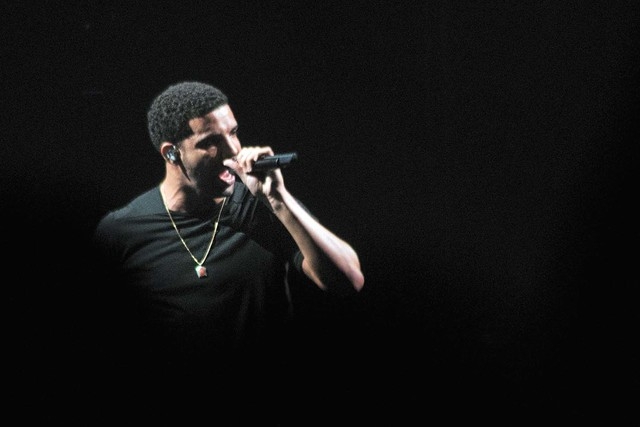

Hip-hop ham: Drake flaunts success, but then feels guilty

The words coming out of the man’s mouth and the shape of said mouth seemed opposed to one another.

The words: blustery, self-satisfied, suggestive of the tight-lipped, look-at-what-I-have-and-you-don’t smirk of a dude with a sports car snickering at your Dodge Neon.

The mouth: wide open, a toothy wedge of happy-go-lucky good will, the kind of warm grin that not only invites you to the party, but offers to pour you your first drink.

“I got everything!” Drake proclaimed through the aforementioned smile the last time he performed in Las Vegas at the iHeartRadio Music Festival in September, his brief set a welcome burst of energy and charisma.

This is one of Drake’s greatest skills: making you like him even when he says intensely unlikable things.

The song in question was “All Me,” a tune about Drake pulling himself up by his bootstraps and then strangling the competition with them.

“Should I listen to everybody or myself?” he said aloud. “ ’Cause myself just told myself, ‘You the (expletive) man, you don’t need no help.’ ”

Such bravado is not uncommon in hip-hop.

Mostly, it’s as expected as a wide receiver’s posttouchdown end zone dance, and it’s similarly anti-climactic: What really thrills us, in both cases, is how he got there, the plays he made, not the celebration afterward.

This is the challenge that Drake wrangles with on his latest disc, the equally absorbing and obnoxious “Nothing Was the Same”: How does he revel in his success without becoming dulled by it?

How does he maintain his hunger with a belly full of caviar and Champagne?

Dreams are great and all — until they come true.

Then what?

“My life’s a completed checklist,” Drake boasts over a sped-up vocal sample suggestive of an imperiled chipmunk on “Tuscan Leather,” which opens “Nothing Was the Same.”

But here, and in numerous other places, Drake builds himself up to tear himself down.

“I’m honest, I make mistakes, I’d be the second to admit it,” he acknowledges on the same track, reaffirming his place as hip-hop’s pre-eminent self-scrutinizing braggart.

Often times, overconfidence is a defense mechanism, a way to insulate yourself from your shortcomings by exaggerating your strengths.

Now, Drake’s as cocksure as they come — “I’m about as big as it gets,” he notes on “All Me,” channeling his inner Ron Burgundy — but he acknowledges his weaknesses just as readily as he does all the zeroes in his net worth.

He womanizes, but then feels guilty about it.

“I was young and I was selfish,” he tells a former flame on “Furthest Thing,” at least attempting to explain his philandering ways. “I made every woman feel like she was mine and no one else’s.”

He gloats about his conspicuous consumption, about blowing money on cars with six-figure price tags and flying women first class to meet up with him while he’s on tour, but then seems to have second thoughts about the example he’s setting.

“Tryin’ to get my karma up, (forget) the guilty and greedy (stuff),” he announces on “Tuscan Leather,” suggesting that his emphasis on materialism may not be terribly edifying.

But here’s the thing: Drake still bed hops, still flaunts his riches with palpable relish.

In other words, he doesn’t have things figured out just yet, and he wears this ambivalence like he does the gold chains around his neck: for all to see.

This inner conflict, this uncertainty, is what makes Drake more relatable than mentors like Lil Wayne and Jay-Z, who have their faults like everybody else, but who mostly confine acknowledgments of vulnerability to when they’re speaking of the competition.

This openness has gone a long way in making Drake a superstar, elevating him to the genre’s leading man of the moment, which he cemented with “Nothing Was the Same,” which sold 660,000 copies its first week of release in September.

Of course, it’s not just what Drake says that’s made him an arena headliner, but how he says it: His delivery is as smooth and polished as the grill of the Bugatti he brags about buying on “Pound Cake/Paris Morton 2,” abetted by a modest singing ability that he judiciously employs to add touches of melody to his often minimally produced songs, where the beats and any instrumental flourishes haunt tracks rather than power them and any bombast is largely confined to the lyrics.

Like Kanye West, whom Drake has succeeded as hip-hop’s reigning prodigal son, Drake has a conscience that nags at him, steps on his shoelaces as he’s racing off to the next party.

When he stumbles, he identifies with those who’ve done the same, like his uncle, who, in the song “Too Much,” has given up on his life’s dreams and become resigned to never achieving them.

“Listen, man, you can still do what you wanna do,” his nephew urges him.

But it’s not so easy.

After all, he’s not Drake.

Contact reporter Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow on Twitter @JasonBracelin.

Preview

Drake

8 p.m. Friday

MGM Grand Garden arena, 3799 Las Vegas Blvd. South

$68.85-$123.20 (800-745-3000)