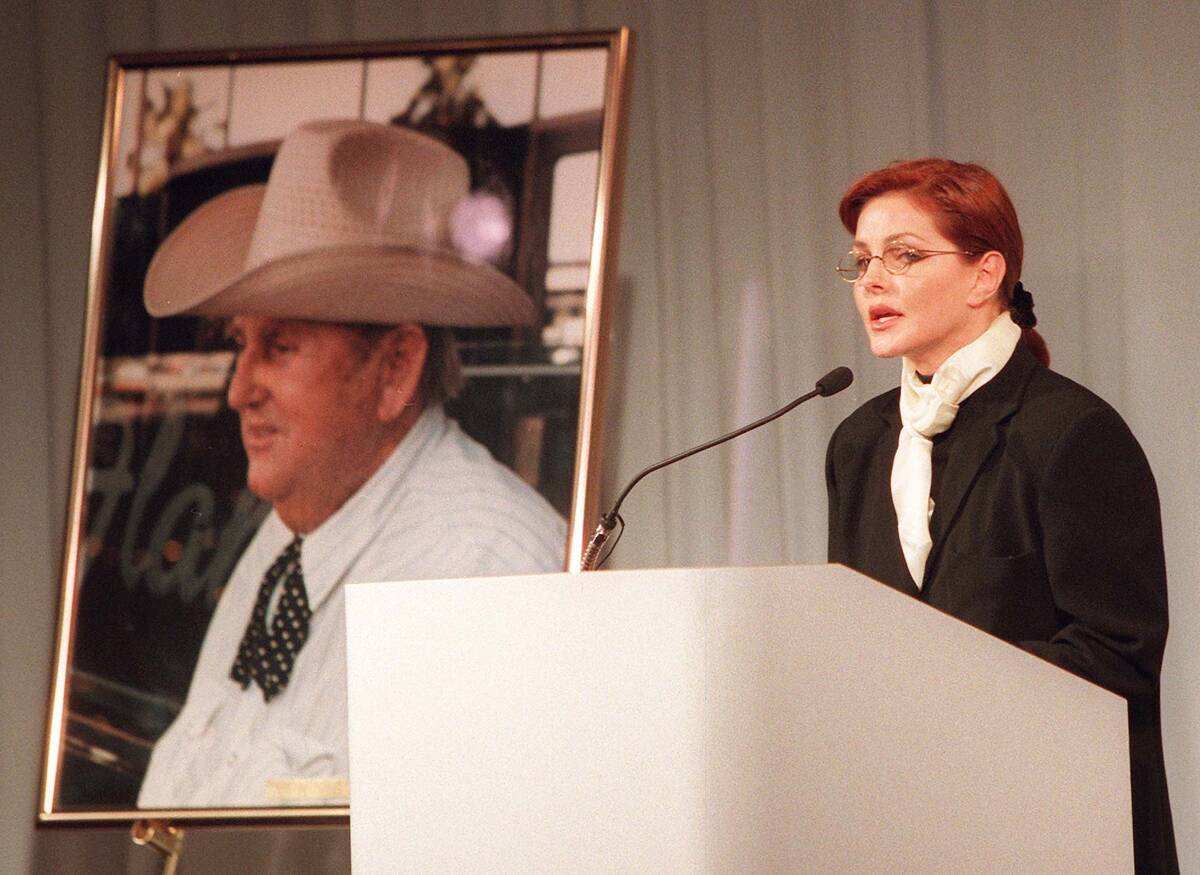

Then there was Parker’s long-standing association with a fund through which he’d channel money from those rare personal appearances to send hundreds of local children to camp. Following his death on Jan. 21, 1997, at Valley Hospital from complications of a stroke, Parker’s obituary asked that all memorial donations be sent there.

Parker’s own words

In her book “The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley,” Alanna Nash describes Parker’s later years. He’d kept a suite of rooms and offices on the fourth floor of the Hilton from 1969 to 1984. The following year, he moved to Las Vegas full time, taking a unit in the nearby Country Club Towers. By 1989, he and his second wife, Loanne, had purchased a townhouse in the Spanish Oaks area.

“They lived simply,” Nash wrote, “shopping at Von’s grocery at Decatur and Sahara, where Parker often waited outside on a bench and talked to passers-by while Loanne did the marketing. She bought his clothes off the rack at JC Penney.”

Out of the hundreds of mentions and stories about Parker, the Review-Journal archives contain exactly one interview with the man.

For a story published Jan. 8, 1995, on what would have been Presley’s 60th birthday, Parker looked back on the icon and the intense fandom he inspired.

“A lot of these fans, they’ve grown up with Elvis and they have a certain companionship when they meet with other fans,” he said. “So maybe some of these people are lonely (and) they feel like they belong together, just like a flock of sheep. … They find someone like Elvis and they believe in that. We’re not here to question that.”

When he was approached by just such a group of fans, who told him they kept in touch with Presley through weekly seances, Parker replied, “Here’s my new number. The next time Elvis shows up, give it to him and have him call me.”

In that same interview, the 85-year-old Parker admitted to the occasional bout of sentimentality.

“Every once in a while, I sit by myself in my old rocking chair and talk to myself about Elvis. We had a communication. Some of the best deals we made were when we argued together (because) we came up with a better solution.”

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567. Follow @life_onthecouch on Twitter.