Lost City Museum holds artifacts of native cultures

A treasury of artifacts from ancient Native American cultures awaits visitors to the Lost City Museum in Overton.

The museum, built on the site of an Anasazi village abandoned centuries ago, provides an introduction to thousands of years of cultural heritage that developed in a verdant valley along the Muddy River. The area was inhabited by a succession of native people, including the Anasazi, who farmed there centuries before the Mormons arrived in the 1800s.

To reach the museum, drive north on Interstate 15 from Las Vegas for about 55 miles. Just past Glendale, exit onto state Route 169, the road that parallels the river as it runs through the rural towns of Logandale and Overton. A short spur road leads to the museum, which sits on a bluff near the highway about 12 miles from the I-15 exit.

The Lost City Museum began in 1935 with the construction of a single-story adobe by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The building, at first called the Boulder Dam Museum, housed artifacts unearthed by archeological work done in the valley ahead of the filling of Lake Mead. Eventually, the lake covered a few pioneer Mormon communities and inundated several miles of scattered pueblo ruins.

The existence of the ancient ruins was well-known to pioneers establishing farms and communities along the Muddy River above its confluence with the Colorado River. In the 1920s, local brothers John and Fay Perkins contacted Nevada’s governor about the ruins, since he was trying to develop tourism in the state.

Because of the plans for Hoover Dam and the lake, action needed to be taken to preserve the artifacts in the valley. A noted archaeologist performed the fieldwork and research. The Perkins brothers worked on early excavations and maintained a lifelong interest in the museum.

Today, visitors can see many artifacts from their private collections among the museum’s displays.

The original adobe, which was built upon a large ruin called Casa Grande de Nevada, is now nearly 80 years old and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The small structure still fulfills its purpose, but it has been enhanced by additions that include much more exhibit space, a gift shop, offices, storage and restrooms.

The museum is open from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m daily except Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Day. The entrance fee is $5 for visitors 18 and older who are not museum members.

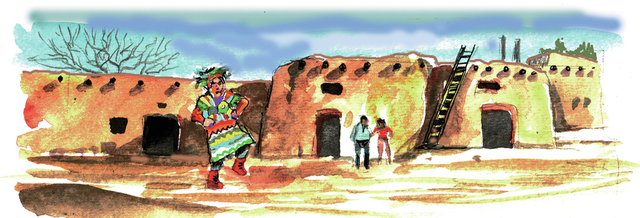

Outside the building, visitors will find paved parking, covered picnic pavilions and landscaping that features native plants and trees. Walkways lead to reconstructed pueblo-style dwellings and excavated ruins, including a pit house that was probably used for gatherings and ceremonies. Visitors get a glimpse of what life was like for those early native families, when as many as 10,000 people inhabited several villages throughout the valley.

The earliest native people followed game into the river valley about 10,000 years ago. These hunter-gatherers left little sign of their presence there, except for a few seasonal campsites, stone arrowheads and spearheads and simple tools.

Later nomads augmented their hunting and gathering with small plots of corn, squash, beans and cotton planted near the river. Over time, they devised irrigation methods to improve crop yields.

As they became better farmers, they began to spend more time in the area and built permament homes. This group was the westernmost outpost of a widespread culture known as the Ancestral Puebloans, of Anasazi, that reached across Arizona from the Four Corners area.

By about A.D. 1150, people across the region had abandoned their farms and villages. Although many theories have been formulated, the reason for their disappearance remains a mystery.

Margo Bartlett Pesek’s column appears on Sundays.