Is Las Vegas about to become an art mecca? Ralph DeLuca thinks so.

From a home as vintage as the silk robe he’s just doffed, Ralph DeLuca is talking about the time he dropped over 300 grand on a movie poster.

“People thought I was crazy,” he recalls through a brick-thick New Jersey accent.

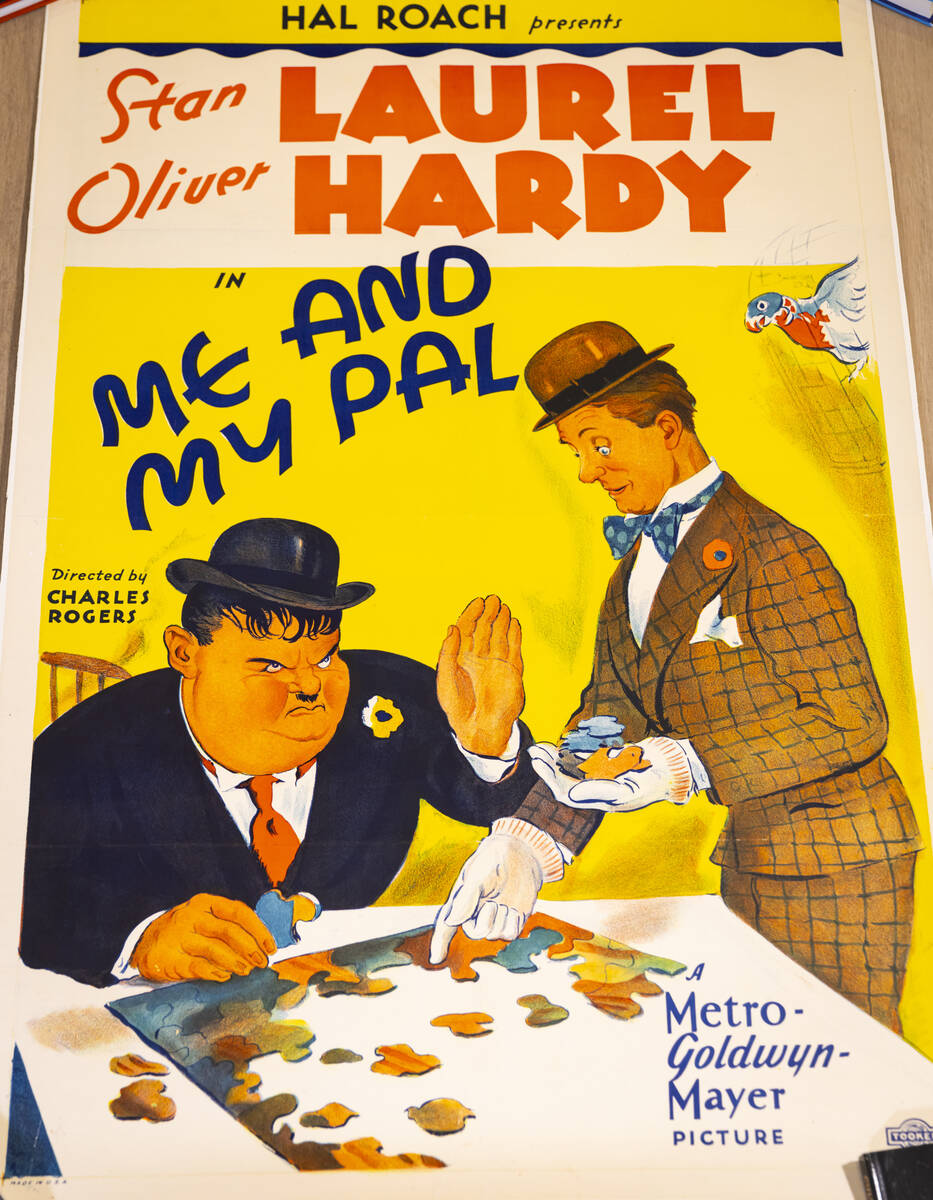

Flash back to April 2009: DeLuca has just bought an original poster for the 1931 horror classic “Dracula,” once owned by actor Nicolas Cage, for a then-record $310,000.

Former investment banker DeLuca’s Wall Street buddies were raking it in while he was spending six figures on film ephemera.

“I remember friends and they were like, ‘Oh, we’re making all this money,’ ” he recalls. “They had Enron or Lehman Brothers (stock), and I was buying ‘Dracula’ and ‘Frankenstein’ (posters).

“They have nothing to show for it,” he continues, possessing the aura of a meat cleaver swathed in satin: blunt but with the distinct air of the refined. “None of this stuff will ever Enron: It’ll never go to zero.”

DeLuca has been proven right thus far: In 2017, one of the few remaining “Dracula” posters was auctioned for over $525,000.

His sharp eye for art of all stripes — and an intense passion for collecting — has made him an increasingly prominent figure in the art world, despite his unlikely pedigree as a self-taught, self-made son of a longshoreman.

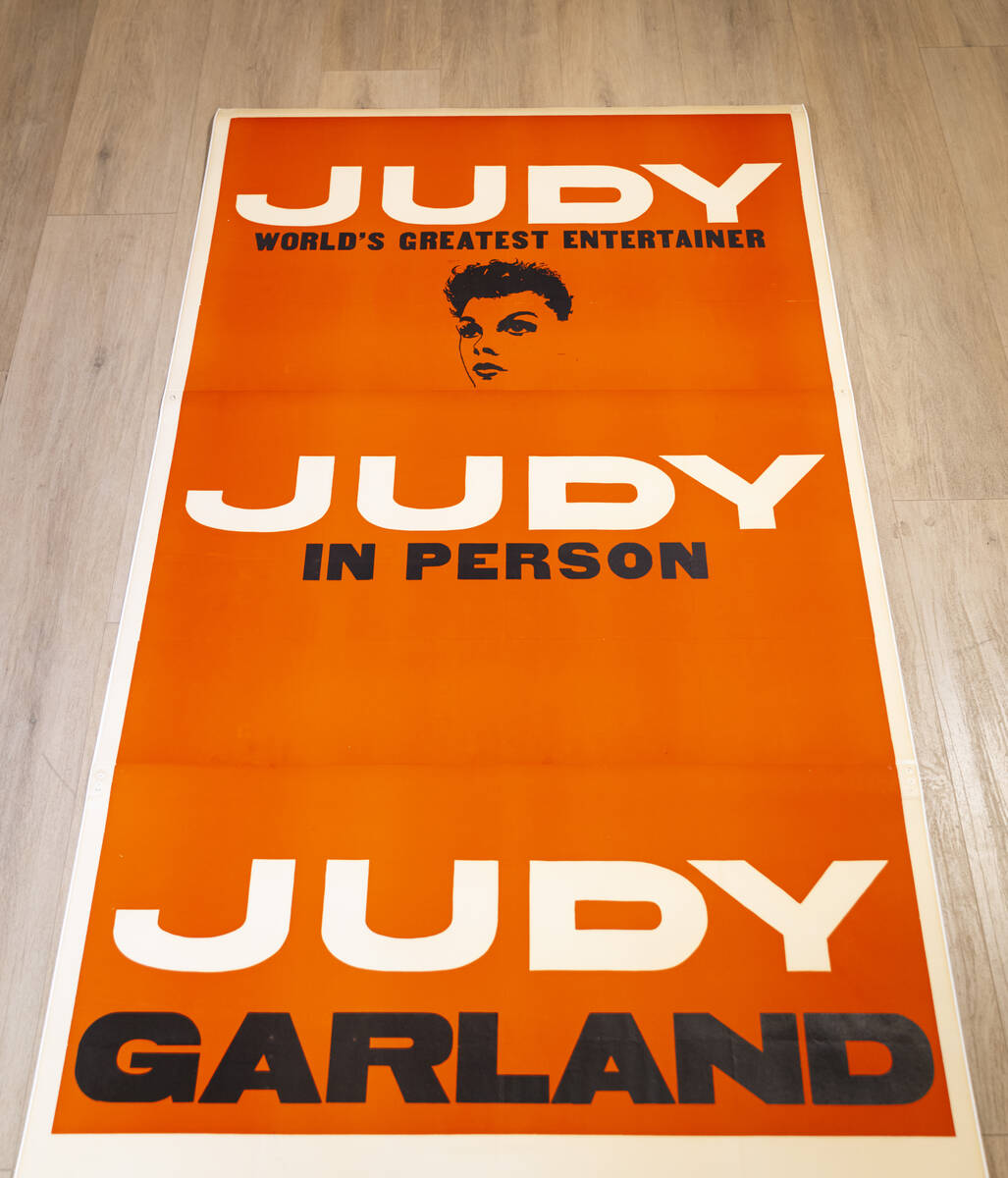

He still collects posters — DeLuca has over 5,000 of them — and photographs (more than 20,000, including a selection of works from iconic photographer Diane Arbus) as well as casino chips, old records and — why not? — even vintage cereal boxes.

But DeLuca also collects art — he owns 1,000-plus paintings, including plenty from major figures such as Andy Warhol and George Condo — and has made a name for himself by helping others do the same.

Over the past decade, DeLuca has branched out from poster expert to renowned art adviser whose celebrity clients include box-office breadwinners Leonardo DiCaprio and Sylvester Stallone.

He works with distinguished galleries such as David Zwirner in New York City and Hauser & Wirth in Los Angeles. In June, DeLuca was named one of Cultured Magazine’s top 20 art advisers for 2024.

Locally, he advises the MGM Grand and curated the “Icons of Contemporary Art” exhibit at the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art. He has helped the company acquire works from such notable artists as Ghada Amer, Tomás Esson, Rashid Johnson, Sanford Biggers, Svenja Deininger and Derrick Adams.

“Ralph is an insightful partner with a keen eye, and has been invaluable in helping us collect an array of both midcareer and established artists,” says Ari Kastrati, MGM Resorts International’s chief content, hospitality and development officer. “As both an art adviser and avid collector, Ralph brings valuable connections with notable galleries and artists from around the world.”

So, how did this Jersey boy who once worked as an insurance salesman get the attention of the A-list actors and Fortune 500 companies who seek his help curating their collections?

An even bigger question: How did he end up in Vegas — where he’s had a home since 2017 — a city hardly known as an art mecca in the past?

Because DeLuca has become adept at seeing in advance where the art world is headed.

And he believes it’s headed here — with a little help from an East Coast transplant whose words tend to be delivered with the speed and precision of a boxer’s fists.

“There is this network of people there that have a long history of patronage of the arts, but that history is not one that has been widely written about or is really in the consciousness of the art world in New York,” says Alex Shulan, owner and curator of New York City’s Lomex Gallery, reflecting on the industry’s perception of Las Vegas, which he has visited with DeLuca.

“When I’ve talked to some other people about my interest in Vegas, or the time that I spent there with Ralph, they’re surprised, because it’s not something they traditionally associate with patronage of the arts.” he continues. “I think Ralph is really on a personal mission to change that.”

‘I want to be in the history of Las Vegas’

We first meet DeLuca in a private room at the Mob Museum, which he inhabits as naturally as a fish does water — or, perhaps a more fitting comparison considering the surroundings, a slain gangster awash in the depths of Lake Mead.

DeLuca is an inner-circle member here and sits on the museum’s advisory council.

He has also contributed to its collection: DeLuca located the original contract Bugsy Siegel signed to purchase the Flamingo and donated a considerable sum to help secure it for the nonprofit.

DeLuca has been coming to Vegas since he was a boy: He remembers family trips to Caesars Palace and being awed by the spectacle of it all — the buffets, the pools, the shows.

This was the ’80s, the waning days of the mob’s influence on Vegas, a time period that DeLuca has a particular affinity for.

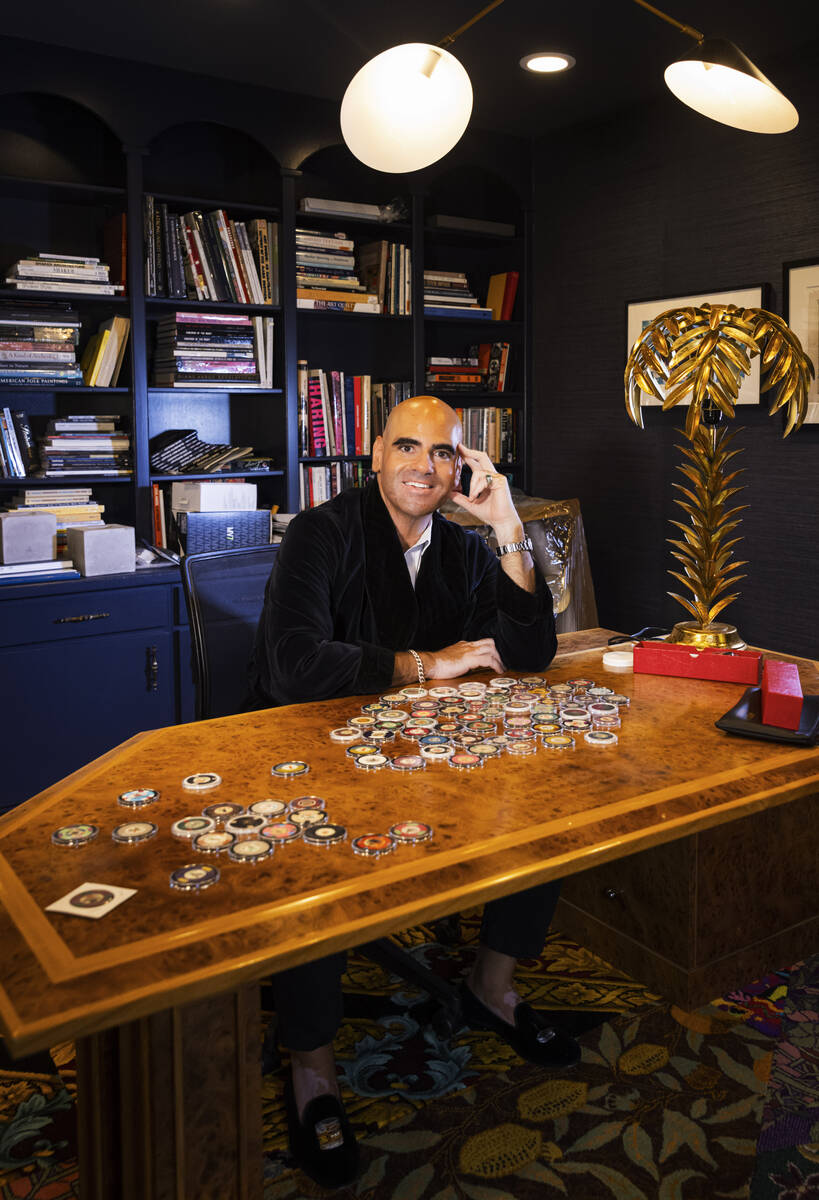

To wit, a few weeks later, when we visit DeLuca’s home and he shows us his impressive collection of vintage casino chips, some of which are worth thousands — among them, a rare “blood spatter” chip from Club Bingo, nicknamed after a production error resulting in an excess of red dye — he’s quick to point out they’re all culled from a specific age.

“I only collect mob-era Vegas, ’30s to 1989,” he notes from his office, chips spread out on his desk. “When the mob left, I stopped collecting.”

How did DeLuca find his first Vegas house seven years ago?

By calling up Martin Scorsese and asking the iconic director where he filmed the residential scenes in his gangster classic “Casino.”

Turns out it was Paradise Palms, where DeLuca bought screen legend Betty Grable’s old house.

He’s since moved to a high-ceilinged home in the equally old-school Scotch 80s neighborhood, originally built by casino mogul Bill Boyd.

“I want to be in the history of Las Vegas,” he explains. “I want to live like a retired mob boss in my house and walk around in a cool bathrobe, go in my pool and have all my collectibles. I need the culture.”

DeLuca is redecorating the property with a Hollywood Regency aesthetic, all throwback glitz and glamour — one room comes swathed in the Beverly Hills Hotel’s signature green banana leaf wallpaper — with numerous nods to vintage Vegas, from a repurposed Golden Nugget slot machine near the front door to a rug fashioned out of a pastiche of casino carpets in his office.

One hallway is lined with a DeLuca favorite: dozens of black velvet portraits of curvaceous women in various states of undress, some done by Cecilia “CeeCee” Rodriguez, a Vegas artist who lived to be over 100.

It’s a fitting visual metaphor for the city in which DeLuca now resides: He likens Las Vegas to a velvet painting, often dismissed as low-brow by the high-minded, lacking in culture, abundant in kitsch but whose ostentatious surface doesn’t tell the whole story.

But DeLuca is fond of digging deep into what others may find shallow. He favors an egalitarian perspective in an industry that has long been stratified among mediums. He’s become an art world insider, but he still carries himself more like an outsider — and serves as a bridge between both.

He’s the kind of guy who can speak eloquently and at length about the early 2oth-century Russian constructivism movement in one breath and the legacy of cultural inclusivity inherent in a half-naked lady painted on dark fabrics in the next.

“I think it’s all art,” he shrugs.

This includes Las Vegas.

The lifelong collector

With a grin, DeLuca remembers his father’s reaction after his young son purchased his first piece of art, a Salvador Dali lithograph he bought with his birthday money upon turning 13.

Dad was less than impressed.

“I remember bringing it home all excited. It was like 400 bucks. Still have it to this day,” DeLuca recalls. “My father looked at me and he was like, ‘What the (expletive) is wrong with you?’ I was like, ‘I don’t know what the (expletive) is wrong with me. I like it.’ So that started me on art and a visual language. Ever since then, I’ve been a lifelong collector.”

After graduating from high school, DeLuca went straight to Wall Street, where the preternaturally energetic talker put his verbal skills to use.

“I was really good at trading stocks; I was great on the phone and raising money for public and private companies,” he says. “When I started making more money, I started collecting more.”

DeLuca got burned out and left the investment industry in the late ’90s, selling life insurance to make ends meet while collecting on the side.

“I just remember one month, maybe I made eight or 10 grand, and I think I made, like, five times that buying and selling movie posters,” DeLuca says. “I just used whatever knowledge I had about marketing and financial markets to start looking for movie posters, building a collection, building a clientele, and then it took off from there.”

DeLuca became obsessed.

“I really just had blinders on,” he says. “I would study it all day. I memorized old auction catalogs. I’d get old price guides. I bought 20 years of the back issues of all the trade papers for people in the Hollywood poster collecting and movie memorabilia avenues. I’d call every dealer, bid in every auction, search all over.

“I would travel the country way before the show ‘American Pickers,’ ” he continues. “I would take ads in 400 or 500 local papers, looking for posters and going to make appointments and getting in people’s houses or having them come to my hotel room and stuff.”

In addition to posters, DeLuca began dipping his toes into the art world, hiring an art adviser whom he worked with for over a decade, introducing DeLuca to these ever-exclusive circles.

“I started focusing on paintings, and I was learning that field,” he says. “Little did I know at the time, I was getting groomed to be an adviser.”

A high barrier to entry

Here’s the thing about buying of-the-moment modern art: Most of us can’t.

And it’s not a money thing, either: It doesn’t matter if you’ve got the dough if you don’t have the entree to spend it.

This is where DeLuca comes in.

“The barrier to entry in the contemporary art world is really hard,” he explains. “It’s the only business I know where you walk into a gallery, you say, ‘How much is this?’ And they’ll say, ‘Who are you?’

“The things aren’t really for sale to the general public,” he continues, explaining his role as an art adviser. “You have to almost be like a steward — especially with emerging art from living artists. Anyone can go to an auction and buy a painting or from some secondary market dealers, but if you’re dealing with a living artist, primary market works — meaning you’re the first person to actually own the painting when the artist consigned it to his gallery — there is definitely a barrier to entry to get access.”

Access is what DeLuca trades in.

He cultivates it by operating in a manner similar to a Hollywood agent pitching his clients to movie studios and casting directors, albeit to galleries and artists instead, both of whom often pay close attention to the motivations of their prospective buyers.

They have to: As in the film business, reputations are on the line here.

“They want to make sure you’re not just collecting for the money, because a lot of times when you’re buying stuff in the primary market, there’s a significant instant upside,” DeLuca explains. “There’s people that are called ‘flippers’ that’ll sell a painting they bought for $25,000 at auction. It goes for $100,000, $200,000 in some cases, and they want to make sure that doesn’t happen, because it doesn’t help the artist — the artist doesn’t get any of that money. It only brings speculators in, as opposed to people who really want to be tastemakers and curate the works into their collections and donate to public institutions.”

DeLuca has earned trust in the industry in large part by not carrying himself like a traditional art adviser.

“He has a very different perspective than a lot of other art advisers, where he’s also interested in communicating with different audiences than the art world has historically limited itself to,” Shulan explains. “He’s quite a straight shooter. He’s super-candid about his feelings and his opinions about the things that he’s looking at, and also has a way of talking to people that I think is super-relatable and more accessible.

“He’s also really acting as an educator,” he continues. “Ideally, that’s what an art adviser is supposed to do, is be someone who not only helps you pick what kind of art you want to acquire, but also teaches you about art history and about the dynamics of the art world, introduces you to new artists that you don’t know about.”

It’s these artists in particular, emerging talents, who have helped DeLuca make his name.

An eye for emerging artists

Gazing up at a wall in his home, DeLuca eyes a portrait of an African American woman, fingers gripping a cigarette and a gleaming cross necklace in unison, done by artist Danielle Mckinney.

“When I bought this painting, I think I paid $12,000 or $13,000,” he notes. “They sell for a quarter of a million now.”

Nearby hangs a Picasso-like painting from Louis Fratino.

“I think I paid $8,000 for this,” DeLuca says, noting he was offered much more to sell it years later. “I turned down $250,000.”

And then there’s a gorgeous piece alive with golden spirals from artist Julie Curtiss that Deluca purchased for around $10,000 at New York City’s Anton Kern Gallery back in the day.

It’s now worth more than 20 times that, he estimates.

One of the keys to DeLuca’s success is being ahead of the curve on the up-and-coming artists of today who just might blossom into the stars of tomorrow.

“I like to support the artists and grow with them,” he says. “And I think you can actually build serious collections — both of importance and value — collecting young artists, supporting them and owning it, because you look at a lot of the old collectors, they bought Warhol, Basquiat, Keith Haring while they were alive.

“The really major collectors are not the billionaires who just came in,” he continues, “although it’s getting less and less connoisseurship and more, ‘Oh, I paid $100 million for this Basquiat.’ What I find more interesting is the person who paid $1,800 for their Basquiat or $18,000.”

Of course, there are risks.

“A young artist, five years from now, could say, ‘I have kids. I want to be a writer only and not create paintings,’ and then maybe there’s no market,” he says. “That happens. There was some young artist that became a DJ, doesn’t create art anymore. But, overall, I choose right well more than I choose wrong.”

The art world comes to Vegas

“Look at this house!” DeLuca exclaims, cellphone in hand, eyes nearly as wide as its screen. “This is the house I was trying to buy.”

DeLuca is showing us pictures of a decades-old Vegas home he’s been attempting to acquire, marveling at its vintage decor, velvet wallpaper all.

“Isn’t that cool? All from the ’60s,” he gushes. “I want to preserve this house.”

He also wants to host out-of-town artists where they can both create and share their works.

“The whole theme is: the hottest galleries in New York opened up in a secret time capsule in Las Vegas,” he explains, “and you don’t know where it is. And you’re not invited. Just have cool people come.”

DeLuca has long been bullish on recruiting the art establishment to town.

“I’ve met with some people who want to have an art fair here,” he says. “I’ve met with some very serious galleries that want to come here and open gallery spaces. Emerging artists — all the artists — love being here.

“I’m bringing dealers who are looking to do pop-up spaces,” he continues, “and talking to galleries, talking to the collectors and the tastemakers and the real estate owners in this city about how to embrace the international and the New York, L.A. art world in Vegas.”

To underscore his point about the momentum Vegas been gaining in art circles in recent years, DeLuca cites Sotheby’s auction of 11 Picasso pieces culled from MGM Resorts’ collection at Bellagio in October 2021, when $109 million worth of art was sold in 45 suspense-filled minutes.

“For the first time you saw eight-figure artwork being sold in Las Vegas that was from a Las Vegas casino collection that brought in the whole art world,” he says. “There were people all over the world that came in for that — celebrities, major dealers, major collectors. It was great.”

In an even bigger development of late, plans were recently announced for Vegas’ first major art museum, something the city has glaringly lacked as its population has climbed, making it the only top 30 market in the country without one.

Spearheaded by Elaine Wynn and renowned interior designer Roger Thomas, the new 90,000-square-foot space is expected to open downtown in Symphony Park by the end of 2028 at a projected cost of $150 million.

The museum’s executive director is Heather Harmon, a friend of DeLuca.

“I think that Las Vegas is so fortunate to be home to an art adviser of Ralph’s caliber,” Harmon says. “His thoughtful rigor brings great depth to his work. I mean, he’s impressively self-taught, and his art historical knowledge is extensive. I know he’ll have a great impact on the cultural landscapes in Las Vegas.”

In the meantime, DeLuca continues serving as an unofficial ambassador for the Vegas art community, bringing in industry notables like Shuman to visit, taking him to all his favorite haunts downtown.

And about that second house DeLuca has been after and the future artist’s lair he envisions: His Realtor found the listing for the property at 7 one morning. DeLuca was there by 8:15 a.m., bidding on the place, but losing out to a flipper.

Not one to settle, DeLuca tracked down the buyer and emailed him, making another offer that’d earn him a tidy profit.

The flipper was quick to respond.

“He goes, ‘I know who you are,’ ” DeLuca recalls. “ ‘You’re the art guy.’ ”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram